![]()

1

The nature of a crime

Actus reus

Causation

Omissions

Mens rea

Intention

Recklessness

Negligence

Strict liability

Transferred malice

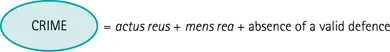

A crime is conduct which has been defined as such by statute or by common law. To be convicted of a crime, two essential elements must be proved:

1 The Actus Reus – the prohibited act, omission, or state of affairs; and

2 The Mens Rea – the required state of mind, such as intent or recklessness.

The actus reus and mens rea vary from offence to offence. Every time you deal with a criminal offence you need to break it down into what needs to be proved for the actus reus and what needs to be proved for the mens rea.

The main exception to this is crimes of strict liability, discussed below.

The prosecution must prove the existence of the actus reus and mens rea beyond reasonable doubt. This is sometimes referred to as the Woolmington rule (Woolmington v DPP [1935]).

GENERAL PRINCIPLES OF CRIMINAL LAW

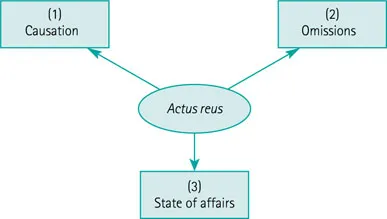

See diagram on facing page.

CHARACTERISTICS OF AN ACTUS REUS

Definition

The actus reus consists of all the elements in the statutory or common law definition of the offence except the defendant’s mental element. It consists of everything that the prosecution needs to prove except the mens rea.

General principles of criminal law

Analysis of the actus reus

The actus reus can be identified by looking at the definition of the offence in question and subtracting the mens rea requirements, which is usually denoted with phrases such as ‘knowingly’, ‘intentionally’, ‘recklessly’, ‘maliciously’, ‘dishonestly’ or ‘negligently’.

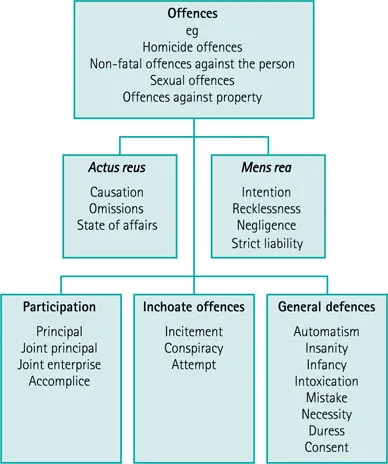

The actus reus states the conduct or omission required for the offence, the specified surrounding circumstances in which it must take place and any consequences if required by the offence.

This process of identifying and analysing an actus reus can be illustrated in relation to s 1(1) of the Criminal Damage Act 1971, which provides:

A person who without lawful excuse destroys or damages any property belonging to another intending to destroy or damage any such property or being reckless as to whether such property would be destroyed or damaged shall be guilty of an offence.

Once expressions relating to the mens rea requirements of intention or recklessness have been subtracted, the actus reus consists of destroying or damaging property belonging to another:

Conduct = the act of destroying or damaging

Circumstances = the fact that the property must belong to another

Consequences = the resultant damage or destruction

CONDUCT AND RESULT CRIMES

In analysing the actus reus, it is possible to distinguish between ‘conduct’ crimes and ‘result’ crimes. Conduct crimes punish the actual conduct of the defendant. An example of a conduct crime is perjury. The offence is committed where the defendant makes a statement on oath which he knows to be false or does not believe to be true (s 1 of the Perjury Act 1911). The making of such a statement is sufficient to establish the actus reus. The consequence of the statement is irrelevant. It does not matter whether his statement is believed or not.

By contrast, result crimes punish the consequences of the defendant’s actions. In a result crime the actus reus requires the prosecution to prove that the defendant’s conduct caused a particular consequence. An example of a result crime is murder. It must be proved that the defendant caused the victim’s death. As we have seen, s1(1) of the Criminal Damage Act 1971 is a result crime. The actus reus is that the defendant caused damage to, or destruction of, property belonging to another.

SPECIFIC ISSUES IN ESTABLISHING THE ACTUS REUS

(1) CAUSATION

The question of causation only applies in relation to result crimes. We have seen that result crimes require the prosecution to prove that the defendant’s conduct caused a particular consequence. Issues of causation do not arise in ‘conduct’ crimes since they are not concerned with the results and consequences of the defendant’s conduct.

Two different forms of causation need to be established:

1 factual causation;

2 legal causation.

Causation is helpfully illustrated in relation to murder. As we will see, part of the actus reus of murder is that it must be proved that the defendant caused the victim’s death.

Factual causation

The first step in establishing causation is to ask ‘was the defendant’s act a cause in fact of the specified consequence (for example, death in the case of murder)?’. This question can be answered by asking: ‘But for what the defendant did would the consequence have occurred?’ If the answer is no, causation in fact is established.

An example of where the prosecution failed to establish causation in fact is the case of R v White [1910]. The defendant had put cyanide into his mother’s drink, but the medical evidence showed that she died of heart failure before the poison could take effect. Consequently, the answer to the question ‘But for what the defendant did would she have died?’ is ‘yes’. She would have died anyway.

Legal causation

Just because the prosecution establish that the defendant’s act was a cause in fact of the prohibited consequence, does not necessarily mean that the defendant is liable. The prosecution must establish a legal chain of causation between the defendant’s acts and the specified consequence. This can become difficult where other individuals or events also contribute to the prohibited harm.

The defendant’s act must be a ‘substantial’ cause of the consequence in question (R v Cato [1976]).

It should be noted that ‘substantial’, in this context, simply means anything more than a de minimis (trivial) contribution. For example, in R v Hennigan [1971] it was held that the defendant could be found guilty of causing death by dangerous driving even though he was only 20 per cent to blame for the accident.

Also subsequent events must not have broken the chain of causation. An intervening act by the victim will not break the chain of causation unless it is free, deliberate and informed. In R v Roberts [1971] the victim jumped from a moving car after the defendant had sexually assaulted her. He claimed that she had broken the chain of causation. The Court disagreed. He was guilty of actual bodily harm (ABH) because her actions were not free, deliberate and informed. Compare this decision with R v Kennedy [2007].

An intervening act by a third party will not break the chain of causation unless the act was not a foreseeable consequence of what the defendant had done. In R v Pagett [1983], the defendant used his girlfriend as a ‘human shield’ and fired at the police. The police fired back and killed the girlfriend. The defendant was found guilty of her death. The police fire had not broken the chain of causation because it was foreseeable that the police officers would return fire on the defendant.

◗ R V KENNEDY [2007]

The legal chain of causation is broken where the victim is an informed adult of sound mind and their actions are free, deliberate and informed.

Facts

The defendant supplied the victim with a class A controlled drug. The victim then freely and voluntarily self-administered that drug and died.

Held

The defendant was not liable for the victim’s manslaughter. The criminal law generally assumed the existence of free will and, subject to certain exceptions, informed adults of sound mind were treated as autonomous beings able to make their own decision on how to act.

The ‘thin skull’ rule

As in tort, the de...