eBook - ePub

Urban Nature Conservation

Landscape Management in the Urban Countryside

Stephen Forbes, Tony Kendle

This is a test

Share book

- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Urban Nature Conservation

Landscape Management in the Urban Countryside

Stephen Forbes, Tony Kendle

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Urban nature conservation is a field that has grown rapidly in importance over the past 20 years and will continue to do so in the coming years as landscape ecology and greenspace planning become established disciplines. A widespread concern and interest in the wild plants and animal life found in urban areas now influences the policies and practices of land management organizations. This book provides a comprehensive overview of the subject. It will assist professionals in formulating strategic management policies that integrate urban nature conservation into the wider context of landscape management and urban planning.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Urban Nature Conservation an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Urban Nature Conservation by Stephen Forbes, Tony Kendle in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Aménagement urbain et paysager. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Urban Estate and the ‘Urban Countryside’

Firm, quantified, data about the urban countryside do not always come readily to hand. We know surprisingly little about the open spaces that we live among. Even local governments, charged with responsibility for management of much of the land, have until very recently been able to get by with an amazingly vague picture of the land they look after.

Certain changes have occurred in recent years in the UK that will lead to better information supply, most notably the development of land registers, local authority environmental strategies and the requirement for Compulsory Competitive Tendering in local authority departments. Obviously work can not be passed to contractors without some documentation of the nature, objectives and size of the urban estate that is to be managed. However even this data-gathering process will leave us with a very incomplete picture for several reasons.

- Much of the land which is essential for urban wildlife survival lies in private hands (although this is not always beyond the scope of local authority influence through designations such as Tree Preservation Orders).

- It is a characteristic of much of the ‘wild’ landscape of towns and cities that it has developed on land which is neglected and overlooked.

- There are areas where the ownership may not be clear (local authorities often own land that their staff are not aware of), and in many cases the land may be temporarily unused but may be classified by the planning and development control system as something very different to open space.

It has been found that the actual areas of greenspace in urban areas can often be nearly double that of previous official estimates when such sites are taken into account. It can even be a matter of debate whether urban nature is only found on ‘green sites’ since ‘in time all urban plots are capable of supporting natural assemblages, even derelict buildings and car-parks (Harrison et al., 1996).

Not surprisingly, different urban areas show different patterns when surveys are attempted. In a land-use survey for Leicester formal grass counted for about 20%, agriculture, semi-natural land and other miscellaneous accounted for just over 15% and residential and commercial areas accounted for 65%. In the Tyneside/Newcastle conurbation formal grass accounted for less than 10% of the land whereas agriculture and other land uses accounted for nearly 40% and the residential/commercial component was only about 50% (Carr and Lane, 1993). These figures seem to completely overlook gardens as a separate land use. Brussels has about 50% built surface, with 20% open space, 20% private gardens and 10% sports, nature reserves, agriculture and other land uses (Gryseels, 1995).

In the heart of the City of London open spaces make up approximately 7.5% of the urban landscape. Of this nearly half the area is regarded as ‘green’, but of this green space over a third is closed to public access (Plummer and Shewan, 1992). This distribution of spaces is however influenced by the local economy and land use. The West End, has less than a quarter the number of open spaces and a much lower percentage of green spaces; Tower Hamlets has fewer open spaces but the shortfall is mainly because of limited ‘hard spaces’ and the proportion of green is much higher. Vacant land is effectively non-existent in the City reflecting the strength of investment, but such open areas are quite prevalent in the Tower Hamlets area.

The quality of the green space also varies. There is frequently a correlation between site size and vegetation diversity, but this is also affected by the regional economy, for example most spaces in the City of London are highly formal and seen as extensions of the local architecture.

As well as difficulties in comparing because of the different survey criteria and methodology, the figures often depend on arbitrary city or town boundaries which may incorporate more or less greenspace and countryside. Vegetation cover in Berlin ranges from 32% in the built-up areas of the city through to 95% in the outer suburbs (Sukopp et al., 1979).

Depending on the location within the urban framework there can be huge variation in site size. Heavily developed areas and particularly the more historic areas are frequently characterized by very small sites. In the UK the influence of post war planning has often been to preserve larger tracts of land for recreation or amenity, although these tracts are frequently not managed in a way that supports much wildlife. They form the ‘featureless green deserts’ that are widely criticized (Elliott, 1988).

Obtaining figures for urban wasteland is in many ways even more difficult. UK Government statistics on officially abandoned or derelict land can be obtained. (Derelict land in the UK is identified as ‘land so damaged by industrial or other development that it is incapable of beneficial use without treatment’, but excludes sites where the existing developers have planning commitments for restoration.) However it is less easy to identify vacant sites which are technically still in ownership and regarded as ‘operating’ or awaiting development, even though in practice these sites may be effectively devoid of use for decades. It certainly is known that these areas can be substantial. In the town of St Helens in 1989 it was estimated that more than a quarter of the land to the south and east was either derelict or unmanaged (Handley, 1996).

A survey by the UK government of urban areas with populations over 10 000 people suggested that out of a total in England of approximately 940 000 ha, some 50 000 ha could be regarded as derelict or vacant (DOE, 1992) although some non-government agencies would still regard this as an underestimate. However it is also important to recognize the difficulty of value judgements when deciding whether such sites are truly harmful or ‘incapable of beneficial use’. Vacant land can be seen as blighting and corrupting, reducing local environmental quality, reducing economic health and inciting vandalism, all of which leads to a downward spiral of urban quality. However the UK survey mentioned above included an estimate of some 28 000 ha of land which has remained vacant and has never previously been developed. Almost certainly much of this would meet Mabey’s (1973) definition of the unofficial countryside. Many such sites are regularly used and usage levels can be increased to match that of urban parks with the addition of paths and some attention to safety (Handley, 1996).

Despite the complexity of data analysis we are able to recognize that the urban countryside is remarkably diverse and surprisingly capacious. A somewhat easier task is to begin to categorize the main types of urban land that may be of particular interest to conservationists.

Origins of Urban Open Space

There are several locations which are often particularly important components of the urban nature matrix, and these are discussed in more detail below. Their origins are diverse but two main classifications can immediately be identified which will have a huge implication for the existence and allocation of resources for management.

Some are open spaces maintained or created as a deliberate land-use decision. This may include parks, recreation grounds and private gardens as well as sometimes quite substantial areas of landscape associated with large organizations or public buildings such as schools, hospitals and industrial parks. It also includes the non-specific open space, the land that acts as a filler or buffer in housing estates and alongside roads, railways and other transport corridors. Some sites have patches of land that are very diverse and have complex histories such as canals and riversides. It can include encapsulated countryside sites, such as commons, which have become absorbed and maintained as parks.

Despite their historic protection these sites can still be under threat. The privatization of public utilities and the rationalization of health authority and education properties are all likely to lead to the ‘disposal’ of unwanted land. Even parks authorities have been under pressure over recent decades to sell land for development to compensate for falling budgets. None of these bodies has a formal duty to maintain an estate for public or wildlife benefit and the changes in their structure may lead to a dramatic decrease in the proportion of open land in many urban areas.

Some sites have been protected by accident as land that has somehow fallen outside of the development and planning cycle. This could include zones of derelict land, either reclaimed or spontaneously colonized by vegetation, and land which is temporary vacant awaiting development but has in some way survived and become accessible to the public. Sometimes this land becomes formally recognized as a recreation resource. In the UK the Gunnersbury triangle is probably the best example. This is an area of land that was isolated by railway tracks and became gradually colonized by pioneer woodland and other habitats. After a planning battle over a proposed development the land has been retained as a nature reserve for use by the local people.

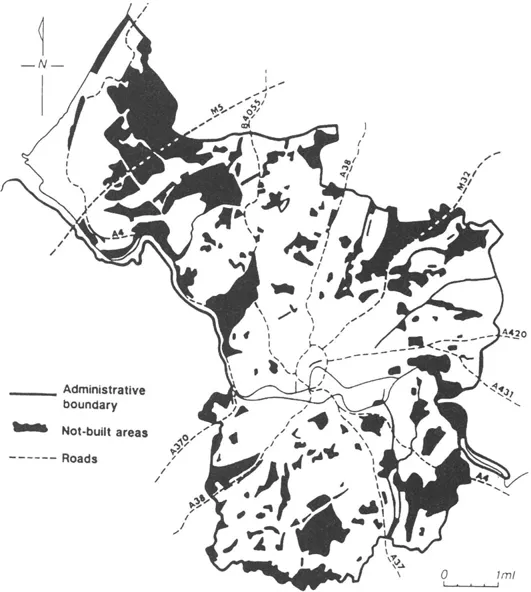

This neglected land may also include areas of relict countryside that have been incorporated, through an accident of geography or history, into the urban fabric but is too difficult for building (Figure 1.1). It may survive because of steep slopes, difficult topography, poor drainage or for administrative reasons such as complex, unclear or communal land ownership. Many of these areas have no official status.

Figure 1.1. Areas within the city of Bristol which have not been built up (Bland and Taylor, 1991).

Obviously these two broad categories of ‘unplanned land’ may differ significantly in that the former is likely to have a preponderance of young, skeletal habitats while the latter can, in some instances, include some very ancient ecosystems. It is the latter that is likely to be seen as the most important in traditional conservation terms although there are exceptions as we shall see later.

One key characteristic that links these latter sites is that their day-to-day survival in urban areas has been dependent on neglect rather than on deliberate policies of land use. Indeed much of this land would be officially categorized as ‘waste’ or functionless. This does mean that the sustained existence of these sites can be fragile and threats may easily arise. For example in the UK local authorities are being encouraged to promote development activity on ‘forgotten sites’ that they own. It is not surprising therefore that, from time to time, local communities become involved in battles to protect these areas, and that many benefit from formal recognition as areas of local open space.

Even those sites which have been protected by their physical nature may now be threatened by increased development pressure supported by improvements in technology such as ‘raft’ foundation construction techniques for building on poorly drained sites.

Urban Sites of Particular Importance

Churchyards

Churchyards and cemeteries are recognized as being among the most important urban nature reserves (Gilbert, 1989). Many of the oldest represent a direct link to historic countryside. Some areas of turf have never been disturbed or fertilized and therefore may contain important relict communities of wildflowers. Many such sites also contain very old trees and the stone features such as gravestones can provide an important habitat for lichens and mosses. Cemeteries, as opposed to churchyards, have frequently undergone dramatic changes in habitat status since once they have become full, revenue sources to pay for management rapidly declines. Many of the oldest have therefore become overgrown and dominated by invading scrub and trees, together with those ornamental species that were able to maintain a competitive place in the plant community.

As well as their natural history interest such areas also have high importance in terms of their social impact. All good landscapes speak to our feelings, and cemeteries must be potentially among the most emotionally charged places we ever encounter. People’s feelings when faced by death are inevitably complex, and the challenges of producing a landscape that encompasses and responds to these feelings should not be underestimated. Wild landscapes seem to be relevant in at least part of these areas because they can create a sense that ‘life goes on' or that nature finds new life in death.

This is of course the same sentiment that lay behind the use of evergreens in churchyards for centuries and reached a peak in Victorian times. However today we have more complex associations with many of the evergreens that the Victorians loved and we cannot read the same messages in the landscape. Conifers are ‘aliens’ associated with afforestation and with dingy grime-covered shrubberies lining urban streets. Today we need new landscapes that evoke the same feelings for our own generations and objectively natural landscapes seem particularly appropriate; if carefully designed, long grass and wildlife can present a powerful message of the natural cycle and of renewal. Evergreens will play a part, but they should be used as a small element of a more natural habitat, not as the dominant focus.

It seems particularly ironic that new cemetery designs are among the most uncomfortable, sterile and mawkish mish-mashes of structureless and often over-maintained planting imaginable, embodying the worst of municipal omamentalism. Angular hybrid tea roses sit awkwardly in beds carved out of close mown grass in a setting that seems devoid of an appreciation of any spiritual and cultural dimension. The justification given for such styles is usually that people want and appreciate these plants, and that wild landscapes are equated with a lack of care. Leaving grass uncut is interpreted as an insult or at least a shocking dereliction of duty on behalf of the management authority. (Although it needs to be recognized that there is a growing interest in ‘ecoburials’ where people choose to be buried in natural surroundings, so stylistic preferences for cemeteries may change in the future.)

In a way, therefore, cemeteries and churchyards embody a philosophical, almost spiritual, debate that lies at the heart of the urban conservation movement. For many people, allowing nature more freedom within the cemetery is corrupting and somehow equates with a lack of human care, or worse a complete moral abandonment. The value of wildlife as a positive factor in the landscape, and the need for and value of human involvement in the management of nature is poorly recognized.

Nevertheless this cannot be tackled by attempts to ‘ban’ exotic plants or force people to live in more natural surroundings. At present anyone who does favour more natural settings in cemeteries will find their choices reduced by a vociferous lobby, and there is nothing to be gained by replacing this with another extreme stand. The need is to encourage more choice through promoting more positive associations of nature in urban areas, and more examples of good naturalistic designs but also to recognize that these will always need to integrate with more formal and ornamental areas.

Gardens and Private Open Space

Outside of the urban heartlands of shopping precincts, offices and the most intensely developed workers terraces, where hard surfacing and concrete are dominant, towns and cities retain a remarkably large percentage of green, and this remains the case even when looking at housing estates and urban layouts from many different social periods. However, the pattern and content of the land often changes dramatically as does the division between private and public land. As a consequence the importance of the land to urban conservation and the potential for wildlife support also varies.

The patterns of land and land use in urban areas is inevitably closely influenced by social and historical factors. Most of the towns in Europe have grown organically over centuries. There are many different layers of urban development - a medieval core in some cases but nearly always areas of Victorian and Edwardian development as well as phases of planned urban expansion carried out in almost every decade of the twentieth century. It is a fairly simple task to date zones of the urban fabric by looking at the architectural style of the buildings and road patterns. What may be less obvious is that the nature of the landscape also follows certain predictable trends and can also be dated from its appearance and content.

Early urban cores are often fairly deficient in open space, unless there has been significant redevelopment since (or because of) the last world war. Although the original developments may have incorporated more open land, centuries of infilling during times of population pressure have almost entirely eroded this resource. Notable exceptions are often associated with powerful landowners of the past, such as the church or colleges.

Victorian residential developments are characterized by relatively large gardens for certain privileged classes whereas the majority of workers’ housing had little associated ground. In compensation the Victorians invested in allotments and large urban parks; the former to be used to provide a healthy diet and the latter to contribute to health and social wellbeing by providing resources for fresh air, recreation and also beauty to refresh the spirit and to civilize the working classes. The Victorians therefore anticipated many of the ideas of the multiple benefits from urban greenspace that we still hold dear today. In many ways it was only their limited grasp of issues such as the nature of pollution and plant ecology that limited the sophistication of their projects. It was also an age where there were relatively few controls over development. Social reformers could have an impact in very specific instances, but were unable to dictate that what we would now call ‘environmental issues’ should be given consideration in wider development.

The inter-war years were characterized by the increasing influence of planning in town development. Housing areas were influenced by the ‘garden city’ philosophers who wished to place more emphasis on gardens for all dwellings and also on the provision of more greenspace around and between buildings. Grass...