eBook - ePub

Principles of Microeconomics

Peter Curwen, Peter Else

This is a test

Share book

- 402 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Principles of Microeconomics

Peter Curwen, Peter Else

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

`Else and Curwin make an effort to keep the student in touch with recent developments by including such topics as bargaining search, contestable markets and voting behaviour...it will certainly appeal to those who wish to keep economic theory accessible to as wide a range of students as possible.' Times Higher Education Supplement

This clear, concise introduction to intermediate microeconomics is essential reading for students with previous knowledge of economic principles. Geared to the standard year's course in universities and polytechnics, the treatment in this text reinforces the student's understanding of familiar topics and facilitates assimilation of new material.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Principles of Microeconomics an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Principles of Microeconomics by Peter Curwen, Peter Else in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Negocios y empresa & Negocios en general. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

THE BASIC THEMES OF MICROECONOMICS

The scope of microeconomics

Microeconomics is principally concerned with the behavior of individual participants in the economy. Whilst the prefix ‘micro’ suggests a concern with small units, not all these participants – usually referred to as economic agents – are small in any absolute sense, since as well as individuals they include firms, governments, trade unions and many other organizations. They are nevertheless the basic decision-making units of an economic system and, despite their diversity and size, economists believe that their behavior can usefully be analyzed in the context of a common analytical framework. Traditionally, of these economic agents, individuals and firms have been the main focus of attention and that is reflected in this book. But in recent years particularly, the same analytical approach has been increasingly applied to other organizations, and some of the results of that work are also reflected in later chapters.

Microeconomics, however, goes beyond the analysis of the behavior of individual agents in that it is also concerned with the way the decisions of economic agents interact in the determination of the allocation of resources between uses in an economy. In fact there are two aspects to economists’ concern with the allocation of resources. The first is the positive aspect, in which the interest is basically in how resources are allocated under various conditions, although in this book, as in other similar books, the emphasis will be on situations in which resources are mainly allocated through markets, since that is an important common feature of western economies. The second aspect of concern, the normative aspect, stems from the first since, once an understanding of the factors determining the allocation of resources has been obtained, it is a natural consequence to enquire into the circumstances under which such an allocation might be improved. This is the particular concern of welfare economics, which is the subject of chapters 20–22, but particular normative issues are also raised in the preceding chapters.

Choice, rationality and utility

In studying the behavior of economic agents, microeconomics is primarily concerned with the choices they make that have implications for the allocation of resources. It is thus basically concerned with the decisions agents make about how to use the resources at their disposal, particularly the extent to which they seek to use them for consumption, for production, or as a means of acquiring other resources through trade. The key assumption in the analysis of these decisions throughout microeconomics is that, in making choices, individuals behave rationally. That means no more than that, when faced with a number of possible choices, the agent will choose the one that appears to him to have the most preferred outcome. The agent’s choice might seem odd to anyone else. It may even turn out to be a wrong choice from his own point of view, in that with hindsight he may have preferred to choose something else, but that is not the same thing as being irrational. An irrational choice is one in which an individual willingly and deliberately chooses something that in the light of all the information available to him is likely to yield a less preferred outcome to some of the other possibilities on offer. The possibility that people may behave irrationally from time to time, some perhaps more often than others, cannot be ruled out. But looking at the way in which man has applied his mind, over thousands of years, to the analysis of his environment with a view to controlling it and manipulating it to suit his own particular needs and convenience, an assumption that in general economic agents behave rationally does not seem an unreasonable one. However, since the idea of rational choice is so basic in microeconomics, it is desirable to consider a little more formally what it entails before moving on to a closer examination of how it applies to particular economic agents.

First and foremost, it requires individual agents to be capable of assessing a number of different states and ranking them in a definitive order of preference. More specifically, it implies an assumption that an individual agent, when faced with two states A and B, which may be two bundles of goods available for consumption, or alternatively production or trading possibilities, will be able to decide whether A is preferred to B, whether B is preferred to A or whether he is indifferent between them. That is the assumption of comparability.

A second assumption that is usually made is that, when the choice is extended to include one or more additional states, there will be consistency in the ordering of pairs of states, in the sense that if A is preferred to B, and B is preferred to C, then A will also be preferred to C. In more technical terms this means that preferences are transitive, and this is referred to as the assumption of transitivity. In some forms of social organization where decision-making relies on an aggregation of divergent individual preferences, as for example in voting procedures, it turns out that rational decision-making could be inconsistent with transitive preferences, but as far as individuals and more monolithic organizations are concerned it would seem reasonable to expect some degree of consistency. Transitivity will, therefore, be assumed in the following pages unless there are specific reasons to suggest the contrary.

The actual preference ordering that emerges under these conditions will, of course, reflect individual tastes and idiosyncrasies. It will also depend on the nature and functions of the economic agent concerned. But the fact that an agent prefers a particular state to any others he could choose implies that it offers him more of something than any of the alternatives – the opportunity of more pleasure or satisfaction or possibly less dissatisfaction – and that ultimately lies behind the preference ordering. That vague ‘something’ is what economists refer to as utility. Another way of saying that a particular economic agent prefers state A to state B is, therefore, to say that state A yields more utility than B. Similarly, choosing the particular state that is highest of all those on offer in the individual agent’s order of preference can be described as choosing the state offering the highest level of utility. In other words, rational behavior can be identified with an attempt by economic agents to maximize their utility, and hence in subsequent chapters we will be very much concerned with an analysis of utility-maximizing behavior.

What determines utility depends very much on the nature of the agent concerned. The relationship between utility and the variables on which it depends is referred to as a utility function, and one of our tasks in the following chapters will be to consider the nature of the variables in the utility functions of individual consumers, firms and other organizations, and any general properties that can be ascribed to them.

However, one further general assumption that is convenient to make for all agents is that of continuity. Continuity implies that there is a continuous relationship between the amount of utility and the variables on which it depends. Basically this means that, in any situation, changes can be defined yielding infinitesimally small changes in utility. If, for example, utility depends on only one variable, the utility function can be represented by a continuous curve on a graph. One obvious justification for this assumption is that in practice individual agents are typically faced with an infinite number of choices. Think, for example, of the number of ways in which Mr and Mrs Average can spend their weekly earnings, some of which will vary only very marginally from others. Rationality requires all these to be included within the preference function, and therefore necessarily implies something that at least closely approximates to continuity.1 In practice, rationality may in fact be bounded, in that only a restricted range of possibilities may actually be considered when choices are made. This is largely because human beings have a limited capacity to assimilate and process information, but it doesn’t materially affect the continuity assumption. The assumption of continuity has the further advantage that it facilitates the application of mathematical and diagrammatic techniques or analysis. Hence utility functions will be assumed to be continuous unless there appear to be good reasons to suppose otherwise.

It might be felt that there is some contradiction between the idea of a utility function to which specific mathematical properties can be assigned, and our original definition of utility as a vague ‘something’ reflecting relative satisfaction in some rather ill-defined way. It should be recognized at the outset, however, that the use of the utility function concept need not in itself imply that utility can be measured in precise quantitative terms. It is sufficient if different levels of utility can be reflected in an arbitrary index varying in the same direction as utility, which in turn simply requires that the levels of utility experienced in a number of different states can be compared to the extent of identifying whether one gives greater or less utility than the other. In other words, all it requires is that preferences are comparable and transitive.

A relevant distinction here is between cardinal and ordinal measurement. Cardinal measurement is possible when exact units of measurement can be defined, like metres or kilograms or degrees Celsius. Where this can be done, not only can different states be compared in the sense, for example, that it can be established that one object is heavier than another, but it is also possible to measure the difference and compare it with the difference between two other states. With ordinal measurement different states can be ranked in order, but nothing precise can be said about the magnitude of the difference between them. The question of whether and under what conditions it is possible to go beyond ordinal comparisons of utility levels is another issue to be considered more fully in a later chapter, but for the moment it is sufficient for the reader to be aware that the use of the concept of the utility function, and indeed the deduction of a number of important propositions about the behavior of economic agents, requires no more than the ordinal measurement of utility.

Constraints on choice

Whilst rationality is one important element in the analysis of the behavior of economic agents, another is the range of choices actually open to them. The ability of economic agents to maximize their utility tends in practice to be severely constrained by physical and environmental factors that restrict the availability of resources. Economic agents thus are typically faced with a constrained maximization problem, and one of our tasks in the following chapters will be to examine the constraints on the behavior of the particular economic agents to be studied. In almost all cases, however, when man is faced with constraints on his activities, his natural reaction is to seek ways of evading the constraints, or at least of moving them in a way that widens the available choices.

As far as economics is concerned, four particular means of widening choices – production, research and development, trade, and cooperation with others in a variety of social organizations – are of such fundamental importance that their role in this context merits discussion before getting down to the more detailed analysis of the behavior of particular agents.

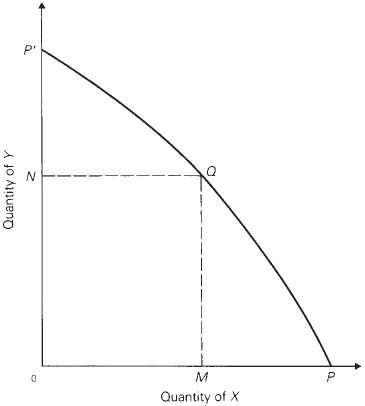

Figure 1.1

Production

The first, and perhaps most fundamental, of these is production. In essence, production can be defined as the process of transforming resources or bundles of resources into something else.

The relationship between the output of any product and the quantities of resources, or inputs, used to produce it is reflected in a second important function, the production function. The properties of this function will be discussed in detail in chapter 9, but, given scarce resources, in any state of technical knowledge there will still be a constraint on what can be produced and, therefore, ultimately on what can be consumed. This constraint is known as the production possibility frontier. In practice it will normally be multidimensional, but where the agent has the opportunity to produce two goods it can be shown on a diagram as a production possibility curve.

Such a curve is shown as PP´ in Figure 1.1 and it can be interpreted as showing the maximum quantity of Y that can be produced with any quantity of X (or vice versa). Hence point Q on the curve indicates that N is the maximum of Y that can be produced with M of X, and that M is the maximum of X that can be produced with N of Y.

Whilst the precise shape and position of the production possibility curve will depend on the production functions for X and Y respectively and the total resources available, a downward-sloping curve can normally be expected since, if the available resources are fully utilized, more X can be produced only if resources are switched from the production of Y. In other words, the production of X has a cost in terms of the production of Y that has to be given up in order to release the resources required to produce X. Thus, at Q in the diagram the cost of the M of X that is produced is the potential P´ N of Y that is forgone.2 At the margin, however, the number of units of Y that have to be given up to gain an extra unit of X in any given situation is reflected in the slope of the curve at the point representing that initial situation.

Alternatively, the slope of the curve can be interpreted as indicating the extra Y obtainable by giving up a unit of X, and this is defined as the marginal rate of transformation of X into Y (MRTXY). However, it is often more useful to measure the cost of the two commodities in terms of some common numeraire such as money, rather than in terms of each other. In that case if, to take a particular example, the marginal rate of transformation of X into Y turns out to be n (i.e. n units of Y are gained if 1 unit of X is given up and the resources are switched to the production of Y) the implication is that in terms of that numeraire good, whatever it happens to be, the cost at the margin of 1 unit of X is the same as the cost of n units of Y, or

MCX = nMCY

where MCX and MCY are the marginal costs of X and Y respectively, and hence

MRTXY = MCX/MCY ( = n).

Since on this definition, with positive marginal costs, MRTXY is the ratio of two positive numbers, it must itself be positive. Mathematically, however, the slope of the production possibility curve is the ratio of the change in Y to the change in X (or Y/X) for small movements along PP´. But since, given the curve’s downward slope, X and Y change in opposite directions along the curve, X and Y have opposite signs in that one is positive and the other negative and their ratio is accordingly negative. In strict mathematical terms, therefore,

slope of PP´ = - MRTXY = - MCX/MCY.

Hence, if MCX and MCY are invariant with respect to changes in output, their ratio (MCX/MCY) is constant, and the production possibility curve is a negatively sloped straight line. If, however, MCX increases relative to MCY as the output of X increases, the curve is concave to the origin, as in the diagram, whilst in the opposite case it is convex.

Research and development

Research and development covers any activity designed to increase man’s knowledge of his environment, and to apply that knowledge to the discovery of improved and more efficient methods of production and to the development of new goods and services. The wide and ever-increasing range of goods and services available for our enjoyment in advanced economies is the obvious result of this kind of activity, which can be characterized as widening choices by pushing the production possibility frontiers of economic agents outwards and increasing their dimensions. In fact, in much of microeconomics where the concern is the behaviour of agents and the resultant allocation of resources at a particular moment of time, the state of technical knowledge can be legitimately taken as given and constant. However, the actual allocation of resources to research and development, involving as it does the assessment of potent...