![]()

1

Behavioural economics and bounded rationality

The discipline of political economy (or ‘economics’, as it has been known since the turn of the twentieth century) has always overlapped with that of psychology. Indeed, being the ‘science which studies human behavior as a relationship between given ends and scarce means which have alternative uses’ (Robbins, 1932: 16), this overlap is unavoidable. Avineri (2012), for example, argues that in his Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759), Adam Smith asserted the importance of psychological insights for understanding individual economic behaviour, including notions such as habits and customs, and also concerns about social wealth, fairness and justice. Then in March 1979, with the publication of the article ‘Prospect theory: an analysis of decision under risk’by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, this overlap between these two disciplines experienced a dramatic turn: it became a field of study in its own right and the discipline of behavioural economics was born, which focuses explicitly on the study of economic decision-making and on issues such as those raised 150 years ago by the founder of modern economics. Only four years later, the first conference dedicated specifically to the new field was held at Princeton University (Frantz, 2004), securing its place in the economics discipline.

Over the past thirty-five years, and particularly in the last decade, behavioural economics has experienced astonishing growth as a separate field of economics. Earl (2005) identifies four indicators of this growth:

- That two Sveriges Riksbank Prizes in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel (Nobel Prizes) have been awarded to academics working in this field (Herbert Simon in 1978 and Daniel Kahneman in 2002); although Frantz (2004) claims that those awarded to George Akerlof and Joseph Stiglitz in 2001 were also for works of behavioural economics.

- The rapid expansion of the literature: Burnham (2013) observes that there now exist in excess of 50,000 papers that cite the works of Kahneman and Tversky (1979) and Tversky and Kahneman (1974), making a comprehensive examination of the field almost impossible.

- The growth in the number of academic societies and journals that are devoted to the field, including the International Association for Research in Economic Psychology, the Society for the Advancement of Socio-Economics and the Society for the Advancement of Behavioural Economics; and the Journal of Economic Psychology, the Journal of Socio-Economics and the Journal of Economic Behavior and Organisation, respectively.

- That numerous economists working in the field have been hired by leading United States universities (and those across the world), along with the media attention that the field has enjoyed, perhaps most notably the New York Times article on 11 February 2001 by Uchitelle.

Further evidence of this growth lies in the fact that, because of its appeal to pre-university students (the ‘Ariely effect’), it is the only new field being included in three of the four largest further-education economics specifications in the United Kingdom, which are being revised for 2015 onwards.

However, the course on which the development of behavioural economics is being steered is curious and possibly concerning. Predating the seminal work by Kahneman and Tversky by two decades, Herbert Simon developed the concept of ‘bounded rationality’. This asserts that the cognitive abilities of human decision-makers are not always sufficient to find optimal solutions to complex real-life problems, leading decision-makers to find satisfactory, suboptimal outcomes. Simon’s work was a foundational component of the development of behavioural economics as a field in its own right, but despite receiving the Nobel Prize for economics in 1978 for ‘his pioneering research into the decision-making process within economic organizations’ (Nobelprize.org), Simon’s work has of late been, at least partially, overlooked in the behavioural economics literature. For instance, the aforementioned New York Times article by Uchitelle failed to refer to either Simon or his work.

The fields of behavioural economics and bounded rationality, even though they both emerged due to discontent with the descriptive and predictive power of the standard economics model of rational choice, have evolved in different directions, each with its own literature, its own approach and its own proponents. As will be further elucidated below, the former is concerned with the integration of methodology from psychology into economics analysis, whereas the latter largely analyses the implications of suboptimal decision-making through the mathematically sophisticated methodology of mainstream economics. The purpose of this research monograph is to examine the nature, the consequences and the advantages and the disadvantages of these different evolutionary paths, and to identify avenues of research in economics that would benefit from a re-fusion of these two fields. In particular, the intention is for this monograph to address four issues:

- The nature of the different evolutionary paths of the literatures of behavioural economics and bounded rationality. For example, the intention is to answer questions such as: With what issues are they each concerned? What approaches to their studies do they each employ? Who are the primary audiences of each? And what are the areas of commonality and difference between them, in terms of their focus, methodologies and applications?

- The consequences of this evolutionary divide. In terms of the areas of focus that are common across these two fields, to what extent do they lead to compatible conclusions? Do the methodologies employed in each literature naturally lead to different outcomes and, if they do, what is the significance of this?

- The advantages and disadvantages for economics as a whole of these two fields evolving in the different directions they have taken. To what extent is the specialisation that has occurred positive for, and to what degree is it impeding the development of, the wider subject?

- The lessons that can be taken from an assessment of all of the above. Should this increasing divergence be promoted or counteracted, and are there areas of research for which a re-fusion of these literatures and approaches would be beneficial?

Behavioural economics

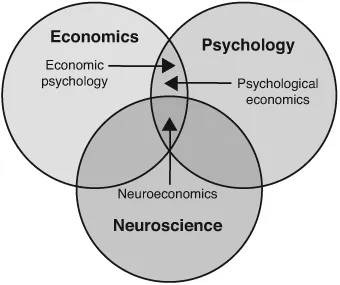

It is not at all clear at first glance what is meant by ‘behavioural economics’. As noted above, it certainly occupies space within the area of overlap between the disciplines of economics and psychology. However, that area is vast and consists of a literature composed of a whole array of different methodological approaches, applied to an even larger array of questions and concerns. This is illustrated in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 The nature of behavioural economics and bounded rationality

Earl (2005) suggests that there are two general approaches within this area of overlap between economics and psychology, an assertion that is supported by Fetchenhauer et al. (2012). The first is that of studies that seek to apply economic methodology and reasoning to issues that have traditionally been considered to be within the domain of psychology. They can be seen to be extending the realm of economics and can be labelled as studies of economic psychology. The quintessential example of such work is that of Becker, who employed the framework of neoclassical economics to analyse issues that were not traditionally economic in nature, including drug addiction, the family, and marriage and divorce. The second is that of studies that seek to apply methods and reasoning from psychology to issues that have traditionally been viewed as being the subject matter of economics. These can be seen to be extending the realm of psychology and so can be labelled as studies in psychological economics. In addition to these, there also exists the influence of neuroeconomics, which consists of studies that seek to apply the techniques of neuroscience to the analysis of economic issues: the ‘brain studies’, which ‘monitor brain activity during decision making’ (Rubinstein, 2007: 1244) (for a survey of this field see Camerer, 2007, which discusses the implications of neuroeconomics for economics, particularly in terms of the strengths that it has identified of the standard model of rational choice and the approaches of behavioural economics).

Following the judgement by Earl (2005), behavioural economics is taken to refer to the field of psychological economics: a field that ‘seeks to use inputs from psychology to obtain an enhanced understanding of, and/or an improved ability to predict, behavior in respect of areas that have normally been viewed as the preserve of economics’ (Earl, 2005: 911).

Bounded rationality

Simon (1955: 99) argues that the standard model of rational choice assumes that a decision-maker possesses:

knowledge of the relevant aspects of his environment which, if not absolutely complete, is at least impressively clear and voluminous. He is assumed also to have a well-organized and stable system of preferences, and a skill in computation that enables him to calculate, for the alternative courses of action that are available to him, which of these will permit him to reach the highest attainable point on his preference scale.

Doubting the realism of this assumption of global, or objective, rationality, Simon repeatedly asserts that, ‘as soon as we turn from very broad macroeconomic problems and wish to examine in some detail the behavior of the individual actors, difficulties begin to arise on all sides’ (1957: 197). As an alternative, Simon proposes the principle of bounded rationality, which models decision-makers as being unable, most of the time, to identify, assimilate and process information in an optimising manner: ‘the capacity of the human mind for formulating and solving complex problems is very small compared with the size of the problems whose solution is required for objectively rational behavior in the real world – or even for a reasonable approximation to such objective rationality’ (1957: 198). With cognitive abilities not equal to the complexity of the decisions they have to make, decision-makers cannot optimise objective functions and so, by necessity, employ alternative cognitive strategies to make decisions. Indeed, decision-makers search for satisfactory outcomes by applying ‘rules of thumb, or heuristics, to determine what paths should be traced and what ones can be ignored’ and that the ‘search halts when a satisfactory solution has been found, almost always long before all alternatives have been examined’ (Simon et al., 1992: 4). The first part of this, that decision-makers do not always possess cognitive capacities equal to the complexity of decisions they face (what Heiner, 1983, has termed the ‘C-D gap’) and so are unable to make decisions optimally, is the principle of bounded rationality. The second aspect (that they consequently search for a satisfactory outcome when making decisions) is the concept of satisficing.

Working in collaboration with Charles Holt and Franco Modigliani on the project ‘Planning and Control of Industrial Operations’ at the Graduate School of Industrial Administration of the Carnegie Institute of Technology, Herbert Simon and John Muth arrived at diametrically opposite views about decision-making within economic organisations: bounded rationality and rational expectations, respectively. While the former asserts that decision-makers do not always possess the capacity to make decisions optimally, the latter asserts that ‘economists and the agents they are modeling should be placed on an equal footing: the agent in the model should be able to forecast and profit-maximize and utility-maximize as well as the economist – or should we say econometrician – who constructed the model’ (Sargent, 1993: 21). The former leads to the conclusion that decision-makers inevitably settle for outcomes that are ‘just good enough’, whereas the latter leads to the conclusion that they are able to construct forecasts about economic data that contain no systematic error whatsoever.

The economics profession has favoured the rational expectations view and has, at various times and in various forms, sought to sideline Simon’s alternative of bounded rationality. Perhaps inevitably given it was the birthplace of both bounded rationality and rational expectations, Simon arguably found his greatest critics within his own economics department at the Carnegie Institute of Technology: opposition that at least partially contributed to his decision to relocate to the Psychology Department (see Sent, 1997). Despite having received the Nobel Prize in 1978, Simon later lamented, ‘my economist friends have long since given up on me, consigning me to psychology or some other distant wasteland’ (1991: 385). It appears that this is continuing, with bounded rationality being sidelined or consigned to footnotes in the burgeoning behavioural economics literature.

Returning to the categorisation of Earl (2005), then, bounded rationality in the sense that Herbert Simon intended – based on suboptimal decision-making and satisficing – can be seen to also be within the field of psychological economics (indeed, psychologists often claim Simon as one of their own). However, bounded rationality is often modelled within the literature as the addition of further constraints on a utility-maximisation process. It is not at all clear how this should be categorised according to the framework of Earl (2005). On one hand, it attempts to take account of psychological constraints in economic decision-making and so in that sense can be viewed as an extension of psychological principles into the economics domain, placing it securely within the field of psychological economics along with behavioural economics. However, on the other hand, by maintaining the neoclassical assumption of utility-maximising agents, it extends economic methodology into decision-making situations that are traditionally the domain of psychologists, locating it within the economic psychology field.

The distinction

Behavioural economics, then, is the study of all aspects of economic decision-making. This includes the nature of people’s preferences, both personal and pro-social; the actual cognitive processes that decision-makers employ when making their decisions; and the ways in which such decision-making is influenced by wider factors and so can be manipulated (both in positive and negative ways for decision-makers). Bounded rationality, by contrast, is much more narrowly focused on the analysis of decision-making when the decision-maker does not possess the cognit...