1 The delimitation of the country at the end of the Ottoman period

Where is Palestine?

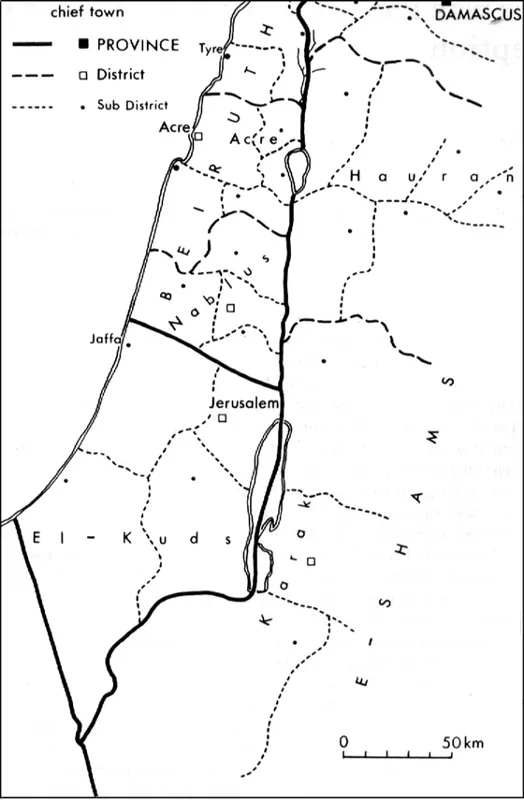

Palestine, with its many names and titles – Holy Land, Eretz Israel, Terra Santa, Filistin – was well known to those who dealt with the subject. These names appeared, among others, on different maps that were printed in the beginning of the period under discussion, the late Ottoman period, without any apparent delimiting definitions of its area. Even though official Ottoman documents that dealt with the numerous issues regarding the land used the name Filistin, they did not mention any defined administrative expression of a confined area called by this name, or by any other name. The administrative system of the Ottoman regime had been in turmoil throughout the nineteenth century. The year 1873 saw the final arrangements that delimited the area between the Ottoman authoritative units in the western Palestine area. Excluding minor changes, these arrangements remained stable until World War I. The area that stretches west from the Jordan river was split between three major administrative units. The northern part of Palestine, from a line that connects the area north of Jaffa, to north Jericho and the Jordan, belonged to the province (vilayet) of Beirut. This district was divided into the province-district (sanjak) of Beirut (containing the counties (qaza) of Beirut, Sidon, Tyre and Marj-Ayoun), Acre (with the counties of Acre, Haifa, Safed, Nazareth and Tiberias) and Nablus (with the counties of Nablus, Jenin and Tul- Karem). The special district of Jerusalem lay to the south of the district of Beirut. Its southern boundaries were unclear, and they coincided with the edge of the settled area in the south of the country.1 The area contained by this district was enlarged following the construction of Beersheba in 1900 and the expansion of Ottoman rule into the central Negev (desert of southern Palestine). It was now bordered by a line that went from the south of the Dead Sea to the north of the Machtesh (crater) Ramon, to the line that was determined in an agreement with Britain, in 1906 (see below). The majority of the central and southern Negev belonged to the province of Hijaz, which also included the Sinai Peninsula, the area east of the Arava, and the western part of the Arabian Peninsula.

Figure 1 Palestine, 1914.

An intention of adding the areas lying east and west of the Arava, from the south of the Arnon stream (Wadi al Mujib) to the Gulf of Aqaba to the province of E-Shams was suggested prior to the outbreak of World War I. This intention, though, was not carried out in practice.2 The Ottoman regime had not specified a special district for Palestine (or Arzi-El- Mukadsa, the Holy Land in Turkish), and the area of Palestine was divided among broader districts that had their centres away from it. As far as the Ottoman regime was concerned, Palestine was an abstract concept that related to a general region, but did not define any clear territorial unit. This unclear situation characterized the regime throughout its ruling period. The Ottomans created a special administrative unit, Mutasarif El Quds (Special District of Jerusalem) which was directly subordinate to the empire’s capital. They also determined accurate borders for this district at the beginning of the twentieth century.3 Anyhow, it remained unclear as to whether this unit is the ‘Filistin’ they were referring to when they discussed Palestine, or whether this special district is only a part of it. This confusion was also apparent in their dealing with the renewed settlement of the Jews in Eretz Israel. In reaction to the renewal of Jewish immigration during the 1880s, the Ottoman regime isued new orders and laws that were intended to limit immigration, land purchasing and settlement. These orders were sent to the countries from which the immigrants had arrived, and to their diplomatic representatives in Palestine, but not directly to the immigrants. Nevertheless, it was the Jewish world, at which these prohibitions were aimed, that went on with discussing the matter. Several newspaper publications, letters and documents reveal that neither the Jews nor the Ottomans had any clear idea about the territorial extent of the immigration decree. The authorities that tried to avoid the Jewish settlement in Palestine were willing to receive Jews in any of the empire’s other regions, but it remained unclear as to where it was permissible for Jews to immigrate to. The situation created by the administrative system led the immigrants occasionally to assume that the immigration decree referred only to the district of Jerusalem, while at other times it seemed to them that it referred to all the area west of the Jordan river.4 As the immigration was being restricted at the beginning of the 1890s, the Jewish newspaper Ha’or published an article in which it was written that the authority’s order is that it is forbidden to aid the Jews in settling in Jerusalem following the Ziara (pilgrimage). Since it is forbidden for them to settle in this district, any of them that wish to settle in the empire’s other lands must address the authorities so it can point out a land in which to settle.5 This limiting attitude, that identifies the expression ‘Fil-istin’ to the district of Jerusalem alone, is also apparent in Lawrence Oliphant’s letter, written ten years earlier in 1882.6 He claimed that by the name Palestine the Ottoman authorities are referring to Jerusalem and its surroundings, but the Mediterranean coast, Samaria, Galilee, the northern valley and the Jordan valley are all called ‘Syria’ and therefore, the consul’s published declaration is only in regard to Jerusalem and its surroundings. This limiting attitude was further broadened with the advice of the Jewish Hamelitz newspaper, that in 1891 told the immigrants that

it is good to settle beyond the Jordan, where the land is vacant, pristine and inexpensive . . . because the entrance to the Holy land has been hindered . . . let us hope that they refrain from seeking themselves an estate in Judea and in Galilee – and that they will turn to Trans-Jordan, and without a voice and without a racket, they will hit roots and blossom.7

Ze’ev Wisotzky, Hovevi Zion’s Palestine correspondent, writes in 1888 that: ‘It is true, Galilee too is included in the decree.’8 A return letter that was distributed by the Hovevi Zion headquarters in Warsaw states that: ‘The government’s warning was not given only about Judea, or about Galilee.’9 The Ottoman regime could not define the borders of the immigration prohibition, and, when coming to enforce it, referred to any point in which Jews were trying to construct an agricultural settlement. Haim Margalit Klaverski, one of JCA’s leaders in Galilee, claimed while discussing the subject of delimiting Eretz Israel’s northern boundary after World War I that the Ottoman government regarded the region of Sidon, with Rashia, Marj-Ayoun, Hasbaya, the Golan and the Houran, as a part of Filistin. He explained that this was the reason it was forbidden for Jews to purchase land in these parts, unlike the situation in the more northern regions of Damascus, Homs and Hamma.10

The unsolved situation regarding the limits of Eretz Israel troubled the country’s Jewish population that began discussing the issue thoroughly. The delimitation of Eretz Israel, as was presented by the Jewish scholars, is a complex subject. The traditional Jewish research, which continues in our time, deals mainly with the historical, religious-based, territorial identity of the land.11 This Jewish research is trying to clarify the territorial meaning of the definitions quoted by the religious tradition, such as ‘the boundary of the area promised to the Patriarchs’, ‘the boundary of those who came out of Egypt’ or the ‘boundary of the returnees from Babylon’. The Jewish Halacha (religious law) had determined a whole set of laws that refer to Eretz Israel, and these laws are limited by the land’s boundaries. The laws include a range of Doings that are connected with Eretz Israel, as well as prohibitions, permits and customs that are treated in one manner within Eretz Israel, and in a different manner outside its boundaries. Jewish law recognizes a number of delimitation options of Eretz Israel, and each one has laws that are attached to it. The need to transfer names and terms from past delimits on to new and contemporary maps created several alternative boundaries to the Jewish religious-based Eretz Israel, each of which correspond to the various terms and commentaries that were given to them. It is true that according to the tradition God’s promise is never cancelled and the area of the promised land is not altered following exiles and other changes. Nevertheless, the Jews have adapted to the political boundaries of the land in keeping with Jewish law during most of the time. The new Jewish settlers in Eretz Israel found themselves struggling with daily difficulties concerning the land’s boundaries. Beyond the general ambition to establish them all over Eretz Israel, the new settlers, who were mostly traditional Jews, tackled numerous religious problems. The Jewish farmers needed to know if the law of the Shmitta (fallow year) should be kept, and which villages should be doing so. They wondered whether the Bikkurim (first fruits), and the Ma’asrot (tithes) should be delivered, and should they celebrate the second Yom- Tov (religious festival) associated with the Diaspora. The immigration to Eretz Israel had imported a problem concerning the laws of matrimony. Religious law supports a Jew in leaving his or her home and moving to Eretz Israel. If the partner refuses to join the move, it is enough of a reason to get divorced. This too, exemplifies why the boundaries of the Halacha-based Eretz Israel needed to be defined. Most of the practical laws were delimited by the traditional ‘limit of the returnees of Babylon’. This limit poses a territorial difficulty as it excludes (and still excludes) regions and places that are usually included in Palestine such as Ashqelon, Gaza, Baisan, Semah, the area north of Acre, and more. A problem of this type arose with the establishment of Bnei-Yehudda, to the east of the Sea of Galilee, and the local inhabitants eventually turned to the rabbis in Jerusalem, and asked them if they should celebrate a second Yom-Tov of the Diaspora.12

The Lovers of Zion and the members of the Zionist Organization could not accurately define the land’s boundaries. The publicist and leader of the Jewish farmers in Palestine wrote that: ‘Israel’s resurrection on Eretz Israel’s land will be done by purchasing all that area that stretches east from the eastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea, and which is termed “Eretz Israel” in the Chronicles.’13 The definition of the historian and educator Ze’ev Ya’abetz was slightly sharper:

the main part of Eretz Israel is west of the Jordan . . . but stronger is its inclination to the land east of the Jordan, the land between the Yarmouk and the Yabok . . . east of the Jordan, stronger is it inclined to the Golan in the Bashan, north of the Sea of Galilee . . . it is allowed, as I think – to tell of the qualities of the land of Gil’ad.14

(translated from the poetic Hebrew of the late nineteenth century)

The Zionist politician and writer Nahum Sokolov determined in his book Pleasant Land: ‘the land of Canaan, from the Mediterranean Sea to the Jordan, and from Sidon to Gaza in the south-west, and to the Dead Sea in the southeast’.15 Another quote from the same book states: ‘An independent Palestine . . . south of the line that that originates from the south of Tyre, and that goes eastward to the Hermon slopes, from Dan to Beer-sheba and the land of the northern Jordan.’ According to Sokolov’s opinion, Eretz Israel is limited to the area west of the Jordan river, and down to the Gaza–Dead Sea line. The members of Hovevi Zion (Lovers of Zion), who were living in Palestine, had a different view of the situation. In an internal discussion it was said that: ‘It is wise to settle many of the craftsmen in the other towns of the holy land, in Nablus, Jenin, Salt (east of the Jordan) Ramla, Gaza and Lydda’.16 These expressions, which were not made during a political discussion over the future of the territories, show the lack of a clear picture, and the confusion that prevailed among those who handled the task of settling the land. Jewish scientific publications of that time were unable to deliver a better and more unite description. Even though most of the people that dealt with Eretz Israel– Palestine refrained from accurately defining its boundaries, some dealt with it. The Jewish Encyclopedia that was published in Russian in St Petersburg in 1910 described Eretz Israel as the area that lies between latitudes 31° N and 33°20 ' N, and between the sea and the Jordan, and longitudes 34°15' E to 35°35' E. According to this publication, the area east of the Jordan, between the Arnon stream, and the Bashan (some 4,000 square miles) was also a part of Eretz Israel. In another Jewish encyclopedia that was published in English in London and New York, there appear two lines that border Eretz Israel. The bottom one goes from the south-eastern corner of the Mediterranean Sea through the southern point of the Dead Sea, and the upper line from Tyre to the southern slopes of Mount Hermon.17

A different way of defining Eretz Israel’s modern area is found in a geography book that was written in Hebrew at the beginning of the twentieth century. This book18 deals with The Geography of the Turkish Empire. It defines Eretz Israel as the area which lies

south of the imaginary line that passes along the Qasamia river, across the Ayoun valley and Marj-Ayoun that belong to the village Metulla, and across Mount Adhear that rises between the Hula and the Lebanon valleys. From there the line will turn towards the southern slopes of Mount Hermon, and reach Mount El-Mani that separates the valley of Damascus from the Houran. The eastern boundary is the edge of the desert, and the southern one goes beyond Wadi Arish, Wadi Abiq, Wadi Mara and Wadi El-Fukra’a.

Summarizing, this shows that according to this book, Eretz Israel is situated between latitudes 30° N and 33°30' N, and longitudes 34° E to 37° E.The image that is reflected by Jewish publications at the end of the nineteenth century is that Eretz Israel spreads out from the Mediterranean Sea (from Rafah in the south to Sidon in the north) to the desert on the east side of the Trans-Jordanian Highlands. There are those who slightly extend the southern line to the edge of the district of Jerusalem, and others that reduce this area in the north and restrict the country by the lower Litani river line. Generally speaking, the Jews remained loyal to the biblical tradition that proclaims ‘from Dan to Beersheba’.

The confusion about Palestine’s delimitation prevailed among Europeans and Americans too. Representatives of European and other countries were involved in the process of determining Palestine’s political boundary, from the nineteenth century to the present time. Europeans, especially the British and French, were the ones who, in different periods, determined the land’s boundaries, which explains the importance of their images regarding Palestine’s delimitation. It is difficult to point out a national image – especially on a background of hundreds and thousands of publications, expressions and statements that dealt with Palestine. Nevertheless, a general directing line can be extracted from examining atlases, maps and encyclopedias19 that were published during the period that preceded the first determinations of Palestine’s boundaries. These sources focused mainly on the land’s past. Even the descriptions of conditions at the time of publication had nothing to do with delimiting the land, or with defining its area as a basis for discussing current geographic processes and facts. Many publications do not treat the subject at all, while others include a vague and general description (‘from the sea to the desert and from the mountains of Lebanon to the southern desert’). Others adopted the Ottoman administrative division as the existing borders. Delimitation of the land according to the Ottoman administrative borders is mainly apparent in German publications starting by the mid-nineteenth century and leading up to World War I.

The detailed description that appears in the Encyclopaedia Britannica demonstrates the blur that surrounded the issue, by this description: ‘Palestine is an abstract geographical name.’ To fulfil its duty, the encyclopaedia defines Palestine in these terms:

Palestine can be thought of as extending from the Litanni’s mouth, 33°20 'N, to the mouth of Wadi Gaza and its continuation towards Beersheba, at 31°28 ' N. The problem is more complicated in the east. The Jordan is not a boundary and it only separates eastern Palestine from its west. It seems that the logical boundary should be the pilgrimage route from Damascus to Mecca. The area east of the Jordan is confined between the Hermon and the Arnon.20

French publications reflect a slightly different image t...