eBook - ePub

The Routledge Historical Atlas of the American South

Andrew Frank

This is a test

Share book

- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Routledge Historical Atlas of the American South

Andrew Frank

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book illuminates singular aspects of Southern society and culture and provides justification for thinking about the South as a region unto itself. It also shows that the South in fact consists of many shifting social and cultural sub-regions.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is The Routledge Historical Atlas of the American South an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access The Routledge Historical Atlas of the American South by Andrew Frank in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Economic History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

PART I: THE NASCENT SOUTH

The roots of the American South were planted long before the Confederacy was formed or cotton plantations littered the region. Indeed, a Southern culture existed before the arrival of European settlers in the seventeenth century. The Native Americans indigenous to the southeastern corner of North America shared what archeologists have called the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex. Although the native groups in the region spoke different languages and often waged war against each other, they shared religious beliefs, symbols, customs, and costumes. These inhabitants, who were mostly horticulturists, built enormous earthen mounds as burial grounds, temple mounts, and ceremonial centers. They lived largely in small cities and in hierarchical chiefdoms. These chiefdoms—which included the Coosa, Altamaha, Apalachee, Talisi, and Alibamo—contained powerful chiefs, institutions of centralized power, specialized labor forces, intricate systems of tribute, and sophisticated agricultural practices. Even after the introduction of European diseases largely destroyed these peoples, an Indian presence continued to shape the development of the American South

The European settlement of the American South occurred in piecemeal fashion. In 1607, London's Virginia Company began the first successful attempt by the English to colonize. Their settlement, Jamestown, struggled to survive in its early years. Tobacco horticulture and indentured servitude provided an avenue for economic prosperity for the colony, but local Algonquian Indians prevented true stability. After a series of bloody Anglo-Powhatan wars, Virginians finally obtained control of the region in the late seventeenth century. The other Chesapeake colony, Maryland, began with a land grant to George Calvert, who wished to establish a settlement of Roman Catholics. This colony also became quickly wedded to tobacco, and like Virginia, it faced a labor shortage in the early 1660s. By 1670, planters throughout the Chesapeake relied on the labor of African slaves. Further south, English refugees from Barbados settled South Carolina in the 1680s. There, the cultivation of indigo and the deerskin trade brought a modicum of economic stability. Slave laborers eventually harvested a profitable rice crop, and in 1708 South Carolina had the South's first and only black majority. Four years later, the less prosperous North Carolina officially separated from South Carolina. In 1733, James Oglethorpe established Georgia, the last of the English colonies in the southeast. At first this colony appeared quite different from its neighbors, as its Board of Trustees designed it as a moral experiment. The colony initially banned African slavery, forbade the use of rum and other liquors, and severely restricted trade with the Indians. These bans would not last long, as colonists defied them from the outset. The English were not the only Europeans to colonize the American South. French and Spanish settlers occupied most of the Gulf Coast, including Florida and the lower Mississippi Valley. There, the French and Spanish vied for the allegiances and trade of neighboring Native Americans, built garrisons and missions, and otherwise established permanent settlements.

Beneath the diversity of the Southern colonies lie several themes that affiliated them with each other and with the more unified American South that appeared in the early nineteenth century. First, each of the Southern colonies confronted and competed with various Native and European nations for a sustained period of time. Native Americans and European settlers traded with one another, fought wars against each other, intermarried, created diplomatic alliances, and borrowed cultural traits from each other. This experience did not completely separate Southern colonies from those to the north. However, in the southeast, the confrontation between Natives and European newcomers was sustained over a much longer period. Where most New Englanders believed that the local Indians had either disappeared or been pacified by the end of the seventeenth century, Southerners dealt with the Five Civilized Tribes well into the nineteenth century. Even the history of forced removal in the 1830s did not eliminate the ability of some Cherokees, Creeks, Choctaws, and Chickasaws to fight for the Confederacy in the 1860s.

A reliance on the cultivation of a range of staple products also united the Southern colonies. In the Chesapeake region, tobacco provided a means for hopeful planters to recoup their early losses. In the Carolinas, indigo, deerskins, and later rice allowed the colony to flourish. Georgians found deerskins and rice to be their most important export crops.

Finally, all of the Southern colonies used systems of unfree labor to fulfill their labor needs. Indentured servants from England and Ireland provided most of the labor during the first sixty years of English settlement in the American South. After the 1660s, African slaves became the predominant choice of landowners for labor. Even Georgia quickly abandoned its restriction against slavery. This transition sealed the future of a multiracial South. South Carolina's black majority was not replicated in the other Southern colonies, but by the American Revolution slave populations had steadily increased in all of them.

The colonial South resembled its antebellum counterparts in numerous other ways. Both societies were violent, racist, patriarchal, dispersely settled, and rural. Most white residents lived as yeoman farmers or small independent planters, and most African Americans served as slaves on staple crop plantations. Political leaders in both eras received their privilege by birth, and the colonial varieties of labor systems paralleled those that would follow. Nevertheless, the American South in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries was still in the process of maturing. Little or no sense of a Southern consciousness existed in the colonial era, and during these formative years the territorial limits of the South constantly changed. Yet the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries contain hints of the Old South that would later flourish.

Shell gorget from the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex, c. A.D. 1000. A flying shaman with wings and talons of a bird of prey holds a human head in one hand.

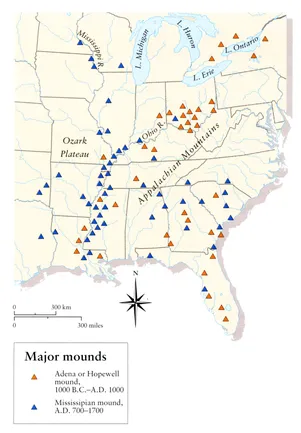

The Mound Builders

When European explorers traveled into the North American interior during the sixteenth century, they stumbled upon undeniable proof of ancient civilizations. Hernando de Soto, for example, encountered several large man-made earthen mounds during his journeys into the southeastern interior in 1539 to 1543. Later, in the eighteenth century, naturalist William Bartram observed that Cherokee Indians occupied some of these mounds. These structures filled the countryside west of the Appalachian Mountains and south of the Ohio Valley. Some were so large that their full size could not be determined until the advent of twentieth-century aerial reconnaissance. In size alone, these mounds impressed upon its visitors proof of a powerful and advanced people.

In the years that followed De Soto's travels, the earthen mounds in the southeast served as the focus of wonderfully imaginative myths and misperceptions. By the nineteenth century, Americans posited countless explanations for the presence of the mounds. Scholars and clergymen proclaimed that they had been built by one of many ancient groups, including the Egyptians, Trojans, Welsh, Norsemen, Spaniards, or even the survivors of the Lost Continent of Atlantis. Similarly, the Book of Mormon and other religious texts declared that the builders descended from the ten Lost Tribes of Israel. Some theorists insisted on the Aztec origins of the mounds. Rarely, however, were the Native Americans indigenous to the southeast seen as responsible for these remnants of a past civilization. They were believed to be too disorganized, uneducated, and uncivilized to build something so elaborate and technically sophisticated.

Modern scholars have dismissed the earlier myths about Indians that prevented their connection to the building of the mounds. Not surprisingly, modern archeologists have learned that the mounds were built by earlier generations of Indians hundreds of years before contact. Most of the Natives who built these mounds shared what is known as the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex, a group of shared religious beliefs and symbols held by many of the southeastern Mississippian people in the prehistoric period. Artifacts such as pottery and gorgets confirm that southeastern Indians shared similar ceremonial costumes, objects, and symbols. Many of these symbols are similar to those used in Mesoamerica and are associated with agriculture and fertility. The most pervasive of these symbols is a cross enclosed in a circle. Other symbols include swastikas, feathered serpents, human hands with eyes, circles with scalloped edges, spirals, human skulls, and forked eyes. The human figures depicted in the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex wear ear spools, necklaces made of conch shells, hair knots, tasseled belts, and aprons. The prehistoric southeastern peoples, although disparate in the languages they spoke and the structures of their societies, built the mounds in similar painstaking fashion—one basket of dirt at a time.

The peoples indigenous to the eastern part of North America built their earthen structures over a period of three thousand years. Many of the oldest mounds, built in the Woodland tradition (1000 B.C. to A.D. 700), served as burial sites. Some of the mounds built in the Mississippian tradition (A.D. 700 to A.D. 1700) served as foundations for the Native American's most important buildings. Most of these mounds were finished by A.D. 1300. They supported temples, mortuaries, and houses of powerful chiefs. Natives palisaded some mounds, built them near important waterways, and defended them with ditches and towers. Some mounds were rather isolated while others appeared to be precisely positioned with neighboring ones. Several had exact geometric dimensions, with circle-, square- or octagon-shaped embankments.

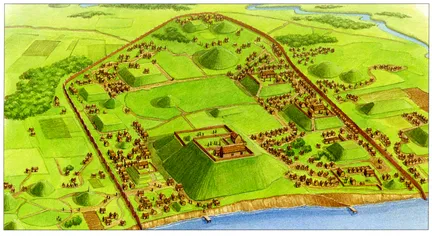

Occasionally, Natives built the mounds in clusters which became the ceremonial center for large chiefdoms. Perhaps the most impressive site is Cahokia. Located in present day Collinsville, Illinois, it served as the region's largest ceremonial and population center. Built around A.D. 700 and occupied for almost 600 years, Cahokia covered 5 1/2 square miles and housed nearly forty thousand inhabitants. It contained 22,000,000 cubic feet of earth, and the base of the structure was larger than the Great Pyramid of Egypt. Among the spectacular findings at this site, archeologists unearthed surveying equipment, proof that a wooden palisade of over twenty thousand logs encircled the entire site, and elite burial grounds. In addition, the mounds often included pottery, trophy skulls, a diversity of tools, baskets, gorgets, body adornments, smoking pipes, stone tablets, and animal masks. Monks Mound, a giant pyramid, stood in the center of the Cahokia complex. It rose 100 feet and had a base of 1,040 by 790 feet. Without question, Cahokia and the other mounds prove the vitality of the peoples and cultures that were destroyed by European contact.

Cahokia, as it may have looked about 1,000 years ago.

Indians and the Arrival of Europeans

In 1540, a southeastern chief struggled to describe what the arrival of Europeans meant to his people. "The things that seldom happen bring astonishment. Think, then, what must be the effect on me and mine, the sight of you and your people, whom we have at no time seen, stride the fierce brutes, your horses, entering with such speed and fury into my country, that we had no tidings of your coming." "Astonishment," he admitted, hardly approached the impact of what had happened. In the decades that preceded and followed this statement, the lives of Native Americans were turned completely upside down. Europeans may have "discovered" a New World in 1492, but the peoples that lived there for the past millennia watched their "old world" change so dramatically that it became a new world to them as well.

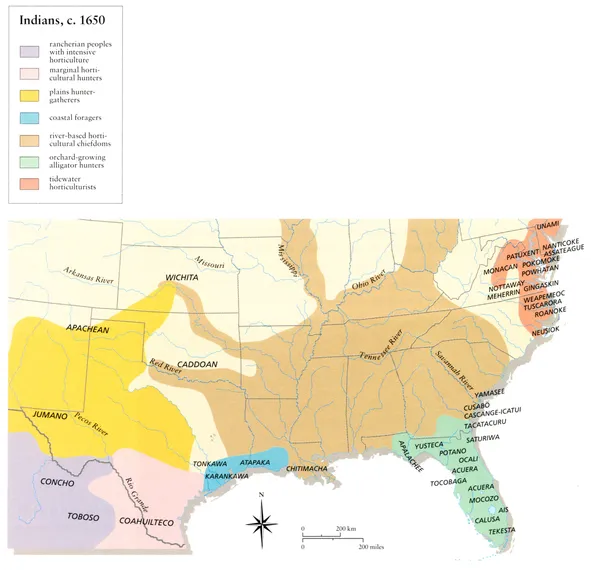

Before the sustained arrival of Europeans in the sixteenth century, an ethnic and cultural mosaic of nations and tribes covered the Americas. Internal differences outweighed any notion of a shared "Indian" heritage. The southeastern part of North America contained dozens of distinct chiefdoms. These complex Mississippian societies, which had formed several centuries earlier, generally contained paramount chiefs, hierarchical structures, institutions of centralized power, and specialized labor forces. These groups of southeastern Indians relied heavily on agricultural production, held diverse cosmologies, and competed for power and territory as distinct political entities. On the northern fringes of the southeast, near the Chesapeake Bay, lived somewhat smaller groups of Algonquian Indians. Like their southern neighbors, these Native peoples lived in towns governed by chiefs and practiced a combination of horticulture, foraging, and fishing. Unlike the Natives further south, however, they spoke languages from the Algonquian family and formed no large chiefdoms before European contact. Nothing united these diverse groups of indigenous peoples into a single entity. They spoke different languages, fought wars against each other, captured prisoners, and believed themselves to be different peoples and from superior civilizations. Only after the arrival of European explorers and colonists, and the tumultuous demographic consequences that ensued, did these disparate peoples become "Indians."

Pomeiockt, North Carolina. Between 1585 and 1587, while he was staying on Roanoke Island, John White made this watercolor representing the small Native American town located at the mouth of Gibbs Creek.

The population of North America at the time of European contact continues to elude precise assessment, but the population within the present United States in 1491 probably hovered around seven million. North America was not, as has been asserted, "virgin land" before the arrival of the European newcomers. The years that followed contact brought countless and dramatic changes for every Indian nation. Most important, they faced epidemics that ravaged their communities. Smallpox, measles, bubonic plague, and influenza reduced the population of the Indians of the southeast to a mere quarter of a million within a century. Indians had few effective responses to the diseases for which they had no immunity. Some ethnic populations were completely wiped out, while remnants of other communities struggled to survive. Epidemics continued to plague native communities long after the initial disruptions of contact. Georgia and Florida Timucuan-speakers and Texas Coahuiltecan-speakers, for example, survived the early waves of disease. But by the time of the American Revolution almost three centuries after contact, new waves of epidemics had wiped them out.

Demographic disruptions irrevocably altered Native societi...