eBook - ePub

The Efficient Market Hypothesists

Bachelier, Samuelson, Fama, Ross, Tobin and Shiller

Colin Read

This is a test

Share book

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Efficient Market Hypothesists

Bachelier, Samuelson, Fama, Ross, Tobin and Shiller

Colin Read

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Describes the lives, theories, and legacies of six great minds in finance who changed the way we look at financial markets and equilibrium. Bachelier, Samuelson, Fama, Ross, Tobin, and Shiller; proponents and critics of the market efficiency theories who redefined modern finance, creating the foundation on which all financial analysis rests.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is The Efficient Market Hypothesists an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access The Efficient Market Hypothesists by Colin Read in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Economic History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

This book is the fourth in a series of discussions about the great minds in the history and theory of finance. While the series addresses the contributions of significant individuals to our understanding of financial decisions and markets, this entry in the series describes a paradigm that was almost universally accepted by finance scholars upon its inception in the mid-1960s and questioned by financial practitioners ever since. We will describe the controversial efficient market paradigm and attempts by the finance discipline to make our financial models more realistic.

We begin with a description of one of the most profound contributions to finance in the twentieth century. Astoundingly, while this contribution was made more than a century ago at the very beginning of the twentieth century, the work of Louis Bachelier remained almost unknown for another 60 years until the finance discipline matured sufficiently to appreciate his insights. Many now acknowledge Bachelier as the father of modern finance, even though he never enjoyed such recognition in his lifetime.

We briefly covered some of Bachelier’s work in volume 3 of this series entitled The Rise of the Quants. However, while we noted that Bachelier also presaged the famous Black-Scholes equation by almost three-quarters of a century, he made another related contribution that was even more profound. He presented to us the random walk. Our realization of his contribution subsequently gave rise to a related concept, the efficient market hypothesis.

One of the reinventors of Bachelier’s work, the great mind Paul Samuelson, recognized the profound implications of the random walk and produced the theoretical justification of what we now call the efficient market hypothesis. While he qualified the usefulness of this hypothesis, later more empirically motivated commentators, especially the great mind Eugene Fama, were less circumspect. From it, Fama established for finance a mantra that has been quoted ever since – the principle that “security prices reflect all information.”

Others subsequently built upon the three-legged stool of the random walk, the efficient market hypothesis, and the notion of arbitrage upon which both arguments depend. For instance, the great mind Stephen Ross understood the interdependencies of these relationships to develop a more complete and useful extension of the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM), now known as arbitrage pricing theory. However, these new methodologies and paradigms, while intellectually rich, were inadequate to explain all the dynamics and gyrations of modern financial markets. The challenges of market bubbles and their collapses forced a new set of scholars, led by James Tobin and Robert Shiller of Yale University, to question conventional wisdom through both intuition and empiricism.

The final chapters on the efficient market paradigm are only now being written, though. These great minds have given us much intuition and many methodologies, and have motivated a whole new body of current and future research into behavioral finance. While this new field of behavioral finance will be left for a future volume, we cover in this volume the theories and criticisms of great minds in finance in informing the current cadre of scholars and practitioners alike. We will first cover the early life, and then the times, of these great minds because their life experiences informed their great insights. We will then describe their significant theory and insights into our financial decisions, followed by the various ways their insights were applied to benefit and, at times, challenge others. Each part will conclude with the reasons why various illustrious groups have recognized their contributions and their place in financial history.

In 1776, Adam Smith (1723–1790) published a treatise that created the discipline of economics. His Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations defined the notion of the invisible hand of economic activity. According to this paradigm, the enlightened self-interest of myriad independent producers and consumers provides the signals for production and consumption and allows market prices to adjust to equate these two sides of the market. Should there be a surplus, enlightened agents rid themselves of this excess by lowering prices, while shortages are addressed by a fictitious auctioneer who raises prices until more production is forthcoming and some consumption is curtailed.

Smith never described the actual dynamic process by which these prices adjust or how supply or demand is expanded or curtailed to establish or re-establish equilibrium. Indeed, the precise dynamics of this process remains vague to this day. However, the story Smith could tell was a simple one that entailed the entry of new producers when supply is short and their exit when there is excess supply.

All economists and finance students are schooled in this familiar story. The pursuit of profits drives such entry and exit until all profit opportunities are usurped. The great mind Kenneth Arrow’s proof of the existence of such a competitive equilibrium, and his extension of this concept to financial markets contingent on various future states of the world, forever enshrined this paradigm and has remained perhaps the most complete, robust, and widely accepted concept in all of finance and economics.

An analogy to this concept inevitably found its way into the theory of financial markets, even though it is inconceivable that financial markets could rise to the perfectly complete and competitive standard that Arrow envisioned. Instead of trading tangible goods between producers and consumers, traders of financial instruments are trading pieces of paper called securities with the expectation that the purchaser secures the right to a future flow of profits.

We shall see in this volume that there are extensions from the free market paradigm that make sense, and others that are much more subtle. It turns out that the concept of allocative efficiency in markets for tangible goods and services does not have a direct parallel in the information efficiency assumed in financial markets.

However, the compelling attractiveness of the argument that a financial security price should incorporate all available information through the twin forces of competition and arbitrage remains a cornerstone of modern finance, if not explicitly for some, then at least implicitly by most who cannot fathom the alternative. If securities prices do not incorporate all relevant information, the free entry of financial entrepreneurs, called arbitrageurs, would buy or short sell the mispriced assets under the premise that the market would eventually “get it right” and bestow upon these arbitrageurs profits for their courage and insight.

This logic is compelling. The discipline of finance assumes markets are information-efficient because to be otherwise would imply that there really is such a thing as a “free lunch,” a reward without the creation of anything substantial. Under the discipline of this logic, securities prices must logically reflect all available information, and any further fluctuations in prices must arise from unknown and reasonably unknowable factors influencing securities.

This logic spawned a great deal of subsequent empirical research which verified that any remaining price movements, once arbitrage has taken its course, must be random and indiscernible, as one would surmise if markets were informationally efficient.

Of course, some financial traders never troubled themselves with this financial logic. These chartists, or technical analysts, were too busy trying to glean tendencies in stock prices and realizing profits for their efforts – or at least so they would say. Practitioners of the other ilk, the fundamentalists, were trying to glean information unknown by others on the true underlying value of individual firms. These practitioners, too, believed that their creation of such private information, intelligence, or intuition was also rewarded with profits. Financial practitioners, divided into these two camps of the chartists and the fundamentalists, were united in their suspicion of the academicians who argued that both practitioner groups were claiming to earn profits that could not be earned in theory.

This is the story of the lives, times, insights, criticisms, and legacies of the great minds that created and fueled the debate over the efficient market hypothesis. We begin with the father of modern finance, and one who most students of finance know little about.

Section 1

Louis Bachelier: The First Physicist Financial Theorist

In the decades following the beginning of the Cold War, economics began its period of intense mathematization. Suddenly, with Harry Markowitz’s development of the Modern Portfolio Theory, and the extensions through the CAPM and the Black-Scholes equation, finance, too, became much more mathematics-intensive, just as physics had two centuries earlier. The end of the Cold War, the Space Race, and the arms race created a lull in the demand for rocket scientists and physicists and saw these theoreticians drawn toward finance and economics. The resulting drawing of physicists from a Space Race won by the Americans in the 1960s created a race for mathematical sophistication in finance in the 1970s. Many consider the 1970s to be the demarcation point for the foray of physics into finance. However, many now appreciate that the first mathematical physicist to contribute to modern finance was a Frenchman, Louis Bachelier 70 years earlier, at the tail end of the nineteenth century.

We begin with this first theorist who was able to translate the insights of those who came earlier with the mathematical rigor that would allow us to convert rhetoric and logic into science and mathematics.

2

The Early Years

There is some mystery surrounding the early life of Louis Jean-Baptiste Alphonse Bachelier. Our culture documents in great detail the lives of the famous, influential, and powerful. Less is known about scholars whose contributions are not recognized until long after they have passed. Bachelier’s story was further obscured because a fire destroyed some archives, because he departed early from the traditional upbringing of scholar prodigies when he was thrust into independent adulthood at too young an age, and because his life was punctuated by the chaos of two wars.

This we do know though. At an early age, Bachelier seemed destined for a prosperous and successful life. He was born into a family of some wealth. His maternal grandfather, Jean-Baptiste Fort-Meu, was a well-known banker and director of the bank la Compagnie des Caisses d’Escompte in Le Havre, and a minor poet. He raised a daughter, Louis’ mother, Cecile Gabrielle Adelaide Fort-Meu (1845–1889). Cecile was an articulate and educated woman who fell in love and married Louis’ father, Alphonse Bachelier, who was five years her senior, born on August 3, 1840 in Libourne, in the province of Gironde. Alphonse and Cecile married in 1867.

The young married couple settled in Le Havre, in the northwestern Haute-Normandie region of France at the mouth of the River Seine, where Alphonse maintained a successful family business. Then, as now, Le Havre was a bustling seaport, originally with the rest of Europe and then more broadly as trade routes expanded toward the West Indies and Central America. Alphonse was a wine merchant who represented the renowned Champagne vintner Mumm de Reims and the Bordeaux region vintner Balaresque in the export of their wines. He also acted as the director of the consulate on behalf of Venezuela. The family was well-to-do and there was an expectation that their first son, Louis Jean-Baptiste Alphonse Bachelier, would continue the family name, tradition, and business.

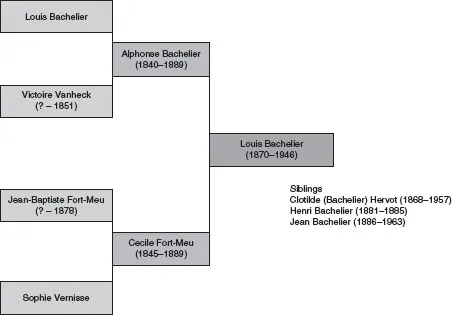

Figure 2.1 The family tree of Louis Bachelier (1870–1946)

Louis Jean-Baptiste Alphonse Bachelier was born on March 11, 1870 in Le Havre. His first name was taken from his paternal grandfather, and his middle names from his maternal grandfather and his father. Louis was preceded by his sister, Marie Louise Sophie Clotilde, and was followed by a brother, Henri, 11 years later and another brother, Jean Henri Etienne Francis, 16 years later. Henri died in 1885 at the age of four.

The family offered young Louis a stimulating upbringing. His father was an amateur scientist and shared with him an interest in mathematics and physics. Louis went on to study at high school (called the lycée in France) at nearby Caen, the capital of Basse-Normandie.

Louis graduated from high school in October 1888, just three months before his father’s death on January 11, 1889.1 Still reeling with the immense responsibility, at the age of 18, of maintaining his father’s business, Louis’ mother died less than four months later, on May 7, 1889. As the elder son, he was left to run the family company Bachelier Fils and to support himself, his older sister, and his three-year-old brother.

Louis juggled these premature burdens for more than two years before he was called to mandatory military service. The French had been concerned about the growing power and influence of the German Empire and had established compulsory military service in 1872. Military indoctrination was also common in public schools, and Louis was called to national duty at the age of 21. Some more affluent and influential families could arrange for their sons to avoid such service. However, young Louis had little such influence following the death of his father.

At the end of his military service, Bachelier enrolled at the Sorbonne in Paris. Meanwhile, he supported himself with various jobs that exposed him to the workings of the Paris Stock Exchange. Three years later, in what must have been an intense combination of study and self-support, he completed his Bachelor of Sciences degree at the Sorbonne. He continued his studies at the Sorbonne and completed a Certificate in Mathematical Physics less than two years later. He defended a thesis in applied mathematics less than three years after that, just after his thirtieth birthday.

Clearly, Bachelier was brilliant, but his studies were unconventional. He did not have the luxury of strict devotion to study without any material worries, as had many of his colleagues. On the other hand, he also gained a working knowledge of the function of one of the world’s leading financial markets, which was an appreciation none of his colleagues in mathematical physics could have gleaned.

From the academic record, it is clear that Bachelier struggled to garner the focus necessary to excel in mathematical physics in an era in which his chosen field was beginning a rapid acceleration in terms of sophistication. He had the opportunity to study underneath the brilliant French mathematician Jules Henri Poincaré, but he had to repeat at least one major progress exam in mathematics a number of times before barely passing it. Eventually, he managed to pass all the predicate exams and was afforded the opportunity to defend his thesis.

Many commentators have suggested the quality of his thesis defense as being at the root of his academic obscurity. However, the truth is more complex. In the French higher education system at the time, each mathematical physics program had two chaired professors – one steeped in the tradition of partial differential equations and the other more squarely in the study of physics. A thesis is usually more deeply immersed in one field or the other, and Bachelier proceeded accordingly. However, he had to also defend his understanding of the alternate topic not encompassed in his thesis. As stated earlier, he struggled in some areas and may not have excelled in this second part of his thesis. In grading his work, the thesis committee granted him the distinction of ‘honorable’, not the ‘tres honorable’ reserved for an excellent defense in both areas. However, his dubious distinction was not a comment on his innovative thesis.

This modest slight became significant because of the academic reality in France at the time that since each program had only two permanent chairs, new academic positions became available only through retirement. Without the thesis distinction of ‘tres honorable’, subsequent academic appointment would be difficult and academic obscurity in France at that time would be the more likely result.

We shall return to Bachelier’s lifelong frustration at a lack of academic recognition in his later life. With regard to the quality of the thesis itself,...