Chapter 1

- Overview

- Introduction

- What is attention?

- Selective attention

- Divided attention

- Control of attention

- Vigilance

- Summary

Everyone knows what attention is. It is the taking possession of the mind, in clear and vivid form, of one out of what seemed several simultaneously possible objects or trains of thought. Focalization, concentration, of consciousness are of its essence.

—William James (1890)

Overview

THIS CHAPTER COMMENCES with a brief introduction to the topic of attention. It then goes on to introduce the relevant cognitive theories to the reader (or revise the concepts for those who have previously studied the subject). These theories will recur as subsequent chapters describe how they have guided research with various types of patients. Clearly, then, a good grasp of the material in this chapter will be essential to fully appreciating that presented in later chapters. Readers who are familiar with the various theories may choose to skip this chapter or concentrate on those sections that deal with unfamiliar material.

Introduction

Our ability as human beings to selectively focus our attention on specific features of our environment is undoubtedly of fundamental importance in allowing us to adapt to an ever more complex and richer world. Take a common experience, such as standing on the concourse of a major railway station or airport, and imagine all the sights and sounds bombarding your senses and demanding recognition. Were you not able to screen out some of this abundance of stimuli, then such an experience would be daunting indeed. The study of these key mental processes has become the concern of a major strand of modern psychology, the study of cognition. This area of psychology has been a major part of the discipline for over 40 years and, from the outset, the study of attention has been an important element, for example with the publication of a highly influential work by Broadbent in 1958. Since that time, psychologists have sought to take real-world problems, such as how we deal with several sounds simultaneously, and study them in the laboratory under carefully controlled conditions.

Over the last few decades many hundreds if not thousands of such studies have focused upon the topic of attention, looking at the phenomenon from many different angles. The observations and data gathered have led to a number of theories explaining how humans attend to their environment. More recently, clinical psychologists have come to realize that these cognitive theories can provide a very useful framework for understanding the problems of their patients. At the same time, cognitive psychologists have come to see that observing the difficulties experienced by patients with certain conditions can be a useful source of additional data. This evidence can serve to confirm or discredit those theories, often provoking revision and reconsideration. This synergy between basic laboratory-based research and clinical work with patients has in recent times led to additional interest in the area of cognitive science. The joint efforts of neuroscientists and cognitive psychologists are now seen as indispensable to a fuller understanding of the human brain. The aim of this book is to illustrate for the reader how this process has enhanced our understanding of attention and its disorders. Twenty years ago a book on cognitive neuropsychology (the application of cognitive theories to neurological disorders) would have been difficult to write, since the approach was in its infancy. Ten years ago, such a book focusing on attention would have been just as difficult to conceive, since the early neuropsychological research tended to focus on memory and language. It is interesting to note, for example, that an important text on the neuropsychology of dementia, published just over a decade ago (Hart & Semple, 1990), contained only a very modest section on attention. In the last 10 years this situation has changed dramatically. Many neuropsychologists realized that the lack of research on attention represented a major omission from the knowledge base. Further, many suspected that attentional processes were really at the core of difficulties experienced by many patients, which were being described as memory or other deficits. For example, we now know that patients with Alzheimer’s disease often exhibit severe attentional difficulties in the early stages of the disorder, often before symptoms have manifested themselves in other areas (e.g. Parasuraman & Haxby, 1993).

As a result of this increased interest in the topic, it is now possible to consider the neuropsychology of attention as an area in its own right, and this book sets out to introduce readers to this domain. Given its youth, there is no doubt that this area of work will experience considerable progress in the years ahead. Should any of the readers of this book come to be involved in that endeavour, having been inspired by these pages, then it will have admirably served its purpose. It is also the author’s hope that this introduction to the neuropsychology of attention will prove useful to clinicians working with the various types of patient who suffer from the disorders that will be considered.

What is attention?

Cognitive theories of attention can seem very complex and abstract. In reality, these theories are trying to describe quite simple aspects of behaviour that we can all understand. To help the reader, therefore, each of the following sections briefly considers everyday examples of behaviour, which are thought to involve the aspects of attention being described. Subsequently, the theoretical accounts psychologists have given for those behaviours will be reviewed. The various theories of attention can be covered under the headings of selection, dividing attention, control, and vigilance.

Selective attention

The quote given at the start of this chapter seems to have become de rigueur as a way of opening discussions such as this on the nature of attention. James’ view is that the term “attention” refers to the process by which we are able to focus on a particular aspect of our environment. Thus that aspect becomes the only thing we are aware of at that particular moment in time. Probably one of the best examples of this in the modern world is the experience of watching television. When we are engrossed in a favourite television programme we may be unaware of other things happening in the room around us. We may not hear someone in the room asking us a question, or may be unaware of events taking place outside. However, at any given time we can change the focus of our attention. As James pointed out, our own trains of thought may distract us, causing us to shift our focus, perhaps gazing out of a window to see if it has started to rain, or listening intently to hear if the washing machine has stopped. In a modern home there are many such distractions, leading us to take precautions when we are especially keen to concentrate on something, e.g. by unplugging the phone. The cinema is the classic example of distraction management, leading many of us to emerge blinking after 2 hours of total immersion from a world of undistracted movie fantasy. This may be the reason why cinemas remain popular in this era of unlimited home entertainment.

The modern phenomena of television is an example of a multi-sensory stimulus capable of holding our attention for considerable periods of time, but we could cite simpler examples of focused attention that use a single sense. For example, a street map is a simple device that allows any of us to pinpoint an unfamiliar location in unknown territory. To use it, we have to look up in the index a grid reference for the street we want to find and then scan that grid of the map for our location. In this example, the focus of our attention is visual. A similar experience is scanning a telephone directory for a particular name. In both examples we are focusing our vision on a particular location, and trying to select a particular stimulus from a range of items. Imagine if the telephone directory was particularly large, or the street map especially dense. What would determine how successful we were in our task, i.e. how quickly we could find the desired name or street? Clearly we would need to stay very focused on the directory or map, not allowing ourselves to be distracted. Imagine carrying out such a task in a quiet room at home compared to a busy shopping centre or on a busy main road. Also, we would need to concentrate on finding the particular name or street, not being distracted by other items on the map or names in the directory. It also helps that modern maps tend to use a variety of very different symbols to represent different types of land-based features.

Moving to an auditory example, we often find ourselves in a noisy environment, having to focus upon a particular stimuli while trying to ignore a multitude of competing sounds. Imagine, for example, trying to have a conversation in a busy café with many competing sounds going on around. Many of us will know how difficult it is to make phone calls from such difficult environments as railway station concourses. In such situations we have to concentrate on one particular conversation, while trying to ignore the sound of other voices competing for our attention. Many of us will also have had the experience of having a conversation with someone in which we have only a partial interest, and finding it very difficult to ignore a conversation going on nearby in which we have a much greater interest. Imagine, for example, that you are at a party and find yourself talking to someone about last weekend’s football results, when you would be much more interested in talking about office politics and in fact someone nearby is discussing the latest list of office promotions and appointments. Under such circumstances many of us would find ourselves distracted by the conversation going on nearby, and perhaps even be embarrassed at the frequency with which we might find ourselves having to ask our footballing acquaintance to repeat crucial facts.

All of the above examples show how, in the real world, we often choose to focus on a particular stimuli, either auditory or visual. In fact if we reflect a little more, it is not that we choose to select, but rather that we are forced to, as we are not able to attend to everything at once; we can only focus on one conversation at a time. Even if we install two televisions in our lounge so as to be able to watch more of our favourite programmes, we will struggle to follow what is happening on them simultaneously. Provided we focus our attention on a single source of information, i.e. one television or one conversation, we are able to perform the task with relative ease, but at the expense of becoming less aware of other things going on around us.

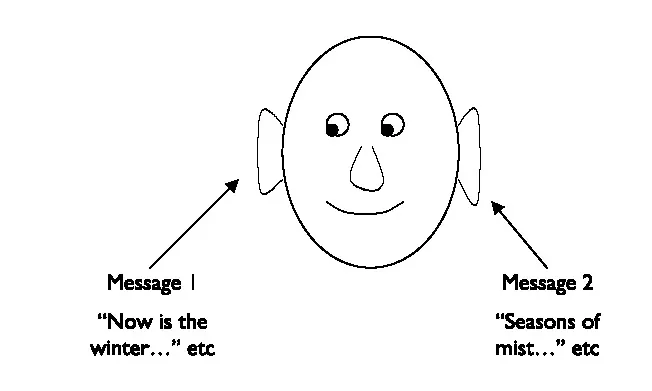

These kinds of common-sense reflections are found in the earliest theories of attention. For example, Cherry (1953) studied the “cocktail party” phenomenon. This relates to the situation in which we are able to follow a single conversation even when there are many other conversations going on around us, the kind of situation we encounter at parties. To control this situation in the laboratory, Cherry devised the Dichotic Listening Test (Figure 1.1). This involves the independent playing of two messages through headphones, one to either ear. To ensure that participants attend fully to the voice in one ear, they are typically asked to shadow that message, i.e. to repeat it out loud. Sometimes the messages presented are text passages, sometimes they may be letter or number strings. So a participant may hear “now is the winter of our discontent . . .” Played to the right ear and “Remember thy creator in the time of thy youth . . .” played to the left. If they were asked to shadow the right then they would say out loud “now . . . is . . . the . . . winter . . .” and so on in synchrony with the recording. This is a very effective technique for ensuring that participants listen only to the message to be attended. The question then is, what if anything do they notice about the unattended message? The answer according to Cherry was remarkably little, other than the gross physical characteristics, e.g. the pitch and timbre of the voice. Participants could not recall anything of what was actually said, and frequently even failed to notice if the unattended message were being presented in a foreign language!

Figure 1.1 The dichotic listening task

Two messages are played to the participant simultaneously, one to each ear. The participant then has to repeat out loud one of the messages (shadow), so he or she would say “now is the winter . . .” etc if asked to follow the right ear.

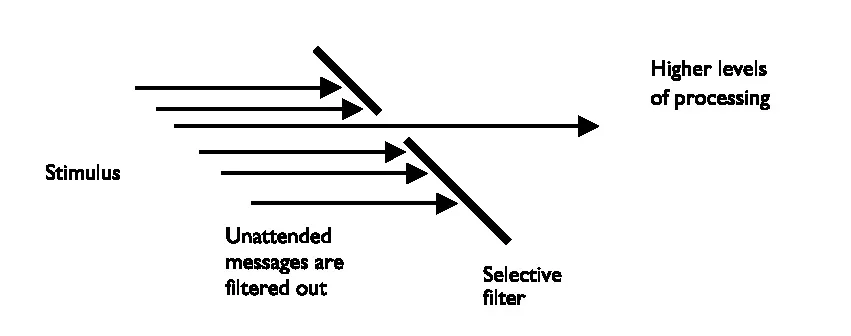

In his influential 1958 book, Broadbent theorized about the nature of these observations. He proposed that the human attentional system must have a limited capacity, since there is a very finite limit on how much information we can attend to at once. Further, since this capacity can be applied to a wide variety of tasks and situations, e.g. reading a book, looking at a map, or holding a conversation, it must be general purpose. To protect this limited capacity, Broadbent proposed that our attentional system was set up to process one information source at a time, what he termed a “single channel”. All other unattended channels would be filtered out, and this filtering was done based on gross physical characteristics (Figure 1.2). Thus the only thing that participants would be aware of in the unattended channel during the dichotic listening task would be the gross physical features. The theory could account for all the data collected at the time, and seemed a plausible account.

Within a few years, however, other workers were raising difficulties for Broadbent’s account. One of Broadbent’s former PhD students pointed out that sometimes information could intrude from the unattended channel (Treisman, 1960, 1964). For example, if participants were asked to tap each time they heard the word “tap” in the attended channel, then occasionally they would tap in response to the word being presented on the unattended channel. According to Broadbent’s account this should not happen (although the possibility that participants might actively be shifting their attention during the task does not seem to have been adequately considered—see later). In another elegant experiment, Corteen and Dunn (1971) conditioned words to produce a galvanic skin response (GSR) response (a stress reaction based on increased perspiration) by being paired with a mild electric shock. They found that such words continued to elicit a GSR even when presented in the unattended channel during a shadowing task. Treisman’s solution to this difficulty was to propose a modification of Broadbent’s theory, such that unattended information was not completely filtered out by the attentional system, instead it was “attenuated”. Thus information from the unattended channel is not lost to higher processes, but it is not as readily available, in a sense it is “turned down” (Figure 1.3). An alternative and quite different view was put forward by Deutsch and Deutsch (1963), who suggested that no filtering or attenuation takes place, instead all inputs are fully processed and available. However, since unattended inputs are not selected for any further processing, they are very quickly lost. In this account information to be attended to is determined partly by “pertinence”, i.e. its relevance to the current context and task demands (Figure 1.4). This can explain why a participant’s name is frequently able to draw his or her attention when presented in the unattended channel. Such highly relevant and personal information as one’s own name is always highly pertinent.

Figure 1.2 Broadbent’s filter model of attention