![]()

1

How the Internet Is Changing Journalism, and How It Affects You

All journalism today involves computers. Regardless of whether you write for a newspaper or magazine, an online site, or for a television or radio newscast, you almost certainly will write with a desktop computer or laptop and some form of word-processing package. Computers are also involved in most of the news production process after a story leaves a reporter’s desk. You are also probably using the Internet as a newsgathering tool. But if you are not using it to its fullest capacity, you are ignoring a goldmine of information. Professor Steve Ross formerly of Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism has been tracking the adoption of the Internet by journalists each year since 1996, and by 2002 he concluded Internet adoption was almost universal. By the early years of the new century, Ross said, journalists had embraced the Web and e-mail as reporting tools (Ross 2002: 22–23).

The phrase computer-assisted reporting (CAR) describes this combination of computers and reporting. Any journalist who uses the Internet is doing a form of CAR. Journalism is, after all, about working with information and the Internet is one of the world’s single largest sources of information. The section Journalists and Technology: Some Context and History notes that when journalists first started using telephones, stories were labeled “telephone-assisted reporting.” We face a similar situation with CAR. With time the phrase “computer-assisted” will atrophy, just as the phrase “telephone-assisted reporting” has become redundant. CAR is about using technology to help gather better quality information to produce better quality reporting. Any journalist younger than 30 probably takes computers for granted. They are the first generation to have been surrounded by computers during their high school years. The Internet is now as common and available to high school and university students as the encyclopedia and library were to earlier generations.

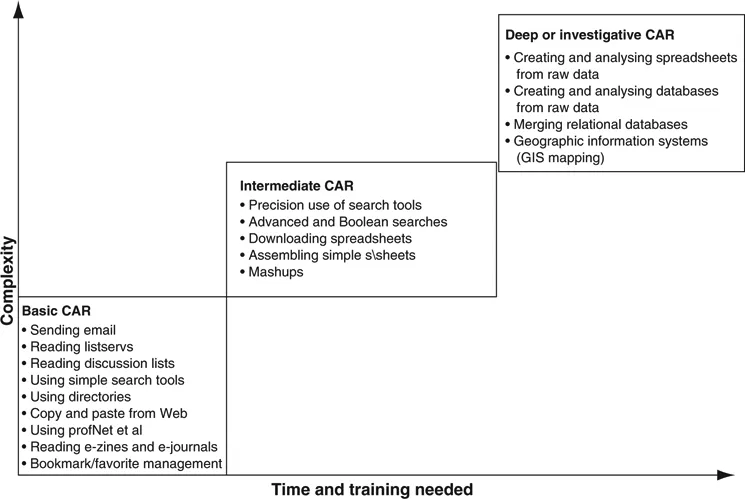

This book reserves the phrase deep CAR for a sophisticated form of reportage that involves analysis of spreadsheets, databases, and other high-end software packages. We believe that deep CAR is one of the most important new tools available to journalists, and we dedicate the last chapter to it. Figure 1.1 describes the levels of CAR as they are applied in this book. Perhaps it is because the authors started with manual typewriters and dial-up phones, and initially accessed the Internet via slow modems rather than broadband that we appear so pedantic.

Figure 1.1

This book is about learning skills to make you a better journalist, regardless of the terminology people have adopted. Professor Philip Meyer, a CAR pioneer who also coined the phrase “precision journalism,” argues that CAR has become so broad that the phrase should be abandoned. He fears that online research, under the mantle of CAR, diverts attention from complex data analysis and other powerful uses of the computer. In the interests of keeping things simple, we will concentrate on the idea of using technology to produce better journalism.

At the turn of the last century, one of the authors wrote that the Internet would “prove to be the most significant human development since Gutenberg’s invention of moveable type in the middle of the fifteenth century” (Quinn 2001: ix). This book acknowledges the massive changes since then, and believes that the Internet will continue to produce more change as we move further into the new century. One of the biggest changes will be the trend toward a multimedia form of journalism, which necessitates a multimedia focus and mindset during the newsgathering process. That is the focus of this book: How to gather good information in the context of an evolving form of journalism that is interactive and incorporates multimedia.

This opening chapter deliberately takes a big picture overview. Those of you who like jigsaws will understand the process. When building a jigsaw the most efficient approach is to establish the outline first, then fill in the middle. That is the purpose of this chapter. It looks at how the Internet is influencing journalism and newsgathering and consider how audiences are fragmenting and how journalists need to change to accommodate those fragmented audiences. We also consider one of the major reactions to fragmenting audiences: the phenomenon known as media convergence. It is both a management and a journalistic change. At the editorial level, convergence represents a new form of journalism that requires new skills. As a business process, convergence is an attempt to reaggregate or regather splintered audiences. People get their news from a variety of sources, at different times of the day. The only way a news organization can reach as large an audience as possible is by offering news via different media at different times of the day. We need to consider the economic environment in which the worlds of media and journalism operate, so we need to consider the changing forms of media economics. This chapter concludes with a short outline of the tools the journalism profession has embraced in its relatively short history.

The Web and e-mail are becoming, as journalism researcher Steve Ross notes, the “soul of newsgathering.” Increasingly the rhythm of the news business “keeps time with the Internet” (Ross 2002: 4). Nine out of ten people who responded to his national survey of American journalists said that the Internet had “fundamentally changed” the way they worked. Slightly more (92 percent) agreed that new technologies and the Internet had made their jobs easier and made journalists more productive (Ross 2002: 27). A study of media students in Australia showed they were more likely to obtain their news from the Web than from printed newspapers. They all used e-mail extensively, researched online rather than with books, and seemingly carried their mobile phones with them at all times (Quinn and Bethell 2006: 51).

This chapter needs to be read in the context of major change within journalism and the world of media. One of the biggest changes is the emergence of convergent forms of journalism. Convergence is also known as multi-platform publishing (in some parts of the world each medium is seen as a platform; thus we have the newspaper platform or the radio platform). Convergence comes in several forms. Editorial staff work together to produce multiple forms of journalism for multiple platforms to reach a mass audience. In many cases the one newsroom produces content for a daily newspaper, radio and television bulletins, online sites, and sometimes magazines and weekly newspapers. Some reporters only work for the newspaper; others only work to produce television news. But some reporters work across media, and others produce interactive content especially for the Web on a 24/7 basis. For the last group, convergence represents a new form of journalism. A converged newsroom has links with traditional media and draws from its history and traditions, but convergence als o requires reporters to produce original content in multimedia forms. This form of journalism is often expensive and time-consuming. For more on this international trend, see Stephen Quinn’s 2005 books in the reading list. Media organizations around the world are merging their newsrooms. An international study in 2002 showed that two out of three media organizations in both print and broadcast have shared their newsrooms with the online team (Ross 2002: 20–21).

Mike Game, chief operating officer of Fairfax Digital, the online arm of what has become Australia’s biggest newspaper publisher, noted how people were turning to the Internet for breaking news. The Internet’s great strength, he said, was its ability to attract people during the day for short news grabs. “In many ways it is displacing more traditional media like radio news services” (quoted in MacLean 2005: 18). In a major research report released late in 2004, the Carnegie Foundation noted that 39 percent of men aged 18–34 got their news from the Internet compared with 5 percent who read newspapers. Women in the same age group preferred local television news (42 percent), compared with 7 percent who read newspapers (Brown 2005: 1–2). In a landmark speech to the American Society of Newspaper Editors in Washington on April 13, 2005, News Corporation chairman Rupert Murdoch cited the Carnegie figures:

What is happening is … a revolution in the way young people are accessing news. They don’t want to rely on the morning paper for their up-to-date information. Instead, they want their news on demand, when it works for them. They want control over their media, instead of being controlled by it (Murdoch 2005).

In response, news has become a 24-hour continuous process, demanding major changes in the way journalists work. To provide unique content for their Web sites, major American newspapers such as The Washington Post, The New York Times, The Chicago Tribune, USA Today, and The Los Angeles Times introduced groups of rewrite journalists on “continuous” or “extended” news desks. The aim is to publish breaking news online as soon as possible after stories become available. These teams function like the rewrite desks that were common in afternoon newspapers until the 1960s. Groups of senior editorial staff at these major newspapers talk to reporters about stories they are working on, or rewrite reporters’ early versions of stories in conjunction with wire copy while events are still unfolding.

The continuous news desk at The Washington Post is based in the newspaper’s newsroom in Washington, DC. The Web site, WashingtonPost.com, is located across the Potomac River in Arlington, Virginia. Robert McCartney, assistant managing editor for continuous news, said a team of three editors and two writers solicited and edited breaking news from reporters in the field—“especially during peak Web traffic hours of 9 am to 5 pm”—and also wrote their own stories. The goal was to increase the flow of original content to the Web, to distinguish The Washington Post coverage from what other papers and the major news agencies produced, McCartney said. Ideally the newspaper’s reporter wrote the early file for the Web. “We want to take advantage of the beat reporter’s expertise, sourcing, and credibility.” When a beat reporter did not have time, the reporter telephoned notes to the desk, where a writer produced a story under a double byline. “This arrangement encourages beat reporters to file for the Web while relieving them of the burden if they’re too busy.” If necessary, continuous news department editors wrote stories on their own, “doing as much independent reporting as possible, and citing wires or other secondary sources.” (McCartney 2004)

Dan Bigman, associate editor of NYTimes.com, said the continuous news desk at The New York Times had been a catalyst for changing newspaper journalists’ opinions about online, and vice versa. “The continuous news desk has changed the culture,” Bigman said. In August 2005 the New York Times Company announced that its print and online newsrooms would merge when the company moved to new headquarters in 2007. Online commentator Mark Glaser suggested this was the beginning of a philosophical change that would echo through the newspaper business. Publisher Arthur Sulzberger, Jr. and the man in charge of NYTimes.com, vicepresident of digital operations Martin Nisenholtz, had been planning the merger for a decade (Glaser 2005).

USA Today started its 24-hour newsgathering service for the Web in December 2005 and The Chicago Tribune followed a month later. Ken Paulson, editor of USA Today, said he hoped the print edition would enhance the online edition, and “those online will help bring their talent to the newspaper.” It was, he said, “a combining of talent.” Charles Madigan, editor of continuous news at the Tribune, said this form of news was his paper’s new primary focus. “We needed some vehicle to provide a constant stream of news to the Tribune Web site.” (quoted in Strupp 2006: 23) Joseph Russin, assistant managing editor for multimedia at The Los Angeles Times, said his paper created an extended news desk to get immediacy on the paper’s website. “The extended news desk takes stories—wire or LA Times reporters’ stories—and rewrites or edits the items and gets them on the website.” The desk allowed the site to get ahead of stories. “We compete with The New York Times and The Washington Post. In order to be more competitive we needed to be more current.” Russin said a strong push for the desk came from national and international reporters who wanted their stories published faster (Russin 2003).

Elsewhere in the world, similar forms of journalism are emerging. The Inquirer is one of the most innovative media groups in the Philippines. J. V. Rufino, editor-in-chief of Inquirer.net, regards his team of 15 multimedia reporters as a “testing lab” for the future of The Inquirer newspaper. All his team are multimedia reporters: They take photographs at news events and shoot video as well as write stories for online. The Web team typically produces about 120 breaking news items a day. Rufino tells his multimedia reporters that they are the future. Meanwhile, a lot of the younger reporters at the newspaper have said they want to get involved with multimedia. In Singapore, a team of a dozen producers assemble content for Straits Times online, mobile, and print (STOMP). STOMP is part of Singapore Press Holdings, the major newspaper company in the city whose flagship is The Straits Times. The newspaper has a Web site that mostly contains content from the newspaper. Much of STOMP’s content is multimedia and focuses on a younger audience (Quinn, personal observation).

These news organizations are innovative. Elsewhere in the United States, we see relatively little original content, based on research from Columbia University’s Steve Ross. More than a quarter of media respondents admitted that less than 10 percent of their Web content was original, while only 13 percent of respondents whose organizations had a Web site said the bulk of their Web content was original. “In general, however, original content—that is, content on the web site that has not previously been broadcast or published in print—seems to be increasing faster for newspapers (from a low base) than for magazines and broadcast.” Ross did note that more newpapers were allowing their Web site to scoop the print publication. “Routine scooping by the web sites has increased greatly in recent years, but [the 2001] jump was the greatest of all: 45 percent of print respondents said the Web site routinely scoops the print publication.” Three out of ten newspaper respondents said they never or almost never allowed the Web site to scoop (Ross 2002: 18–19).

Around the world, print newsroom staff still represents the bulk of any editorial team, because the bulk of advertising still appears in print form. Online numbers remain low relative to total editorial staff numbers. Some examples from Australia help illustrate this point. News Ltd was the country’s biggest newspaper publisher until May 2007, publishing seven daily and seven Sunday newspapers. Its two dailies in Sydney, The Australian and the Daily Telegaph, have more than 700 people on their editorial staff while its online arm, News Interactive, has only about 60 journalists across its range of sites: news.com.au, foxsports.com.au, homesite.com.au, carsguide.com.au, and careerone.com.au. The other News Ltd sites associated with capital city mastheads each had about 10 dedicated journalists, although that number was expected to grow. The Fairfax group became the country’s biggest newspaper publisher in May 2007. Bruce Wolpe, Fairfax’s director of corporate affairs, said the organization had about 850 people on its editorial staff across The Sydney Morning Herald and The Age in Melbourne (Wolpe 2006). But the stable of online s...