![]()

Part I

The noble art of counting beans

![]()

Chapter 1

Stewardship reporting: the physical dimension

Record Keeping

To some extent accounting is a prisoner of its historical development. It probably developed from the need, even in the Ancient world, for records (a) of asset holdings and (b) of relations with other parties. It was not until the growth of commerce in the Middle Ages, however, that the system of double-entry bookkeeping evolved. (Pacioli’s famous treatise on the system employed in Venice was published in 1494.) Both objectives were realized simultaneously by the ‘dual classification’ of resources, (a) according to the nature of the resources, and (b) according to the ‘equity’ in those resources.

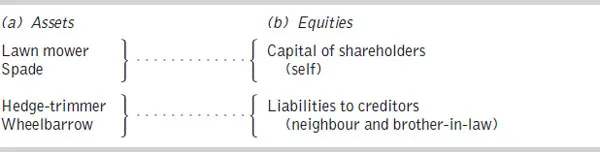

Table 1.1 illustrates the application of the double-entry principle to the contents of a garden shed. The left-hand side satisfies the first requirement by classifying the contents of the garden shed ‘according to the nature of the resources’. The right-hand side satisfies the second requirement by classifying the contents of the garden shed ‘according to the equity in those resources’. This dual classification of resources gives a ‘true and fair’ view: it shows clearly (a) what is in the shed, and (b) to whom it belongs.

Table 1.1 List of items in the garden shed at 31 March

(a) Nature of item | (b) Owner of item |

Lawn mower | Self |

Hedge-trimmer | Next-door neighbour |

Spade | Self |

Wheelbarrow | Brother-in-law |

Although it is a comprehensive list of the contents of the garden shed, it is no more than that. This type of record keeping is sometimes dismissed as mere ‘bean counting’. It provides no information whatever on the physical condition of the items; nor does it give any indication of their economic value. Nevertheless, it is essential in the operation of most businesses.

It is rather like the cataloguing system used in a library, where books are normally classified (a) by subject and (b) by borrower. Without a catalogue, it would be impossible to ‘keep track of the stock’. In order to run a business, it is also necessary to ‘keep track of the stock’. The cataloguing system is the ‘double-entry’ method used for the items in the garden shed. If the Garden Shed is a limited company, the list is same, but some of the labels are different.

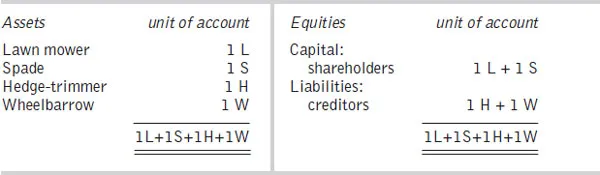

The items ‘in the business’ are called ‘assets’ (from which future benefits are expected). The ‘equities’ (or claims on the assets) are subdivided into two main categories: equities belonging to the company’s owners (the shareholders) are called ‘capital’; and equities belonging to outsiders (the creditors) are called ‘liabilities’. These categories are shown in Table 1.2.

Table 1.2 List of items in the Garden Shed Company Ltd at 31 March

To convert the list into a balance sheet, all the assets and all the equities need to be stated in terms of some ‘unit of account’. Accounting in terms of physical units (Goldberg, 1965: 42) achieves perfect accuracy in Table 1.3.

Table 1.3 (‘Physical’) balance sheet of the Garden Shed Company Ltd at 31 March

Where there are numerous assets of many different types, however, complex physical expressions are not very practical for published accounts. A common denominator is required; and the universal choice for the role of unit of account is money.

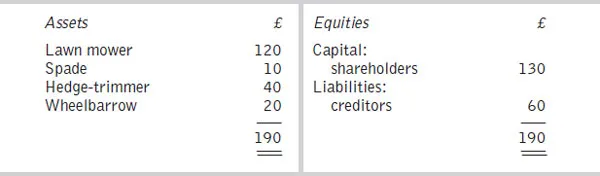

This raises what is perhaps the oldest and most difficult accounting problem of all. How are the physical units to be converted into money? The most convenient method is to use the objectively verifiable evidence of an actual transaction. The original (’historical’) cost, for which there is usually the documentary evidence of a purchase invoice, is the traditional choice.

Suppose that the original purchase cost of each of the items is known: £120 for the lawn mower, £10 for the spade, £40 for the hedge-trimmer, and £20 for the wheel-barrow. The use of money as the unit of account is illustrated in Table 1.4.

Table 1.4 (‘Monetary’) balance sheet of the Garden Shed Company Ltd at 31 March

Compared with the ‘physical’ balance sheet, the ‘monetary’ balance sheet shows a clear gain in mathematical elegance; and it does so without any loss of information. It still gives a complete picture of the items in the shed and to whom they belong. It indicates that, in the Garden Shed (Company), there are garden tools (assets) with a total cost of £190. Of that total, tools costing £130 belong to the owner, and tools costing £60 belong to other parties (the next-door neighbour and the brother-in-law). No information appears to have been lost, but some has been gained: the balance sheet now includes details of cost.

A double-entry system based on historical cost is ideal for the purpose of ‘keeping track of a firm’s assets’ – for ‘counting the beans’. It is therefore ideal for the purpose of ‘stewardship reporting’ in the narrow sense to be discussed in the next few paragraphs.

The Distinction between ‘Stewardship’ and ‘Performance’

In its Statement of Principles for Financial Reporting, the UK Accounting Standards Board makes clear that it ‘regards stewardship as being not merely about the safekeeping and proper use of an entity’s resources but also about their efficient and profitable use’ (2005: 89). This echoes the view of the US Financial Accounting Standards Board on the ‘stewardship responsibility [of management] for the use of enterprise resources entrusted to it’.

Management of an enterprise is periodically accountable to the owners not only for the custody and safekeeping of enterprise resources but also for their efficient and profitable use… . Management, owners, and others emphasize enterprise performance or profitability in describing how management has discharged its stewardship accountability.

(1978: 25)

In this book, by contrast, the opposite line is taken. ‘Stewardship reporting’ on ‘the custody and safekeeping of enterprise resources’ is clearly distinguished from ‘performance reporting’ on ‘their efficient and profitable use’.

On the meaning of ‘performance’, however, this book takes the same view as the standard-setting bodies. ‘The financial performance of an entity comprises the return it obtains on the resources it controls, the components of that return and the characteristics of those components’ (ASB, 2005: 27; cf. FASB, 1978: 19).

It is difficult to compare the performance of firms of different sizes with each other or with alternative forms of investment in any other way. This supports the view that ‘the rate of return’ is ‘the most important matter that the accountant has to deal with in a year’s reports’ (Canning, 1929: 259).

Throughout this book, therefore, a clear distinction is maintained between stewardship reporting on the ‘safekeeping’ of resources and performance reporting on their ‘efficient use’. The argument developed in Parts I to IV is that information designed for one purpose is frequently inappropriate for the other. The result is a ‘hybrid’ system of accounting in which records of fact are mixed up with estimates of value. The solution proposed in Part V is a ‘segregated’ system of accounting in which ‘stewardship reporting’ is kept strictly separate from ‘performance reporting’.

‘Stewardship Reporting’ on the ‘Safekeeping’ of Resources

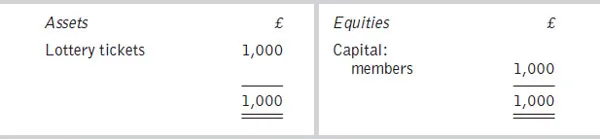

Suppose that a syndicate is formed for the purpose of buying £1 lottery tickets. Managers are appointed to collect the money, to buy the tickets, and to choose the numbers. There are 100 members in the syndicate, and each one contributes £10. The syndicate managers are therefore in charge of £1,000 of other people’s money.

How can members of the syndicate be sure that (1) the whole of the £1,000 is actually spent on lottery tickets, and (2) the whole of any prize money is paid in to the syndicate? One answer is the installation of a system of ‘internal control’ for the detection of fraud or error together with the appointment of an independent auditor to report on the system. An effective system normally requires division of responsibility – with a clear separation between those who handle the assets and those who keep the records.

No audit procedure can prevent mistakes or misappropriation, but, by making it as difficult as possible to escape detection, it can operate as a powerful deterrent.

Without any audit procedures, there is no way of telling whether syndicate managers are (1) using all the contributions to buy tickets and (2) paying in the whole of any prize money. An effective system of ‘internal control’ would probably include procedures to be carried out by people who are independent of the managers:

- compilation of a record (before the draw) of the 1,000 sets of numbers;

- inspection without notice to verify the holding of cash or tickets totalling £1,000;

- calculation (after the draw) of prize money (by checking the record of numbers against a published list of winning numbers).

It is normal practice for the auditor to test the system and to verify the accounts. The balance sheet, on the day before the draw, is shown in Table 1.5.

Table 1.5 Balance sheet of the syndicate on the day before the draw

If the auditors are satisfied with the operation of the system of internal control, they are entitled to report that the balance sheet fulfils...