![]()

1 Universal design, buildings and

architects

The bottom-up route to universal design

Broadly, universal design means that the products which designers design are universally accommodating, that they cater conveniently for all their users. On the route towards this goal a product that was initially designed primarily for the mass market of normal able-bodied people could have been subsequently been refined and modified – the effect, with accommodation parameters being extended, being that it would suit all its other potential users as well, including people with disabilities.

Five examples of this universal design process are cited, none of the products concerned being ones that in previous forms had been geared to suit people with disabilities. First, the remote-control television operator. Second, the personal computer – as word processor, electronic-mail communicator and, through the Internet, information provider. Third, the mobile telephone. Fourth, the microwave cooker. Fifth, the standard car with off-the-peg features such as automatic drive, central door-locking, electronic windows and power-assisted steering. Good design for everyone, it may be noted, is good for disabled people.

The methodology of this design process is termed bottom up. The comparison is with a product initially designed to meet the special needs of a particular group of people with disabilities, one that was subsequently modified so that it suited normal able-bodied people as well; here the design process would have been top down.

In the case of the five bottom-up examples cited, the extension of accommodation parameters to take in people with disabilities was achieved by virtue of modern technology, most importantly electronic technology. There is not therefore a straight analogy here with the architect, who when designing a building aims to make it universally accommodating and convenient for all of its potential users, since electronic technology cannot facilitate the accomplishment of all the activities undertaken by each and every person who uses a building. But it does, for instance, serve well where automatic-opening doors are installed as normal provision to make it easier for everyone to get into and around public buildings.

The architect who takes the bottom-up route to universal design works on the premise that the building users he or she is serving, including those with disabilities, are all people who can be treated as normal people. The architect does not start with the presumption that people with disabilities are abnormal, are peculiar and different, and that, in order to make buildings accessible to them, they should be packaged together and then, with a set of special-for-the-disabled accessibility standards, have their requirements presented in top-down mode as add-ons to unspecified normal provision.

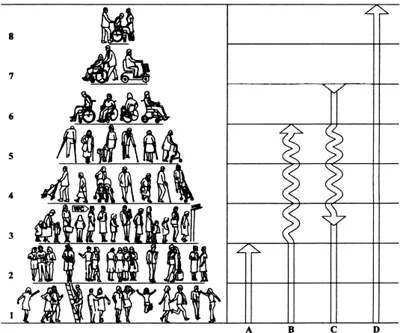

With regard to public buildings, ones that are used by all kinds of people, the route to universal design is illustrated by diagram 1.1 with its pyramid of building users. For a building that is to cater conveniently for the needs of all its potential users, the architect, moving up from one row to the next, looks to expand the accommodation parameters of normal provision, and by doing so minimise the need for special provision to be made for people with disabilities. The aim will be to ensure, so far as possible, that no one will be threatened by architectural disability – from being unable or finding it very difficult to use a building or a feature of it on account of the way it was designed – or (meaning in effect the same thing) be subjected to architectural discrimination.

Against these criteria, judgements are made on how architects have tended to perform over the last fifty years or so, the subjects under review being public buildings such as theatres, department stores, pubs, hotels and restaurants – ones which among their other amenities have public toilets for the benefit of their customers.

In row 1 at the foot of the eight-level pyramid are fit and agile people, those who can run and jump, leap up stairs, climb perpendicular ladders, dance exuberantly and carry loads of heavy baggage. In row 2 are the generality of normal adult able-bodied people, those who, while not being athletic, can walk wherever needs or wishes may take them, with flights of stairs not troubling them. Scoring as at pointer A, architects do as a rule cater well enough for these people. It needs, however, to be noted that there are no small children in rows 1 and 2.

Like those in rows 1 and 2, the people in row 3 are in the main also normal able-bodied people, and in the public realm the architect frequently fails them. These are women, the users of public buildings who when they attempt to use public toilets are regularly subjected to architectural discrimination because the number of wcs provided for them is typically less than half the number of urinals and wcs that men are given, the effect being that they can be obliged to join a long queue or abandon the quest.

In row 4 are elderly people who, although perhaps going around with a walking stick, do not regard themselves as being ‘disabled’. Along with them are people with infants in pushchairs, who – men as well as women – can be architecturally disabled when looking to use public toilets on account of stairs on the approach to them and the lack of space in wc compartments for both the adult and the infant in the pushchair.

In row 5 are ambulant people who have disabilities. Broadly, the building users who are in rows 3, 4 and 5 are people who would not be architecturally disabled if normal provision in buildings were suitable for them, if it were standard practice for architects to design buildings to the precepts of universal design, with public toilet facilities being more accommodating and conveniently reachable, and steps and stairs being comfortably graded and equipped with handrails to both sides. Across Britain, however, that is not by any means a general rule, the effect being as shown in pointer B where the squiggle in rows 3, 4 and 5 indicates building users who could when new buildings are designed be conveniently accommodated by suitable normal provision, but often are not.

The people in row 6 are independent wheel-chair users, and with them Part M comes into the reckoning. In the years since 1985 new public buildings in Britain have had to be designed in compliance with the Part M building regulation, meaning that access provision for disabled people has to be made in and around them. The Part M process operates top-down, and it focuses on making special provision in buildings. It is independent wheelchair users who govern its ‘for the disabled’ prescriptions, and an effect of this when the design guidance in the Part M Approved Document is followed is that the needs of independent wheelchair users may be satisfied, but not necessarily those of ambulant disabled people or people in wheel-chairs who when using public buildings need to be helped by someone else. The outcome of this selective top-down procedure is shown in pointer C, with the squiggle denoting the people in rows 5, 4 and 3 whose needs may not be entirely taken care of when they use public buildings.

1.1The universal design pyramid

The physically disabled people whose particular needs are not fully covered by Part M are at the top of the pyramid. In row 7 are wheel-chair users who need another person to help them when they use public buildings, and those disabled people who drive electric scooters. In row 8, having regard in particular to the usage of public toilets, are wheelchair users who need two people to help them when they go out.

A need that people in row 8 and many of those in row 7 could have when using public buildings would be for a suitably planned unisex toilet facility where a wife could help her husband, or a husband his wife. This would be special rather than normal provision, but for universal design purposes it would be admissible; the rule is that where normal provision cannot cater for everyone, supplementary special provision may be made.

Of the people with disabilities shown in the pyramid, one – in row 5 – is a blind person led by a guidedog. The others, either ambulant disabled or wheelchair users, are all people with locomotor impairments. It is these who when using public buildings are most vulnerable to architectural discrimination, for example on account of steps and stairs, confined circulation spaces, and fixtures, fittings and controls that are too high or too low to reach. And for the architect who is looking to counter architectural discrimination when designing a building on the drawing board or computer screen, it is people with locomotor impairments who can most readily benefit. By way of information conveyed on architectural drawings the scope available to help people with sensory or cognitive disabilities is tiny by comparison.

Ideally, the outcome of applying the principles of universal design would be as shown by the D pointer, indicating buildings that are entirely convenient for all their users. As has already been noted, however, the pyramid does not show children, and for them an important consideration is the height of fixtures and fittings.

The issue is exemplified by wash basins. In cloakrooms in public buildings where there is a single basin, and also where two or more basins are at the same level, it is customary for the bowl rim to be at about 820 mm above floor level. As diagram 4.11f on page 37 shows, this is not convenient for young children. Nor, as diagrams 4.11a and b show, is it convenient for standing adult people, for whom 950 mm is more suitable. There is no single level at which a wash basin can be fixed so that it suits all users.

The principles of universal design are not compromised by it not being possible to fix a wash basin at a height which will be convenient for all its users. By expanding the accommodation parameters of normal provision, with supplementary special provision being added on where appropriate, the architect's objective is to make buildings as convenient as can be for all their potential users. The operative condition is ‘as convenient as can be’. There are times, as with washing at a basin, when architectural discrimination is unavoidable.

The Part M building regulation

Britain's national building regulations are functional – they ask for something such as ventilation, means of escape in the event of fire, drainage, sanitary conveniences and washing facilities to be provided at an adequate or reasonable level. In England and Wales the function that is covered by the Part M regulation is access and facilities for disabled people (in Scotland Part T, the access-for-the-disabled building standard which was the equivalent of Part M, has been assimilated into other parts of the Scottish building regulations). The design standards prescribed in the 1999 Part M Approved Document are shown in many diagrams in this book, and are the yardstick against which universal design options are measured.

For access provision in newly designed public buildings, a narrow interpretation of Part M requirements can for three reasons hinder the realisation of universal design. First, because exclusive attention to the needs of disabled people ignores many other building users who are prone to architectural discrimination, for example women in respect of public toilet facilities. Second, because of the top-down form of Part M: it comes with minimum design standards that present cut-off points, meaning that disabled people who are not accommodated by the minimum standards are liable to be excluded. Third, because of the conflicting methodologies of designing for the disabled versus designing for everyone.

The story of how the Part M regulation came to be introduced is told in Designing for the Disabled – The New Paradigm. It began in the 1950s when Tim Nugent was director of rehabilitation education on the Champaign Urbana campus of the University of Illinois. Many of his students were young paraplegics in wheelchairs, and the task that he set himself was to train them to manage independently, to get around on their own and undertake all the activities of daily living without assistance. Architectural barriers, he recognised, were the obstacle that stood in the way of their being able to realise their full potential for achievement and compete successfully with others for the material rewards that America offered. To set about removing the barriers he drew up the world's first-ever set of design standards for accessibility and then went on to demonstrate how the university and public buildings in Champaign and Urbana could be altered so that they were accessible to wheelchair users. He became America's national expert on the subject, and an outcome of his pioneering work was that he was asked to prepare the draft of what was to be the seminal document in access-for-the-disabled history, the initial American Standard, the 1961 A117.1 American Standard Specifications for Making Buildings and Facilities Accessible to, and Usable by, the Physically Handicapped.

In America, and then in Britain and elsewhere around the world, the 1961 A117.1 set the mould for access standards. It drew on four propositions, which were flawed, but which in the context of the administration of regulatory controls for accessibility have effectively remained undisturbed.

They were first, that architectural barriers in and around buildings are a threat to disabled people, but not to able-bodied people; second, that all disabled people – all those with a physical, sensory or cognitive impairment – can be disadvantaged by architectural barriers and can be emancipated where they are removed; third, that what for accessibility purposes suits wheelchair users will generally serve for all other disabled people, allowing there to be a single package of access prescriptions with a common set of design specifications; and fourth, that design specifications for disabled people can be precise and definitive – that there are ‘right’ solutions.

Following a meeting which Tim Nugent addressed at the Royal Institute of British Architects in October 1962, Britain took up the challenge, and the first British access standard, CP96, Access for the disabled to buildings, was issued by the British Standards Institution in 1967. In one significant respect, toilet facilities for disabled people, its design standards differed from those of A117.1. The American line, in accord with Nugent's determination that wheelchair users ought to be treated as though they were normal people, was that each normal toilet room for men and women in a public building should incorporate a wheelchair facility, a small-size one which was geared to suit capable wheelchair users who could manage independently but not those who needed to be helped – they could be ignored. In Britain research findings had highlighted the lack of public toilets for severely handicapped wheelchair users who needed to be helped by their partner1, and the need was for a design standard for a unisex facility, one that would be set apart from normal toilet provision. A key item in the 1967 CP96, this was an amenity which had never previously been tested in practice, and as feedback from users soon confirmed, the dimensions set for it – 1370 × 1750 mm – were not generous. When CP96 was revised and became BS 5810 in 1979, the design standard for a unisex toilet came with a 1500 × 2000 mm plan layout.

The Part M building regulation followed in 1987, with the guidance in its Approved Document being drawn directly from the BS 5810 access standard, including the advice for a unisex toilet; as is discussed on page 71, this facility is by no means ideal for its purpose. But through the 1990s the 1979 BS 5810 remained in place, and the design standards presented in it, including those for the unisex toilet, were virtually unchanged in the 1992 and 1999 editions of the Part M Approved Document.

With universal design the aim is that buildings should be convenient for all their users, with architectural discrimination being avoided. But as has been noted with regard ...