Does ADHD Exist?

In the year 2000, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) released a consensus statement concerning the diagnosis and treatment of ADHD (National Institutes of Health, 2000) and indicated that “despite the progress in assessment, diagnosis and treatment of children and adults with ADHD, the disorder has remained controversial.... The controversy raises questions concerning the literal existence of the disorder” (p. 182). This concern mirrors the views expressed by others such as Armstrong (1995), who has questioned the authenticity of ADHD, and Baughman (2004), a neurologist, who is the author of a video entitled “ADHD—Total 100% Fraud.” Although the concern may be well intended, research across behavioral, genetic, neuropsychological, and neuro-physiological disciplines supports the existence of ADHD; and a diagnosis of ADHD can be made reliably using various assessment methods discussed in later chapters. In fact, the NIH consensus statement after thorough review of the scientific evidence concludes that ADHD is a valid disorder and this perspective is endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Medical Association, the American Psychiatric Association, the American Psychological Association, the National Association of School Psychologists, the U.S. Surgeon General, and others. In 2002, a consortium of international scientists addressed the assertion that ADHD is a fraud by reviewing the scientific evidence to the contrary and issued the International Consensus Statement on ADHD (2002).

Admittedly, there is not an objective, conclusive “test” for the disorder, but nor is there an objective test for the common cold or many clinical conditions such as autistic disorder, depression, Tourette’s disorder, and obsessive compulsive disorder. Like the common cold, depression, and other disorders, a diagnosis of ADHD is based on the presence and severity of symptoms. In the case of ADHD, the symptoms have an early onset; are chronic, pervasive, and developmentally inappropriate; and cause significant impairment in an individual’s life.

ADHD is the most frequently studied disorder of childhood, and volumes of scientific evidence attest to the existence of the disorder (e.g., Asherson, 2004; Brown et al., 2005; Wolraich et al., 2005). To deny the existence of ADHD can do far more harm than good. Long-term studies, for example, have found that children, adolescents, and adults with ADHD—compared to those without the disorder—are at significantly greater risk for academic, behavioral, and social problems (see Developmental Information later in this chapter). Early identification and intervention are essential to improving the outcome of individuals with the disorder, and educators often play a key part in both of these tasks. As Satterfield, Satterfield, and Cantwell (1981) noted, and more recently Foy and Earls (2005), the classroom teacher is a major determining factor in whether a student is correctly diagnosed with ADHD and whether they succeed or fail in the classroom.

Background Information

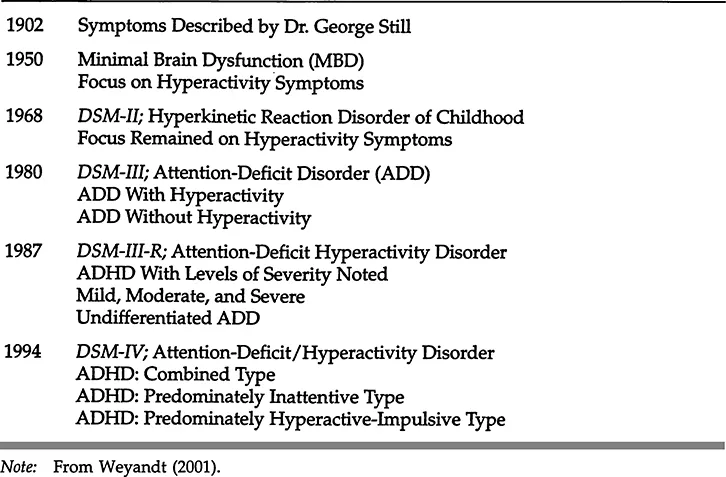

According to Dr. Roscoe Dykman (2005) the symptoms now associated with ADHD have been recognized in children since the 1800s and, in fact, appeared in a nursery rhyme written by Heinrich Hoffman in 1863. George Still (1902), a physician who presented a series of papers to the Royal College of Physicians, is typically credited for formally identifying ADHD symptoms in children, although others have also been recognized as pioneers in the field (see Dykman, 2005, for a review of the historical information). Following Still’s work, clinicians and researchers asserted that these symptoms were likely due to brain damage, and, despite lack of physiological evidence for this claim, the term minimal brain dysfunction (MBU) emerged during the late 1940s and the 1950s (e.g., Brown et al, 1962; Clements & Peters, 1962; Strauss & Lehtinen, 1947). During the 1960s, the research focus shifted to the overt, hyperactivity symptoms. In 1968, the second edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-II) was published (American Psychiatric Association, 1968) and for the first time included the diagnostic category hyperkinetic reaction disorder of childhood. According to the DSM-II, the central hallmarks of the disorder were hyperactivity, distractibility, and attention problems. It was believed at this time that children would outgrow the disorder by adolescence.

Table 1.1 Historical Information

During the 1970s, the research emphasis shifted from hyperactivity to attention problems. This focus was reflected in the new diagnostic label, attention deficit disorder (ADD), published in the third edition of the DSM (American Psychiatric Association, 1980). According to DSM-III, two subtypes of ADD existed— ADD with or without hyperactivity. In 1987, the DSM-III was revised (DSM-III-R), and, although the label remained the same (i.e., ADD), the emphasis was now on the presence and pervasiveness of three core symptoms—inattention, im-pulsivity, and hyperactivity (American Psychiatric Association, 1987). ADD without hyperactivity was no longer recognized as a specific subtype of ADD and was instead categorized as undifferentiated ADD. In 1994, the fourth edition of the DSM was released, and the diagnostic category ADD was changed to ADHD (attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder). Three new subtypes were delineated—ADHD, predominately inattentive type-, ADHD, predominately hyperactive-impulsive type; and ADHD, combined type (see Table 1.1 for a summary of this information).

Differences in Subtypes

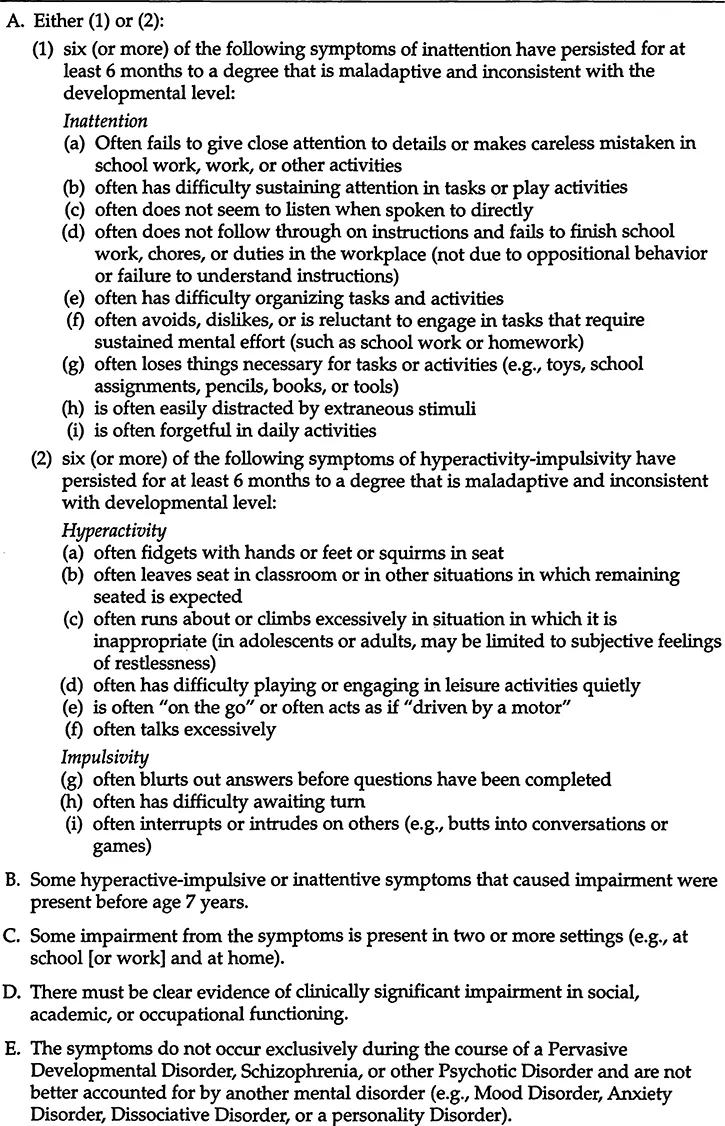

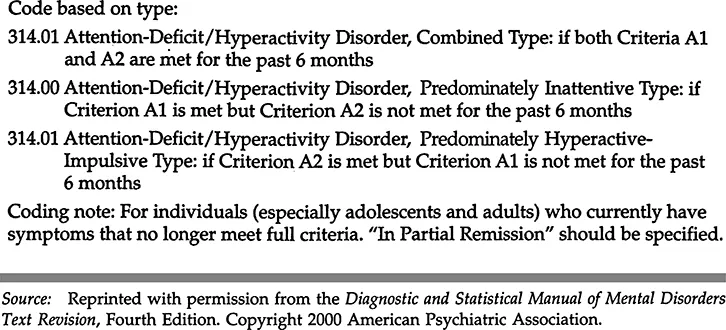

Research indicates that the three ADHD subtypes can be reliably diagnosed (see Table 1.2) and may have clinically meaningful differences. For example, a study by Morgan, Hynd, Riccio, and Hall (1996) found that children with ADHD, combined type, have more behavioral and acting out problems, while children with ADHD, predominately inattentive type, have fewer behavioral but more learning problems. More recently, Carlson and Mann (2002) reported that children with ADHD inattentive subtype were rated by teachers as having fewer behavioral problems but higher levels of anxiety, depression, unhappi-ness, and withdrawn behavior. Bauermeister, Matos, and Reina (1999) found the family is impacted differently depending on the ADHD subtype a child or adolescent might have. Specifically, Bauermeister and colleagues found that mothers of children with ADHD, combined type, reported (a) more negative feelings such as frustration, and less positive feelings toward their children; and (b) a greater negative impact on family social life and relationship with teachers, compared to mothers of children with ADHD, predominately inattentive type. With regard to age and subtype, studies suggest that the predominately hyperactive-impulsive subtype is most often associated with younger children and the predominately inattentive type is associated with older children in the United States as well as in other countries (McBurnett et al., 1999; Nolan, Gadow, & Sprafkin, 2001; Pineda et al., 1999). On behavioral tasks, several studies have found performance differences among children with different subtypes of ADHD. For example, Collings (2003) reported that children with ADHD combined type committed a greater percentage of omission errors on a continuous performance task, and their performance deteriorated more quickly, relative to children with ADHD inattentive type (and children without ADHD). Todd et al. (2002) studied achievement and cognitive performance of a sample of child and adolescent twins with ADHD and found that those with the combined subtype and inattentive subtype made significantly worse grades and achievement testing scores, and had an increased use of special education services compared to those twins with hyperactive/impulsive subtype of ADHD. Clark and colleagues (Clark, Barry, McCarthy, & Selikowitz, 2001) compared EEG recordings of children with ADHD combined type versus inattentive type and reported that those with combined type had an increase in fast-wave activity in the frontal regions of the brain. Although these findings are inconclusive, they do suggest that distinct physiological differences may exist between different subtypes of ADHD. Murphy, Barkley, and Bush (2002) conducted one of the few studies to compare subtype differences among young adults with ADHD (ages 17-27) and found that those with ADHD combined type were more likely than those with inattentive subtype to have been arrested, attempted suicide, to have oppositional defiant disorder, and hostility problems. These authors as well as others have suggested that the greater impulsivity associated with the combined subtype may increase the likelihood that young adults with ADHD will engage in antisocial behavior. It is important to note, however, that Murphy, Barkley, and Bush found that young adults with ADHD combined and inattentive subtypes did not differ on a number of dimensions such as co-existing psychiatric conditions, psychological distress, use of mental health services, and use of illegal drugs. In addition, a number of studies have failed to find cognitive or behavioral differences between individuals with subtypes of ADHD (e.g., Corkum & Siegel, 1993; Milich, Balentine, & Lynam, 2002) and the majority of studies have been conducted with children. Furthermore, some studies have reported subtype differences on a few but not all neuropsychological tasks (Schmitz et al., 2002). Additional research is needed to determine whether distinct behavioral, cognitive, academic, and neurophysiological differences exist among children, adolescents, and adults with different subtypes of ADHD.

Table 1.2 Diagnostic Criteria for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

Current Criteria

The DSM-IV was published in 1994 and the DSM-IV Text Revision was released in 2000. The diagnostic criteria for ADHD did not change from the fourth edition to the Text Revision of the DSM and the current diagnostic criteria appear in Table 1.2. The diagnostic criteria for ADHD require that an individual display significant and developmental^ inappropriate levels of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity. These symptoms must be present early in life; exist in two or more settings; and cause social, educational, or occupational impairment. It is important to recognize that nearly everyone is inattentive, hyperactive, or impulsive in some situations and that the mere presence of ADHD symptoms does not equal a “disorder.” Furthermore, symptoms associated with ADHD, particularly inattention, can also be characteristic of many other disorders such as learning disabilities, sleep disorders, substance use, and emotional problems, to name a few. As Gordon and Barkley (1999) aptly stated, “inattention as a symptom resembles fever or chest pains in that its presence alone does little to narrow the field of diagnostic possibilities” (p. 2). To arrive at a valid ADHD diagnosis, a thorough evaluation is required.

DSM-IV Limitations

The current diagnostic criteria are an improvement over DSM-HI-R (1987) criteria as they are based on research studies and they include a requirement of impairment in social, academic, or occupational functioning. Problems remain, however, as some experts in the field argue that ADHD, predominately inattentive type should be a separate, distinct, and independent disorder from ADHD (Barkley, 1998, p. 65). Indeed, results from several studies suggest that, statistically, DSM criteria tend to fall into two, rather than three, categories. For example, Beiser, Dion, and Gotowiec (2000) examined parent and teacher ratings of 1,555 Native and 489 non-Native children from the United States and Canada and found a two-factor solution; attention versus hyperactive-impulsive symptoms. Similar findings have been reported with Icelandic children (Magnusson, Smari, Gretarsdottir, & Prandardottir, 1999), Brazilian children (Rohde et al., 2001), and others (e.g., DuPaul, McGoey, Eckert, & Van Brackle, 2001; Wolraich, Lambert, Baumgaertel, et al., 2003). The usefulness and stability of the ADHD, predominately hyperactive-impulsive, subtype has also been questioned. For example, Lahey, Pelham, Loney, Lee, and Willcutt (2005) conducted an 8-year longitudinal study of 4- to 6-year olds who met DSM-IV criteria for ADHD and found that most children, over time, continued to meet diagnostic criteria for the disorder. Of the three subtypes, however, children with the hyperactive-impulsive subtype rarely met the criteria for this subtype over time. An additional problem with the current diagnostic criteria concerns the questionable developmental appropriateness of the items for children, adolescents, and adults. For example, earlier research by Hart, Lahey, Loeber, Applegate, and Frick (1995) indicated that the symptoms of ADHD changed during childhood and adolescence and specifically that problems with attention remain relatively persistent while hyperactivity and impulsivity symptoms appear to decline with age. More recently, Biederman, Mick, and Faraone (2000) followed 128 boys with ADHD for a period of 4 years and also found that ADHD symptoms tended to decline with age, and the most significant decline in symptoms was with hyperactive, impulsive symptoms. Similar age-related changes have been reported by others (e.g., Drechsler, Brandeis, Foldenyi, Imhof, & Steinhausen, 2005; Kato, Nichols, Kerivan, & Huffman, 2001). These findings, however, are likely due in part to the diagnostic criteria which are not age-referenced and are limited in number with regard to hyperactivity and impulsivity relative to inattention (i.e., nine for inattention, six for hyperactivity, and three for impulsivity). Indeed, Spencer, Biederman, Wilens, and Faraone (2002) suggested that the current criteria for ADHD may minimize, or underestimate, the actual rate of persistence of ADHD into adulthood. Given the concerns expressed in the literature and the ongoing research in this area, it is likely that the diagnostic criteria for ADHD will be revised in future editions of the DSM and reflect more age-appropriate items. It is also likely that the subtypes will be revised and may reflect statistical studies that support two primary dimensions (attention, impulsivity/hyperactivity) rather than three.