![]()

Chapter 1

Action Research Explained

This chapter gives an overview to set the scene, then subsequent chapters deal with each issue in a more detailed way. First of all a comprehensive definition:

Action research is an investigation, where, as a result of rigorous self-appraisal of current practice, the researcher focuses on a ‘problem’ (or a topic or an issue which needs to be explained), and on the basis of information (about the up-to-date state of the art, about the people who will be involved and about the context), plans, implements, then evaluates an action then draws conclusions on the basis of the findings.

(Macintyre 1991)

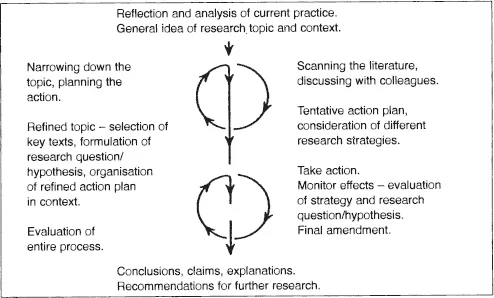

This may be summarised as in Figure 1.1

Figure 1.1 An action research cycle

The research must progress steadily through the stages outlined in Figure 1.1 or nothing new would ever be discovered, but all the time as the action unfolds, there is constant reflection on the ongoing process. This comes through discussing with others, constantly reconsidering and evaluating e.g. the advice taken from the literature, the developing research question and all aspects of the action-plan in the light of the ongoing investigation. This means that in reality, the process is cyclical – it is not straightforward at all.

Implicit in the definition and the figure are the principles which must be followed if the investigation is to merit the term ‘action research’. The first is that the researcher ‘reflects on current practice, and as a result focuses on a “problem” which needs to be explained’. What does this involve?

This may mean re-examining established ways of teaching or classroom procedures, or if there is a gap in present practice, trying something for the first time. It may mean evaluating recommended teaching strategies or different modes of classroom organisation, or experimenting with innovative ways of teaching or taking steps to understand and improve some aspect of the children’s development. There are many, many fascinating possibilities, but the chosen one will concern something from the repertoire of teaching competences that requires explaining, hence the non-critical research use of the term, ‘problem’.

This could suggest that the research was based on the negative premise of ‘having to do something to improve the status quo’, but this is not the case. The fact that extremely busy teachers are prepared to go the extra step to ensure that their practice is as good as it can be, is the real thrust behind classroom research. As has been said, the research process begins with reflection, and this can be very difficult, especially for experienced teachers who have built up a repertoire of successful coping strategies. These have been established through much trial and error and selecting the best personal way, and so it is not easy to review that process critically and make decisions about what new things to try. And yet at the same time these teachers would want to disavow any suggestion that they were entrenched in tried and tested ways. Perhaps the ‘promise’ that trying out new things can re-energise the classroom through bringing a sense of the unknown into play will tempt some who are reluctant? For surely it is these experienced teachers who are the ones who can leave established routines, confident in the knowledge that their teaching will not be threatened? Mclntyre (1993) highlights this difficulty, but endorses the value of reflection. He claims that: ‘learning (for experienced teachers) is dependent on them examining assumptions and considerations which make sense of their actions as teachers: without reflection they cannot change their practice in a controlled or deliberate way.’ This is because so much of their practice is intuitive, i.e. based on long-practised skills. Interestingly, he also explains that reflecting on practice is less difficult for students or inexperienced teachers because in new teaching, ‘every halting step is achieved through conscious control’. This being the case, reflection is a constant ongoing process. Students do not have many ‘advantages’ over experienced teachers. Perhaps this is one?

The next part of the definition, i.e. the one which refers to ‘the up-to-date state of the art’, is a way of describing the second principle, i.e. ‘that both the choice of topic and the way of investigating it, must be informed by recent literature’, and here research journals are particularly fruitful sources of information.

Why is the Literature so Important?

There are several reasons. The first, for those who have difficulty deciding on their topic, is that browsing through the literature can pinpoint a topic which would be both relevant and interesting for the researcher and contextually suitable. Or, by highlighting key words and phrases, the literature can help to focus thinking on particular aspects of a topic and help new researchers realise that a similar investigation could be possible/feasible/realistic in their own context. This can be a great help in getting started.

The next, and this is critically important for all researchers, is that studying and selecting and eventually reporting the literature which has been used, gives the work an academic base. It demonstrates that the researchers have studied developments in the particular field of enquiry and that they will begin their own investigations from an informed stance. This gives everyone confidence, for it shows that what is to be attempted has been carefully considered. Moreover, other researchers may have spent a great deal of time and effort making a similar investigation and it would be inefficient to replicate work when the opportunity is there to extend what has been achieved. In this way new projects can take understanding forward, and this, i.e. ‘research extending knowledge’ (Brown 1990), is what research is all about.

The extension of knowledge depends on the formulation of the critically important research question which emanates from the guidance offered by the literature, i.e. from the experts in the particular field. Framing this question is not easy, for sometimes different authors have conflicting theories, and the new researcher must compare and contrast and evaluate these ideas, then contextualise i.e. envisage how apt they could be for the new investigation, before deciding on the best way forward. Or perhaps the reported research is based on a large-scale study and only snippets can be of use to researchers based in one classroom. And so decisions need to be made as to the most appropriate ways to design the action plan and gather the data. These will be important in ongoing and final evaluations when the researchers will ponder questions such as, ‘Was that the best strategy for my children in my classroom?’, and ‘Did the literature that I selected give me the most helpful advice?’

Another important reason for being guided by the literature is that it can alert readers to potential research difficulties. Quite often, researchers can have really interesting ideas, but not until they go to the literature do they realise the scale and complexity of their envisaged change. This is particularly true if the topic is something like ‘raising the self-concept of pupils’ – a topic which has great appeal for students. Of course this is a laudable thing to attempt, but the literature shows how difficult it is, and how the students, in their short time with the children, could hardly begin to influence other ‘impinging variables’ or in non-research language, influences outside the school over which they have no control but which severely affect the self-concept of their children. In alerting readers to the complexities of their chosen topic, the literature shows how important it is to consider the parameters of the investigation in relation to outside influences and the time-scale available.

Certainly those who intend to write up their research as a thesis must ensure that their topic is not ad hoc, but can be supported by other investigations in the field, for these will have to be carefully selected and critically analysed to show how they have informed the subsequent investigation.

Then the definition asks researchers to consider, ‘the people who will be involved, and the context’, in other words the participants and the place where the investigation will happen. Those who carry out the research have the responsibility of working with children in school who are, to some extent, a captive audience with little power to say ‘no’. And so, all of the time, throughout the preparation and implementation stages, the researchers must consider the suitability of their chosen topic for the children in terms of their age, their stage of development, their attainment, their personalities and possibly their friendship groups. They must also monitor the ongoing process carefully to detect any negative effect.

Their next task is to consider their specific research environment, e.g. the availability of others to help make observations and so reduce bias, the ‘paper, pen, tape recorder, and hall time’ kind of resources, the amount of time that will be available, whether the children have recently encountered change and how they reacted to it, the social factors inside and even outside school, in other words all the contextual factors which could impinge on the children’s participation and thus influence the results.

The next part of the definition claims that the researchers must ‘plan, implement then evaluate their action’. The plan is designed to answer a clear, concise, unambiguous and genuine research question. Once this has been formulated, and this takes some time because it has to be suitable, not just for the research topic in the abstract, but for the topic in the context where the research will be carried out, the teachers themselves can design and carry out a series of actions i.e. an action plan, which will produce evidence, i.e. research data, to answer it.

How will the Data be Gathered?

The action plan provides the opportunities to gather data about certain categories of response – as opposed to everything which happened. This is the evidence which will answer the research question. To do this effectively, different data gathering methods must be planned ahead of the first action and ideally administered by different people, so that the findings may be compared and ‘true’ results recorded. This is called triangulation. Each record, whether it be taking field notes or completing observation schedules or tape recording oral contributions to a discussion, should be unobtrusive, otherwise the children will change how they behave and distort the data. Furthermore, the aim is to gather objective evidence of things which consistently occur, rather than ‘one-off atypical blips’ which could distort the findings. This means that data has to be gathered on several occasions and possibly in different venues to try to obtain a ‘usual’ picture of events.

Collecting objective evidence is not easy, and one reason is that the researchers know their subjects so well. This is at once a strength and a weakness of the action research method. There is no doubt that teachers, knowing their own practice and their pupils intimately, can formulate the most useful and relevant research questions for their particular context. In addition, they are experienced observers of children of that particular age group and understand the nuances and foibles that occur. These are clearly strengths. But unless care is taken, they could be weaknesses too. This is because such familiarity can prevent teachers seeing ‘clearly’, as possibly a stranger would, for teachers in their own classroom are likely to have preconceived assumptions about their children and how they might cope with any innovation, and may have difficulty seeing beyond these! This is a possible source of bias and can distort the research findings.

Therefore another very important principle is that researchers take every possible step to reduce bias and make their findings as objective as possible. If this happens, the research should be as ‘reliable’ as it can be. This means that if someone else was to carry out the same procedures, then the results would be the same. If anyone thinks this is easy, try asking two people to observe the same part of a lesson and at the end to compare their findings. I guarantee you will be surprised! This kind of mini-activity brings home the pitfalls of teacher research and helps us understand why this method can be justly criticised if the researchers cannot show that they have adhered strictly to the principles which have been established to give the investigation credibility.

If all of this seems too complex, it can be a comfort to realise that carrying out research need not be an individual effort. Groups of teachers can agree a topic and enrich the investigation by having several readers, planners and discussants. Several banks of experience can really illuminate the starting point, e.g. in finding how different teachers cope with unruly behaviour, in collating views on how different teaching methods affect children’s learning, or how visual aids have been used to reinforce problem-solving strategies. Certainly there will be more eyes to reduce bias, perhaps through taking quite simple measures like changing groups at the observation and data collection times.

A cooperative arrangement like this will mean that more children can be studied and so more data will be available for analysis. In addition, the findings might point to explanations of how and why a particular innovation ‘worked’ in one situation and not in another, thus producing a richer report and possibly helping more teachers understand how the innovation could work for them. This would enlarge the potential generalisation of the research, i.e. the possibility that the findings could be applicable in more ‘other’ situations. This is very important, for small-scale action research in classrooms can be criticised if the findings are so specific that they are no use to anyone else, i.e. if they are not generalisable (Brown 1990). And several researchers investigating the same topic would hopefully be able to make a significant impact on present understandings and this would be very helpful to the profession. But of course they would have to spend a great deal of time together, deliberating the ideas and action plans and engaging in constant evaluation. Not always an easy thing to do!

N.D. Students who wish to engage in collaborative research for an award, need to check the regulations on this in their own institution and if this is agreed, be sure they are clear on the marking procedures.

The research itself is a lengthy process and researchers eat, live and sleep it. It needs a great deal of commitment. This is why teachers have to be sure that their topic is stimulating and ‘enduring’ and has enough substance to be worth all the effort. Furthermore, action research isn’t simply planning a change and carrying it out. All the time, ongoing evaluations cause amendments, perhaps a shift in strategy, or taking more time, or working with more children, or perhaps redefining the research question itself. There are ‘highs and lows’, and often researchers feel that it is all too much. But one of the greatest strengths of action research is being able to choose a relevant, timely topic, and another is the facility to react to the context and the findings as they unfold. This does not imply that topics can just be abandoned without careful consideration; it means that as the investigation develops, and other things become significant, there is room to react to surprises and find out even more interesting things. Then it becomes a great thing to have done. Action research in classrooms then, can be:

- creative;

- contextualised;

- realistic;

- flexible;

- rigorous;

- illuminating.

It is:

- creative, because teachers themselves can choose a topic which is intriguing and challenging as well as being appropriate for the pupils who are involved;

- contextualised, because the entire plan is thought through by teachers in their own setting i.e. people who know the day-to-day planning, the pupils who are to be involved and the classroom organisation which exists. As a result, the action can be meaningful, and be absorbed into the daily routine without disrupting the curriculum;

- realistic, because their intimate knowledge of the context allows teachers to gauge what needs to be done, and what can be done amidst all the other pressures of the classroom day. A small-scale study can give rich findings. Using a sledgehammer to crack a nut is definitely not part of action research;

- flexible, because it can respond to unforeseen circumstances. Very often action research is planned to happen at a certain time each week, but if other contingencies arise, such as pupils being absent or rooms or equipment not being available, then it can be moved. In fact, moving it may be one way of reducing bias. If, for example, the pupils are tired and restless at one particular time of the day, the teachers could attribute their lack of attention to lack of interest in the activity, rather than the tiredness itself. Of course, altering the schedule would depend on other factors, e.g. whether teachers or pupils from other classes or any outside agencies were involved. These considerations aside, a measure of flexibility is generally possible and this can be important in reducing bias for the findings and preventing stress for the researchers;

- rigorous, because if all the results of the research are to stand scrutiny, i.e. to be reliable and valid, then all the stages have to be carried out according to the principles of action research;

- illuminating, because if these principles are adhered to, the researchers can go beyond describing what occurred and explain why things are as they are. Just unlocking one key or discovering one nugget, rather than a gold mine, can be tremendously revealing and exciting and make all the hard work worthwhile.

Another point concerns originality. Postgraduate research students are often puzzled by the requirement for ‘original work’ for an M.Ed, or Ph.D. thesis and are nervous of choosing something that has been researched before. It is very difficult, however, to find a truly ‘original’ topic, but the originality can come from the method, from the different focus which is implicit in the research question, from the context where the action happens, or from the action plan itself as well as from reporting the ‘original’ responses of the group being studied. It need not mean that a pristine, untouched topic has to be conceptualised...