eBook - ePub

Britain At Work

As Depicted by the 1998 Workplace Employee Relations Survey

Mark Cully, Andrew Oreilly, Gill Dix

This is a test

Share book

- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Britain At Work

As Depicted by the 1998 Workplace Employee Relations Survey

Mark Cully, Andrew Oreilly, Gill Dix

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Britain at Work presents a detailed analysis of the 1998 Workplace Employee Relations Survey, the largest survey of its kind ever conducted.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Britain At Work an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Britain At Work by Mark Cully, Andrew Oreilly, Gill Dix in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Betriebswirtschaft & Business allgemein. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

This book presents an up-to-date portrait of the diverse nature of employment relations in the workplace in contemporary Britain. It does so through the 1998 Workplace Employee Relations Survey (WERS 98), a large and complex edifice constructed to collect, collate and classify what might otherwise remain disparate and diffuse. In this introductory chapter we give a short account of how the survey was carried out, setting it in the context of the times in which it took place.

The worth of this project might best be illustrated by the fact that it is the fourth time the consortium of government, executive agencies and research bodies has joined together to fund it. The first was conducted in 1980, with further surveys in 1984 and 1990. Costly they may be, but there is a demonstrable need to periodically update our stock of knowledge about employment relations at the workplace. We need to be able to say, with reasonable accuracy, what proportion of workplaces (and employees) might be affected by government initiatives, whether innovations have taken root, whether change has occurred, how widespread good practice is, and whether the findings of sector or organisation-based studies can be generalised from the particular to the whole.

Besides this need to replenish our knowledge base, it must also be renewed. Since 1990 many of the issues confronting practitioners and policy makers have altered. In place of concerns over ‘macho’ management and searching for human resource management, most commentators are now interested in the constellation of management practices and whether they cohere into identifiable sets. It is also now well-established that the British labour market and many firms are highly flexible—debate now centres on how this meshes with employment standards and how individuals preserve their ‘employability’. Unions have responded to declining membership by reviewing their approaches to serving members at the workplace.

The 1998 survey is well-placed to measure the new: the subject matter is more wide-ranging and the scope of the survey has been broadened to include very small workplaces and, also, a fresh employee perspective. One change that should be highlighted from the start is the title of the survey. Previous surveys are referred to as the Workplace Industrial Relations Survey (or WIRS for short), but now ‘employee’ has been substituted for ‘industrial’. This change was made for two reasons. First, in approaching workplace managers to take part in the survey, they were told it was a survey of ‘employee relations practices’ (as, indeed, were managers in all past surveys). We decided that to be consistent we should persist with this title. Second, we considered ‘employee relations’ to be a better reflection of the content of the 1998 survey.1 In general, we make only passing reference to the survey title, and mostly use the more general term ‘employment relations’. Irrespective of the title, it should be apparent from the structure of the survey and the content of this book that pluralism has been a guiding motif.

The series to date has attracted some criticism, most notably (and ironically, as he pioneered workplace surveys in Britain) by McCarthy (1994:321). According to McCarthy, the surveys are ‘unlikely to provide us with much more than limited monitoring of changes that we already know about’. The subject, he says, ‘cries out for a case study approach’ as only this is capable of yielding ‘imaginative insights’. Such criticisms have often been applied to surveys: forty years ago Wright Mills (1959) warned of the problems of what he called ‘abstracted empiricism’, which to his mind constituted a ‘withdrawal from the tasks of the social sciences’, and produced results that ‘no matter how numerous, do not convince us of anything worth having convictions about’. We see the position of McCarthy as a retreat into methodological nihilism. Surveys are an essential part of social enquiry, capable of generating new insights and validating old ones, as well as providing a focus for future case studies.

This volume constitutes our primary analysis of the 1998 survey.2 We hope that it satisfies the objective set by the consortium’s Steering Committee for a book which would inform government policy development, as well as stimulate and inform debate among employers, workers and the wider community. The survey will continue to enrich and enhance our understanding of employment relations through secondary analysis of the data, which is publicly available for all to use. And we trust that in-depth case studies will help to establish the conditions under which the statistical associations we have found arise.

The social, economic and political landscape in 1998

Chapter 10, which uses the 1998 survey and its predecessors to quantify the extent of change in employment relations over the past two decades, provides an overview of the main changes to the social, economic and political landscape over the period. In this section, our purpose is to give a short account of the topography at the time of the conduct of the 1998 survey.

In 1998, Britain was at the tail end of an economic upturn that had begun in 1992 following the substantial devaluation of sterling that occurred after exiting the European exchange rate mechanism. There were more Britons in paid work in 1998 than ever before and unemployment (as measured by the claimant count) was at its lowest level since 1979. Inflation was low, the underlying rate running between 2.5 and 3.2 per cent, more or less in line with the target set for the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee. Growth in average earnings, while above inflation, was also relatively modest, running between 4.3 and 5.7 percent. Industrial action in 1998 was rare indeed with only 12 days per thousand employees being lost in the year, less than 1 per cent of the average level in the late 1970s.

Given such circumstances, one might conclude that it was a time when employment relations and working life were relatively trouble-free. There were, however, undercurrents of disquiet. Unemployment still remained high—around 1.8 million were actively seeking work—much of it concentrated in some cities and regions. There were several high profile large-scale redundancies in 1998. Many commentators pointed to evidence of heightened job insecurity. Almost one in twelve workers were in jobs of a temporary kind. Many people were working very long hours—13 per cent worked in excess of 48 paid hours a week, a higher proportion of employees than any other country in the European Union. Allied with concerns about long working hours on people’s health, the consequences of work on life outside the workplace also came to the fore.

As if to symbolise this disquiet, there had been several recent enquiries conducted by august bodies into work and working life. The Council of Churches for Britain and Ireland conducted a major study into unemployment and the future of work, the Royal Society of Arts set about redefining work, and the Fabian Society sponsored a royal commission style investigation into the changing character of work. Research foundations also made more funds available to study the future of work. It may have been a bout of pre-millennial fever, but the nature of work was on the political agenda in a way that had not been so for many years.

Part of the prominence of debates over the nature of work might be traced to a change in the political climate. Indeed, it is tempting to see 1998 as a distinctive year, coming as it did only months after the advent of a new Labour government some 18 years after that party was last in office. This is especially so in the field of employment relations because of the flurry of legislative and other activity which the new government brought to this area. Working time regulations were introduced and steps were taken to establish a national minimum wage. A range of proposals were announced in the 1998 Fairness at Work White Paper (Department of Trade and Industry, 1998a) to extend the coverage and range of individual employment rights, allow for a statutory union recognition procedure, and encourage new ways of working through a Partnership Fund. With one minor exception though,3 none of this new legislation was enacted until after the survey had been conducted.

That is not to say that, in some areas, there had not been adjustments made in anticipation of new legislation, or wider changes to practice in keeping with the new government’s espousal of partnership at work. For example, a study conducted for the Low Pay Commission in early 1998 showed some organisations to be revising pay structures to give above average pay increases to those at the bottom of the scales (Incomes Data Services, 1998). Similarly, a survey of trade unions suggested that prospective changes to legislation had led to a perceived increase in the number of recognition deals throughout 1998 (Trades Union Congress, 1999). Several new partnership agreements were also well publicised, like that between Tesco and the Union of Shop, Distributive and Allied Workers (USDAW). However, one should not overstate these adjustments. The scale of changes made in advance of new legislation was probably modest.

Thus, 1998 may or may not have marked a distinctive break from the past in the arena of employment relations. That is for future historians to judge. What can be said with certainty at this stage is that WERS 98 represents a benchmark against which the legislative changes introduced can be assessed. It is also clear, looking backwards, that the landscape in 1998 differed markedly from 1980. In preparing for the 1998 survey we recognised that so much had altered in British employment relations since the series began that it was time to re-consider the issues which informed the structure of the survey and the design of the questionnaires.

Our approach was to ensure that there was sufficient continuity to map the core features of workplace employment relations and changes in them over time, but beyond that to use the survey to address several themes. These were to:

- examine the state of the contemporary employment contract;

- explore how employee relations and practices at the workplace impact upon its performance and competitiveness; and

- assess whether there has been a transformation in workplace employment relations in Britain.

The first two themes are covered in this book, notably in Chapters 7 and 8 (the employment contract) and Chapters 6 and 12 (workplace performance and employment relations climate). Change is the subject of Chapter 10, and constitutes only an initial analysis of this topic, which is given a more detailed treatment in Millward et al. (2000). Reporting on the ‘core’ of the survey constitutes the bulk of this book. Discussion of the topics under investigation, together with a more specific exposition of the main issues confronting practitioners, policy makers and researchers in the area, is left to the individual chapters. Before proceeding to the analysis it is necessary to give a short account of how the survey was designed and conducted. A fuller, and more technical, account is given in the Technical Appendix.

Design of the survey

Trivial though it may seem, we need to begin by explaining what is meant by a workplace survey. There are two elements to this. First, the basic analytical unit is a workplace, which we defined as ‘the activities of a single employer at a single set of premises’. A branch of a bank or high street store are workplaces in their own right, as are the head offices of those organisations. Workplaces are subsets of organisations, except where the workplace is the sole one in an organisation and it is only here that the terms ‘workplace’ and ‘organisation’ are interchangeable.

To enumerate employment relations in the British workplace, we needed to generate a statistically representative sample of workplaces. One approach, the basis for a recent American study (Kalleberg et al., 1996), is to generate a random sample of employers by asking a random sample of employees for details of whom they work for. This approach has elegant statistical properties (Parcel et al., 1991), but is fraught with practical problems, notably in getting sufficiently detailed and accurate information from workers about their employers.4 In Britain we are fortunate in having a ready-made sampling frame of workplaces: the Inter-Departmental Business Register (IDBR), held by the Office for National Statistics. This register contains details on all going concerns (both privately-owned and publicly-owned) operating in the UK by accumulating details from PAYE and VAT registrations. It is hierarchically organised with its basic ‘local unit’ conforming to our own definition of a workplace in all but a very small proportion of cases.5

Second, a workplace does not speak with a single voice, but with a Babelesque din. The problems confronting the survey researcher in wishing to analyse the workplace are akin to that of studying households: are all members surveyed or just one, and if just one then who should it be? Many household surveys overcome this problem by only interviewing the ‘head’, who speaks on behalf of the household. Our solution was analogous. We identified certain people within the workplace who, by dint of their position, could speak for the workplace. The two respondents were the manager at the workplace with day-today responsibility for personnel and employment relations matters, and a senior worker representative. However, although it was mostly personnel managers and union representatives who were interviewed, it was not a survey of them but of their workplaces. That is, the respondents acted as informants of what went on in their workplace, and they were chosen because of the role they occupied within the workplace.6 In addition, however, and for the first time in the series, we directly surveyed a number of employees within each workplace irrespective of their position within the workplace— this innovation is discussed in more detail below.

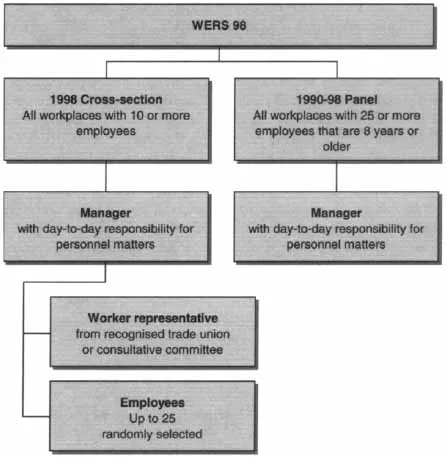

The basic structure, then, was the same as the others in the series: a sample survey of managers and worker representatives in their roles as informants answering questions about the state of employment relations at their workplace. Figure 1.1 summarises the main elements of the survey structure. As can be seen from this, while we have used the term ‘survey’ in the singular throughout, the project consisted of two distinct elements totalling four distinct surveys, three of which (i.e. the 1998 cross-section) are linked.

The 1998 cross-section

We refer to the main element as the 1998 cross-section, which is representative of all British workplaces with 10 or more employees (with some minor exceptions).7 Previous surveys had an employment threshold of 25 employees. This had been seen as the limit below which it would not be possible to easily administer a structured survey, in situations where the employment relationship is often characterised by a high degree of informality (Scase, 1995). Uncovering and measuring informal rules is a major challenge for survey research. Early piloting work showed that it was possible to administer the survey in workplaces with as few as 10 employees.

Dropping the size threshold to 10 employees has the paradoxical effect of increasing the heterogeneity of the survey population while reducing the variability within it. This is because there are as many workplaces with between 10 and 24 employees as there are with 25 employees or more. If we opted to present results for all workplaces with 10 employees or more, we would have had to qualify a large proportion of the findings by noting that they were mostly a feature of very small workplaces. We did not wish to do this. Given this, and for reasons of consistency with past surveys in the series, most of this book is limited to analysis of workplaces with 25 employees or more. In Chapter 11 there is a separate treatment of small business employment relations where the sample of workplaces with 10 to 24 employees is drawn upon.

Figure 1.1 Structure of the survey

As already noted, the IDBR was used to select the sample. The IDBR was first stratified by workplace employment size and by industrial activity. Workplaces were randomly selected within a particular category of size band and industry (e.g. education workplaces with 100–199 employees). Across the sample as a whole, however, larger workplaces were given a greater chance of being selected than smaller workplaces to enable comparisons to be made between them. Similarly, workplaces within some industries (i.e. those with relatively few workplaces, such as electricity, gas and water) were given a slightly greater chance of being selected than those in other industries to allow comparisons across all major industry groups. The variation in the probability of selection of workplaces has been corrected for by weighting the data so that its size and industry profile after weighting matches that of the IDBR. A fuller account of the sampling design and weighting is given in the Technical Appendix.

For the cross-section the intention was to survey around 2,250 workplaces, to be split between 2,000 workplaces with 25 or more employees—roughly the number included in each of the previous surveys—and 250 workplaces with between 10 and 24 employees. In each workplace selected, an interview was to be conducted with the manager who had day-to-day responsibility for personnel matters. There were then two further aspects of the cross-section—the worker representative interview and the survey of employees. They are displayed beneath the management box in Figure 1.1 because we were dependent on management: first, to identify eligibility in the case of worker representatives; second, for permission to interview worker representatives and to survey employees; and, third, to provide the information necessary to contact them.

A workplace was defined as having participated in the survey so long as a management interview was conducted. The next sectio...