![]()

Part I

From Coins to Crypto

In This Part

Chapter 1: Traditional Money

Chapter 2: Digital Gold

Chapter 3: Centralized Digital Payments

Chapter 4: Cryptocurrencies

![]()

Chapter 1

Traditional Money

Money is like muck, not good except it be spread

—Francis Bacon

Many books start telling their stories ab ovo,1 and this book is no exception. One can say that bitcoins are created from thin air. While perhaps it’s true, the idea wasn’t born in a vacuum. There was life before bitcoin, and its daring ancestors helped to build a foundation for what we recognize today as cryptocurrency. Learning more about the history of traditional and digital money and payment methods might help us to understand the common rules of the game and predict the challenges facing cryptocurrencies.

This book does not pretend to be a full reference on bitcoin design and implementation, but rather focuses on cryptography. However, it would be reckless to discuss other aspects of cryptocurrencies without reviewing its implementation, and especially without comparing this design with other cashless payment implementations, such as plastic cards.

Commodities versus Gold

Money. Everyone knows what it is, at least its practical application. It all began with barter, when people were exchanging their products with each other for goods and services. For a very long time barter was the only way to sell or buy. But at some point, people realized that barter was limited and inconvenient. For example, I have oranges that I want to sell, and I need to buy some apples. But the apple seller doesn’t need oranges, so I can’t buy his apples. In this situation, I need to exchange my oranges for something that would satisfy the apple seller as a medium of exchange for his apples. This something can be a commodity—goods that are useful to many people and that can be easily and willingly swapped for other goods and services. So commodities became the first money. For some time, many different societies were happy using commodities, such as cocoa beans in Abyssinia or iron nails in Scotland, as money.2 However, there were problems.

There are several important criteria for choosing a commodity to become money.3 First, the commodity should be in widespread use, or in heavy demand, so everyone would be willing to accept it as a payment for their goods. Second, it should be highly divisible so that it can be divided into small chunks in order to process micropayments, for example. Another important feature is portability, which, in most cases, is boiled down to the high value per unit weight. If money units with relative low value are too heavy, it is difficult to carry and transport them. In addition, a commodity must be highly durable so that it can be reused many times and stored for a long time as savings. Due to this last requirement, foodstuffs, for example, cannot be used as money. Another property, fungibility, means that different pieces of the material are equal, and can be equally interchanged. For example, pure gold is fungible, while coffee beans are not because they can be a different type, age, quality, weight, and so on. And finally, the commodity must have a limited supply in order to maintain its value, meaning that there should be no easy way to voluntarily add large amounts of money to the existing money turnover. Gold, silver, and other precious metals are rare elements and thus they ideally fit this requirement.

Table 1-1: Conditions for Accepting Commodity as Money

As you can see in Table 1-1, Bitcoin has much more of a chance to be accepted as money than coffee beans or salt; however, it still loses to gold, which is desirable by everyone due to historical traditions and physical characteristics.

Payment Cards

Electronic payments were introduced in the middle of twentieth century with the invention of magnetic stripe cards. Credit cards were the first application of plastic payment cards followed by various other types, such as debit, ATM, stored value, gift, fleet, and Electronic Benefits Transfer (EBT). Chip and PIN (EMV) transaction flow is similar to magnetic stripe cards, but EMV cards have an enhanced cardholder authentication mechanism based on cryptography thanks to a built-in chip.

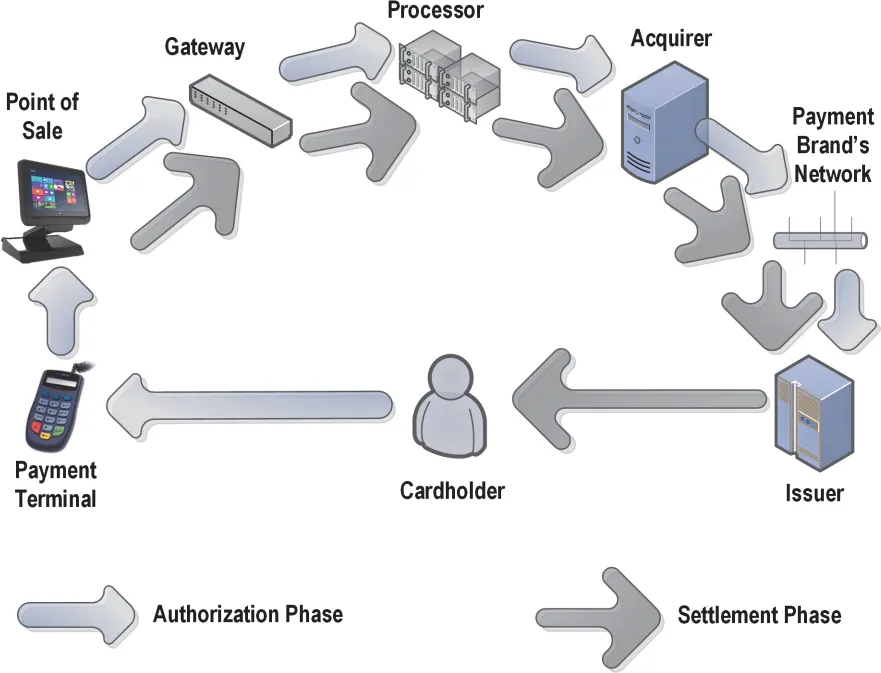

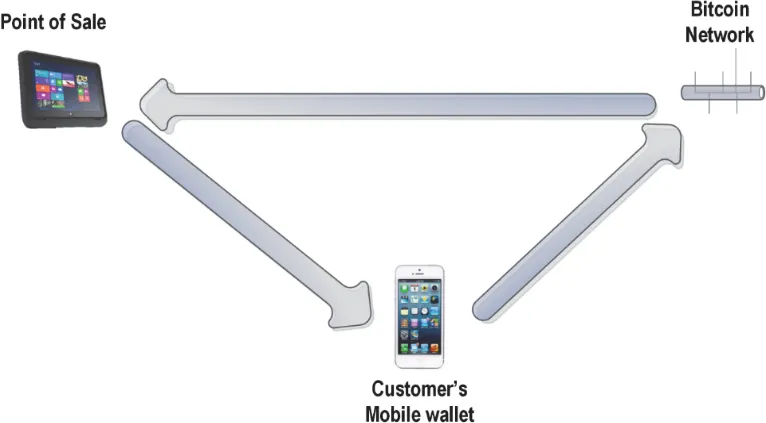

Plastic cards, both magnetic stripe and EMV, in a sense, are virtual digital money, but they are not a digital currency because they just provide an easier method of managing payments using the same traditional fiat currencies. However, there are multiple privacy and security issues and concerns associated with plastic cards.4 Therefore, the payment industry has long been in search of new, alternative methods of payments. It is possible that plastic payment card technology will be eventually adapted in some way to carry cryptocurrency and process crypto payments.5 But in any case, such a transformation would only preserve a facade that millions of consumers around the world find very convenient. Inside, plastic card processing is quite different from crypto payments, which might completely change the industry. Even after a very brief look at basic transaction flows (shown in Figures 1-1 and 1-2), without going deeply into the details, it is obvious that bitcoin payment processing requires less participants and therefore is less expensive.

Figure 1-1: Typical Credit Card Transaction Processing Flow

Figure 1-2: Basic Bitcoin Transaction Processing Flow

In a bitcoin transaction, there is no card issuing or acquiring bank and no payment processor or gateway.

Note: In fact, a payment processor is required in many cases in order to process bitcoin transactions between merchants and customers, especially in brick-and-mortar environments. However, a simple transaction between two individuals, for example, can be done using basic tools, without any intermediary, which is impossible in the case of credit card payments.

Nevertheless, credit and debit card payments still dominate the market of both offline (initiated in brick-and-mortar stores) and online electronic payments (although Internet transactions with credit cards are often processed through special online payment processors, which are discussed later in this chapter).

Mobile Payments

Even though mobile checkout is a very popular and promising trend, in most cases it is no more than just another extension of traditional fiat money that uses either the banking system or credit card infrastructure or both. Mobile payments usually introduce a new way of interaction between the customer and the point of sale (POS), with the same information being entered into the payment system (such as a token representing the banking account or credit card number). There are different technologies currently used to exchange information between the mobile wallet and the POS: Near Field Communication (NFC), barcode scanners, and even magnetic field emitters.6 One interesting implementation of mobile checkout is the Starbucks mobile payment app.7 It uses design principles similar to what I proposed in my 2009 white paper, “Mobile Checkout”.8 The app displays the QR code, which is scanned by the POS scanner, so the transaction is completed without physical contact between the customer device and point of sale.

Bitcoin mobile wallets also use QR codes to exchange data between the wallet and the point of sale, but the process that happens behind the scenes is completely different.

From Coins to Crypto

The chronology of world history shows that time is running much faster these days. If in the past there were hundreds or thousands of years between major inventions, nowadays major developments happen in a matter of a few years or even months. It’s not just intuitive assumption—in fact, there is a scientific theory and mathematical model that confirms these observations.9 Physicist and demographer Sergei Kapitza explains why historical periods eventually become shorter and shorter.10

At the beginning of humanity in the Lower Paleolithic, the interval for substantial change was roughly a million years. During the Middle Ages the period of change was a thousand years, and currently the period of change is only 45 years.

He says that the development of mankind seems to have sped up a thousand times from the Lower Paleolithic to the Middle Ages. This phenomenon is well known to historians and philosophers. Historical periodization should not be measured by astronomical time but rather by the proper time of the system. Such proper time is determined by the population growth: the more people live in the world, the higher the complexity of our system, and the faster it flows. If we assume that history is measured by the summary of human lifetimes rather than by the number of Earth’s revolutions around the Sun, the shortening of historical periods gets an instant explanation. At the beginning of the Paleolithic period, the population of our ancestors was only about a hundred thousand, so the total number of people who have been living during the Paleolithic period was about 10 billion. Exactly the same number of people has passed through the Earth for a thousand years of the Middle Ages and for 125 years of recent history. Nowadays, 10 billion people live on Earth during just a half-century. The entire historical era has shrunk to just a single generation.

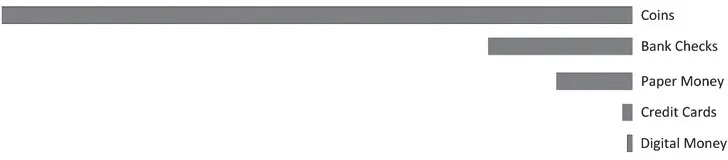

Figure 1-3: Time Intervals between Major Inventions in Payment Systems

Figure 1-3 shows the shortening time intervals between major events related to the development of payment systems. The first coins were created in Lydia (now Turkey) in sixth century BC. The ancient Greeks were the first society that accepted new inventions. In the Western world, it took more than a millennium until the creation of paper money in the seventeenth century. The first bank checks, however, were already in use by Italian banks in the fourteenth century.11 The automatic clearing houses started working in the 1970s. Diners Club created the first credit card in 1950. The first Internet payment system using “gold money”—e-gold—was introduced 46 years later in 1996, and then payment systems with the independent digital currency started right after it in 1999. And finally, the first crypto payment using the bitcoin network was performed in 2009, just 13 years after implementation of first online currency. We can see how time intervals between those major events in history of payments have been reduced from a magnitude of thousands to just a few years.

The first bank in the world was created by the Knights Templar, and it was active for almost 200 years until the full collapse of the Order of the Temple in 1314. But the failure of the first bank wasn’t the end of the banking system, which flourishes to this day. The first and once biggest bitcoin online exchange service, Mt. Gox, collapsed in 2014, just four years after it was launched in 2010. But the fact that its lifespan was so short does not necessarily mean that the entire bitcoin system is broken. It’s just that time runs faster according to the explosive growth theory.

Since creation of metal coins more than two and a half millenniums ago, new types of payment tokens and methods have not displaced their predecessors, but instead they just extend the assortment of possible tenders that can be accepted at the register. We can pay at the retail store using credit and debit cards, PayPal, and in some cases with bitcoin, but metal coins, paper banknotes, or bank checks still are very welcomed by merchants. Compare this with other technologies: once we started downloading movies online, we almost immediately forgot about DVDs (and video cassettes, respectively). The same...