![]()

Introduction

Clayton Clemens and Thomas Saalfeld

The German general election of 18 September 2005 was remarkable for a number of reasons. Firstly, it was unusual in terms of its timing and the manner it was brought about: The Bundestag elected in 2002 was dissolved more than one year before the end of its regular ‘constitutional inter-election period’,1 triggered through Federal Chancellor Gerhard Schröder’s ‘engineered’ loss of a vote of confidence in the Bundestag. Whilst strategic ‘election timing’ is not uncommon in other parliamentary systems of government2 and constitutes an important agenda-setting power3 in the armoury of many heads of governments in such systems,4 it has been a relatively rare occurrence in post-war Germany.5 With its strong emphasis on government stability, the German Basic Law makes early dissolutions of the Bundestag relatively difficult. Although such dissolutions are not ruled out completely (as, for example, in the Norwegian constitution), the German Federal chancellor and the Bundestag majority are heavily constrained in this respect. The Basic Law does not invest the Federal chancellor with the power to ask the head of state for an early dissolution, as long as he or she enjoys the support of a parliamentary majority. More importantly, perhaps, it does not grant the Bundestag a right to dissolve itself by a (qualified) majority vote. In practice, therefore, Article 68 of the Basic Law has been used to ‘engineer’ early dissolutions in 1972, 1983 as well as in 2005:6

If a motion of the Federal Chancellor for a vote of confidence is not supported by the majority of the Members of the Bundestag, the Federal President, upon the proposal of the Federal Chancellor, may dissolve the Bundestag within twenty-one days. The right of dissolution shall lapse as soon as the Bundestag elects another Federal Chancellor by the vote of a majority of its members.7

Chancellor Schröder used the vote-of-confidence procedure to trigger an early election after the governing parties– Social Democrats (SPD) and Greens – had suffered a catastrophic defeat in the regional elections of North Rhine-Westphalia on 22 May 2005. As a result of that election, the SPD-Green coalition in Düsseldorf had lost its majority in the state diet (Landtag) and was replaced by a coalition of Christian Democrats (CDU) and Liberals (FDP). This defeat constituted a ‘political earthquake’. North Rhine-Westphalia, the most populous state in the Federal Republic, had been governed by the Social Democrats since 1966. In many ways it had been seen as the party’s social and political ‘heartland’. Disaffected by Chancellor Schröder’s contentious reforms of the labour market (especially the so-called ‘Hartz Reforms’) and other legislation to modernise the German welfare state (labelled by the government as the ‘Agenda 2010’),8 trade unionists and left-wing Social Democrats had formed the breakaway ‘Electoral Alternative Employment and Social Justice’ (Wahlalternative Arbeit und Soziale Gerechtigkeit, WASG), which had challenged the SPD in the state elections of North Rhine-Westphalia (achieving 2.2 per cent of the vote). More importantly, however, the WASG swiftly moved to join forces with the – mostly East German – Party of Democratic Socialism (PDS), thus threatening to create a well-organised and well resourced national party to the left of the SPD.9 Following the shock of the state election in North Rhine-Westphalia, Schröder and SPD leader Franz Müntefering therefore decided to seek an early election at the national level, arguing that the government needed a clear mandate to continue its reform agenda, especially in the face of Christian Democratic majority control of the upper house of the legislature, the Bundesrat. Schröder tabled a confidence motion in the Bundestag on 1 July 2005. A number of SPD and Green Members of the Bundestag (loyal to Schröder) abstained, which led to the (intended) defeat of the government. Schröder could then propose an early dissolution of the Bundestag to the Federal President, who accepted the chancellor’s request. The President’s decision of 21 July was challenged in the Federal Constitutional Court by two Members of the Bundestag (Hoffmann and Schulz). Yet, the Court upheld the dissolution in its decision of 25 August, and an election could be held on 18 September.10

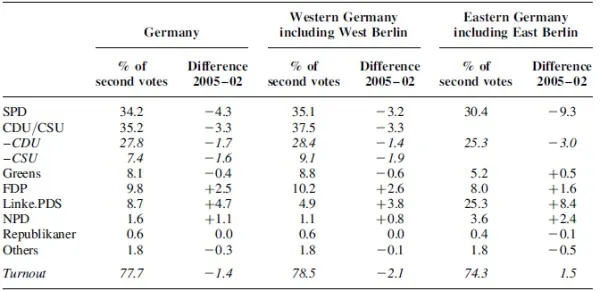

The second distinctive feature of the 2005 election was its result: Compared to the predictions of the main polling institutes throughout the summer of 2005, the outcome was surprisingly close and saw losses not only for the SPD (as expected) but also for the CDU/CSU (see Table 1). At the beginning of the – relatively short – campaign, the pundits (and parties) had expected a clear victory of the Christian Democrats (CDU/CSU) in their alliance with the liberal FDP.11 After all, the Social Democrats had suffered a series of defeats in regional elections (Lower Saxony, Hesse and Bavaria in 2003, Hamburg and Thuringia in 2004, Schleswig-Holstein in 2005) and in the elections to the European Parliament in 2004. However, the elections of 2003 and 2004 did not signal a uniform and consistent swing in favour of the CDU/CSU: The Christian Democrats’ successes in 2003 (Lower Saxony, Hesse, Bavaria) and 2004 (Hamburg, Saarland) were partly offset by (in some cases) substantial losses in Bremen, Thuringia, Saxony, Brandenburg as well as in the European Parliament election. In the immediate run-up to the Bundestag election of September 2005, however, it was the SPD – internally divided over Schröder’s reform programme – that paradoxically appeared to be the more cohesive party. The Christian Democrats seemed far more divided as a party, especially after CDU leader and candidate for the chancellorship, Angela Merkel, had appointed the controversial law professor Paul Kirchhof to be the CDU/CSU spokesman for economic affairs. The SPD leadership managed to polarise the election campaign by portraying the CDU/CSU and FDP as parties intent on ruthlessly dismantling the German welfare state.12 In addition, Chancellor Schröder maintained a lead over his challenger Angela Merkel as the more popular leader.13

Table 1

Distribution of Second Votes in the Bundestag Election of 18 September 2005

Source: Forschungsgruppe Wahlen, Bundestagswahl: Eine Analyse der Wahl vom 18 September 2005 (Mannheim: Forschungsgruppe Wahlen e.V., 2005), pp.86, 88 and 90.

With 77.7 per cent, turnout on election day was only marginally lower than in 2002. The SPD obtained 34.2 per cent of the ‘second’ votes for the party lists14 and lost more than four per cent compared to the election of 2002. Yet the party fared much better than expected (especially in relation to the CDU/CSU). Clearly, Schröder’s surprise move (shifting the focus from the SPD’s problems to the technicalities of the early dissolution) had helped to cut the party’s losses. The CDU/CSU, by contrast, performed significantly below the expectations most observers had at the time the election was called. With 35.2 per cent of the votes, the two Christian Democratic parties lost more than three per cent, if their result is compared to the outcome of the 2002 election. In other words, both major parties were losers of the 2005 election, both faced one of the worst results in their post-war histories. Between them, they were chosen by less than 70 per cent of the voters. The smaller parties fared somewhat better in terms of gains and losses. With approximately 8.1 per cent of the second votes, the Green party managed to protect itself from the SPD/Green (2002–2005) coalition’s crisis and to defend its 2002 share of the votes to a large extent. Even the much-publicised Ukrainian ‘visa scandal’ and the role of foreign secretary and Green leader Joschka Fischer in this affair did not significantly harm the party. The main winners of the election were the FDP, which increased its share of the vote by 2.5 per cent to nearly one-tenth of the votes, and the newly formed alliance of PDS and WASG (see above): If we take the PDS result of 2002 as a baseline for comparison, the Linke.PDS (as they now called themselves) increased their vote by nearly five per cent and were returned to the Bundestag with 8.7 per cent of the votes.

Despite these changes in the electoral ‘landscape’, there were elements of continuity. As Eckhard Jesse pointed out, the election of 2005 resulted in a continuation of the small but significant advantage enjoyed by the centre-left and left in German politics at the national level. The aggregate share of the second votes gained by the SPD, the Greens and the Linke.PDS was 51.0 per cent in 2005, compared to 51.1 per cent in 2002 and 52.7 per cent in 1998. The aggregate share of the votes cast for the centre-right parties CDU/CSU and FDP amounted to 45.0 per cent of the votes in 2005 (compared to 45.9 per cent in 2002 and 41.3 per cent in 1998). Nevertheless, as Jesse points out, this slight left-wing majority is generally a ‘negative’ one: SPD, Greens and PDS are united in their opposition to a cabinet of CDU/CSU and FDP, but there is insufficient common ground between them to form a government.15 Nevertheless, as Charles Lees argues in his contribution to this volume, this overall constellation has given the SPD control of the Bundestag’s median legislator since 1998. The party has therefore been in a strong position in coalition bargaining (see also the contributions of König and Richter to this volume).16

Table 1 demonstrates that the differences between the voters’ choices in Eastern and Western Germany are still considerable. The West German party system consists of two major (CDU/CSU and SPD) and three minor parties (FDP, Greens and Linke.PDS). In Eastern Germany, Die Linke.PDS is a major party whose electoral support is as strong as the CDU’s. The CDU/CSU is the strongest party in the West. Despite its catastrophic losses, the SPD defended its position as the strongest party in the East of Germany. Although the extreme right-wing National Democrats (NPD) made some inroads in 2005, especially in the East, they remained a marginal party in both parts of the country.

The third interesting result of the 2005 German election was its impact on government formation. Table 2 demonstrates that the voters inflicted a bitter defeat on both major parties (CDU/CSU and SPD) and left them with roughly the same number of seats in the Bundestag (226 and 222, respectively). Consequently, the traditional pattern of forming minimal winning cabinets consisting of one of the two major parties and one of the smaller parties (Greens or FDP) was no longer possible in purely numerical terms. Table 3 shows that the only numerically feasible minimal-winning coalitions were either a ‘Grand Coalition’ of both major parties – which had opposed each other in the election campaign – or a three-party coalition consisting of one major and two minor parties. The last time the latter constellation had occurred was the 1957–61 Bundestag. In other words, government formation had become far more complex than at any time since 1961. This complexity was reduced somewhat by the fact that Die Linke.PDS was ideologically too far removed from the CDU/CSU to make a coalition of these two parties politically feasible. Similarly, the fact that the new left-wing party constituted a merger between the PDS and a breakaway faction of the Social Democrats that was co-led by the SPD’s former chairman Oskar Lafontaine made it ‘non-coalitionable’ for the SPD. Since the FDP had expressly ruled out a coalition with the SPD before the election, only two coalitions remained numerically and politically feasible: a Grand Coalition of the two major parties or a co...