![]()

Methodological Issues

Travis Hirschi

John H. Laub

![]()

1

Principles of Causal Analysis

Travis Hirschi

Hanan C. Selvin

From many sources, the principles of association, causal order, and nonspuriousness discussed in this selection are now part of the common sense of informed discourse. (Discourse that remains hard to find in current discussions of the so-called causes of delinquency.) They are especially significant in evaluating Hirschi's work because they impressed him early in his training, because they are independent of substantive theory, and because he relies so frequently on them in subsequent work. Paul Lazarsfeld and his colleagues honored this chapter from Hirschi and Selvin's Delinquency Research: An Appraisal of Analytic Methods by reprinting it in their Continuities in the Language of Social Research (Free Press, 1972). When asked to recall how the chapter came about, Hirschi focused on Table 2. “Table 2 is in some ways the heart of the entire book. I saw it my first semester in graduate school (1960) as a teaching assistant to William Nicholls, who did a great job with it in statistics lectures. It came to him from an article by Sheldon and Eleanor Glueck by way of an article by Eleanor Maccoby, who had repercentaged it to good effect. Seven years(!) later, Selvin and I could be found using it to illustrate a variety of analytic principles. All of which shows how much interest there was at the time in clean and clear illustrations from real data of Lazarsfeld's elaboration model, and how hard they are to find.”—JHL/TH

We begin by accepting the idea that it is possible and meaningful to discuss such propositions as, Inadequate supervision is a cause of delinquency, and, Assigning street workers to gangs causes a reduction in the rate of serious delinquency. Both of these propositions are of the form A causes B; we shall speak of A as the independent variable and B as the dependent variable. The typical question that the empirical investigator faces is how to test such propositions, i.e., how to collect and treat empirical data so as to make reasonable statements about causal hypotheses.

In the empirical social sciences there is general agreement on the criteria for evaluating such statements. Our central task, then, is to apply these criteria to the analysis of empirical data. We shall have very little to say about the sources of hypotheses, the nature of abstract theory, and such broad philosophical problems as inductive inference.

Criteria of Causality

In Hyman's account (1955: chaps. 4-7) there are three principal requirements that an empirical investigator must meet in order to be able to say that A causes B:

A and B are statistically associated.

A is causally prior to B.

The association between A and B does not disappear when the effects of other variables causally prior to both of the original variables are removed.

We shall consider A a cause of B if all three of these criteria are satisfied; it follows that demonstrating any one of the three to be false is enough to show that A is not a cause of B. For simplicity we shall refer to these three criteria as association, causal order, and lack of spuriousness.

Hyman also advocates another criterion: that one or more intervening variables link the independent and dependent variables. This criterion is psychologically, substantively, and even aesthetically desirable; knowing the process through which A affects B is more rewarding to the investigator than the bare statement that A causes B. Nevertheless, this criterion is not part of the minimum requirements for demonstrating causality. Holding a match to a pile of leaves is a cause of their bursting into flame, even if one cannot describe the intervening chemical reactions.

Experimentation and Observation

Consider the two propositions: Inadequate supervision is a cause of delinquency, and, Assigning street workers to gangs causes a reduction in the rate of serious delinquency. Although these two propositions are formally similar in having an independent and a dependent variable, they differ fundamentally in the kinds of studies that may be used to test them. The investigator of inadequate supervision must take children as he finds them; he cannot decide that this child's mother shall adequately supervise him and that that child's mother shall not. In other words, he cannot manipulate the values of his independent variable. The investigator of juvenile gangs can, however, decide which gangs will receive street workers and which will not. It is this ability to manipulate the values of the independent variable that makes experiments possible.

One additional ingredient is necessary for a genuine experiment (Fisher 1953). The investigator must use some chance mechanism to determine which gangs get a street worker and which do not. For example, he might toss a coin for each gang, assigning a street worker if the coin falls heads. This randomization allows the experimenter to deal with unwanted or extraneous causal variables and thus to satisfy our third requirement for making a causal inference: that the association between the independent and dependent variables does not result from their having a common cause.

To see why this is so, consider two procedures that the investigator might use instead of randomization in assigning street workers to gangs: (1) allow the gangs to decide for themselves whether or not they will get a worker; or (2) make the decision himself on any basis that he chooses. The objection to the first procedure is clear. If he lets the gangs decide for themselves, the more law-abiding gangs may choose to have workers; any subsequent difference in the rates of serious delinquency may be the result of such differences in the gangs themselves rather than the effects of the street workers. The objection to the second procedure is less obvious but equally cogent. Even with the best of intentions the investigator may unknowingly assign street workers to groups that are less predisposed to serious delinquency. No matter what basis of choice is used, any purposive assignment is open to a similar objection.

Randomization, however, meets this objection. If the decision to assign a street worker is made at random, the presence of street workers cannot be associated with any other characteristic of the gangs, such as their predisposition to violence. At least this is what will happen on the average: The number of gangs predisposed to violence among those getting a street worker will be approximately equal to the number predisposed to violence among those not getting a street worker, so that there will usually be a small or zero association between a gang's predisposition to violence and the presence of a street worker.

It is always possible, however, that the process of randomization does not completely remove the association between the extraneous variable and the independent variable. Just as one may get ten heads in ten tosses of an unbiased coin, so randomization may occasionally give more street workers to docile gangs than to violent gangs. With the techniques of statistical inference, it is possible to calculate the probability of such an occurrence. That is, in advance of gathering the data, an experimenter can decide how strong the results must be in order to be reasonably confident that they are not simply the accidental outcomes of randomization.

Although randomization is necessary for a good experiment, it is not sufficient. The field known as the statistical design of experiments is largely devoted to ways of making randomized experiments more powerful and more precise. Here, however, we need pursue this line of thought no further, for there are few areas of research on the causes of delinquency in which one can legitimately experiment. As our proposition about street workers illustrates, experimental research usually deals with the treatment of delinquency rather than its causes. In the far larger number of studies represented by our proposition about supervision the investigator must look to other ways of ensuring that extraneous variables have not produced the observed association between his independent and dependent variables.

Suppose that an investigator has found a relation between inadequate supervision and delinquency. He might then reason:

Inadequately supervised children are likely to come from broken homes, and broken homes are known to be associated with delinquency. Since broken homes are causally prior to both variables of the original relation, could the apparent meaning of the original relation be spurious, i.e., could it have come about through the associations of broken homes with both of the original variables rather than through the effect of inadequate supervision on delinquency?

Unlike the experimenter, the nonexperimental investigator cannot use randomization to remove the association between his extraneous variable and the independent variable. Instead of controlling extraneous variables in the design of the study, he relies on statistical manipulation of the data after they have been gathered.

This statistical analysis can take many forms, including partial correlation, standardization, analysis of variance, and the construction of multivariate tables (cross-classification or cross-tabulation). Although there are reasons to believe that more powerful statistical methods will eventually replace cross-classification as a tool of investigation, most empirical studies of delinquency have relied on tabular analysis. Moreover, tables remain the clearest and simplest way to present the conclusions of an analysis. For these reasons both our examples and our methodological analyses will rely on tables.

Statistical Configurations in Analysis

Consider once again the proposition: “Inadequate supervision is a cause of delinquency.” The first task of the analyst who wants to test this proposition is to see whether the two variables, supervision and delinquency, are associated—that is, whether there is a difference in the proportion of delinquents between adequately supervised boys and inadequately supervised boys.

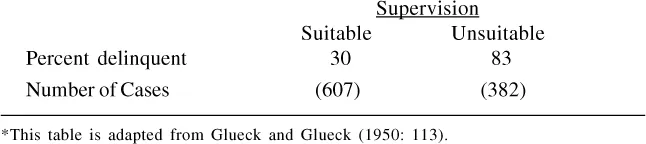

In Table 1.1, the proportion delinquent among the suitably supervised boys is 30 percent, while the proportion delinquent among the unsuitably supervised boys is 83 percent, a difference of 53 percentage points.

We are using percentage comparisons to describe the association between two variables; we might have used one or another summary measure of association, such as a correlation coefficient, Yule's Q, Cramer's T, or the more modern measures developed by Goodman and Kruskal (1954). The numerical estimates of the association would differ depending on the coefficient used, but all would lead to the conclusion that there is a moderate association between supervision and delinquency.

Table 1.1 Delinquency by Suitability of Supervision*

After measuring the association, the analyst must demonstrate that his independent variable, supervision in our example, is causally prior to his dependent variable, delinquency. There are serious problems in this demonstration, as we shall show; however, these problems are not tabular or even statistical in the usual sense of that term.

In demonstrating lack of spuriousness, the third criterion of causality, the analyst goes beyond the two-variable table to examine three-variable relations, or even more complicated configurations. It will suffice here to consider only the simplest form, the three-variable table.

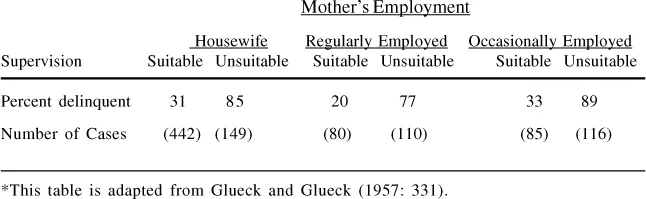

Table 1.2 permits reexamination of the relation between the suitability of supervision and delinquency, with mother's employment held constant.1 In this case, the proposed antecedent variable, mother's employment, does not affect the relation between suitability of supervision and delinquency: The relation is as strong within categories of mother's employment as it is when mother's employment is left free to vary (see Table 1.1). The analyst can thus conclude that the observed relation is not spurious, at least with respect to mother's employment. (Following Lazarsfeld, we shall refer to the disappearance of a relation as explanation when the third variable is causally prior to the independent variable and as interpretation when the third variable intervenes between the independent and dependent variables.)

This, then, is the basic procedure for demonstrating causality: Starting with an association between a causally prior independent variable and a dependent variable, the analyst considers possible antecedent variables that might account for the observed relation. If he finds such a variable, he declares that the apparent causal relation is spurious, and he moves on to a different independent variable. If he fails to find the original relation spurious, he tentatively concludes that his independent variable is a cause of his dependent variable.

Table 1.2 Delinquency and Suitability of Supervision by Mother's Employment*

This conclusion must be tentative, for it is always possible that another a...