![]()

Chapter 1

Cradle of Chinese Cartooning

Dynastic Visual Humor and Narrative

Taking into consideration some of its characteristics, such as caricature, satire and parody, humor, wit and playfulness, and narration/storytelling, cartoon art existed in China thousands of years ago. It was not yet called manhua (cartoon); that term, meaning “painting with free strokes” or “drawing as dictated by a free will,” likely was first used in the eighteenth century to describe the exaggeration and satire found in painter Jin Nong’s “Mr. Dong Xin’s Inscriptions for Miscellaneous Paintings” (Liu-Lengyel 2001: 43; Barmé 2002: 91). Nor was it as conspicuously “cartoonish” in format and style as contemporary cartoons and comics, but the rudiments of the art form were definitely present.

Caricature

Exaggeration of facial and other bodily characteristics and grotesqueries have been found in Chinese art existent many dynasties ago. As early as the Yangshao Dynasty (5000–3000 BC), grotesque figures adorned burial materials; one burial jar of that period found in Shaanxi Province displayed a cartoon-like image of a human face (Li 1985: 20; quoted in Liu-Lengyel 1993). Also uncovered have been a number of stone statues and reliefs from about 1100 BC that featured humans in humorous ways (Lent 1999: 6, 8). For centuries, popular New Year’s pictures (nianhua), according to Bo (1995: n.p.), were “expert at using exaggeration and distortion to highlight forms.”

There have been those who disagree with the idea that China had caricature before the twentieth century, chief among them being A. L. Bader (1941: 229), who wrote, “The Chinese racial genius has always been for the indirect, for suggestion, for compromising rather than for outspoken from which caricature stems. Second, caricature demands freedom of expression…. Finally, caricature presupposes social and political consciousness in its audience.” However, evidence contradicts Bader’s assertion. Writing in 1877, James Parton told of a printer attached to an American mission in China who brought back a “caricature” showing an English foraging party that dated to the 1840s. Believing that the Chinese had been caricaturing for decades, Parton (1877: 196) wrote:

Caricature, as we might suppose, is a universal practice among them; but, owing to their crude and primitive taste in such things, their efforts are seldom interesting to any but themselves. In Chinese collections, we see numberless grotesque exaggerations of the human form and face, some of which are not devoid of humor and artistic merit.

Satire and Parody

For centuries, Chinese painters poked fun at the social and political systems under which they worked. As with artists of dissent in similar authoritarian circumstances, they veiled their meanings. Murck (2000: 2) reported that, in the eleventh century, “painted allusions to poetry became a vehicle for lodging silent complaint.” Drawn on scrolls, they were meant for private viewing to “empathize with those who had been punished, to ridicule imperial judgments, and to satirize contemporaries for the amusement and edification of a trusted circle of friends” (Murck 2000: 3). The ways that dissent was imparted varied; some scrolls illustrated the poem’s main point, while others either lyrically summarized a “revelation central to the referenced poem” or “treated visual imagery in ways analogous to poetry” (Murck 2000: 4). As an example of a “sarcastic quatrain” applied to a painting, Murck (2000: 127) showed a scroll of snails crawling up a wall, accompanied by these poetic lines:

Rancid saliva inadequate to fill a shell,

Barely enough to quench its own thirst,

Climbing high, he knows not how to turn back,

And ends up stuck on the wall—shriveled.

As Murck (2000: 127–28) explained, the poet, Su Shi, used the snail as a metaphor for Wang Anshi, a close advisor to Emperor Shenzong (1048–1085), “whose greed had over reached his inner resources. If the humor delighted like-minded men who were disgusted with ambitious officials, those who were the target of the jokes must have been infuriated. Both witty and accessible, the quatrains circulated widely.”

In the mid-thirteenth century, books of paintings with verse also had political allusions, some satirical in intent. Clunas (1997: 135–37) singled out Song Boren’s Meihua xishenpu (Register of Plum-Blossom Portraits) as a book with political allusions encoded in poetry. Meihua xishenpu supposedly was the earliest Chinese printed book in which illustrations did more than merely support the text.

Satire was plentiful in Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) paintings, Clunas (1997: 135) even claiming that the color that marked these works was for satirical effect. As an example, he said that the novel Jinpingmei (The Plum in the Golden Vase) was replete with color that described furnishings, architecture, clothing, etc., satirically implying that the owners of these things had no taste. Also in the Ming Dynasty (in 1465), according to Bi (1988: 1), an emperor “executed a royal masterpiece entitled Great Harmony, satirizing the bogus harmonious relationship among court officials.”

Zhu Da (1626–1705; pen name, Bada Shanren) and Luo Liangfeng (1733–99) are often cited as early Qing Dynasty painters who used political satire and caricature to make a point. A leading painter of his time, Zhu Da, because of his royal heritage, lived a precarious existence, hiding out in a monastery for decades until the uncertainty between the Ming and Qing (1644–1911) dynasties was settled. His “Peacocks,” drawn in 1690, displayed local government officials as ugly peacocks standing on an unstable egg-shaped rock as they waited for the emperor to pass by. Symbolically, the officials’ positions were portrayed as very shaky, despite their flattery of the emperor. Luo Liangfeng’s “Ghosts’ Farce Pictures” (about 1771) made fun of unacceptable human behavior of the Qing Dynasty.

Throughout the Ming and Qing dynasties, political satire in art was abundant, found in nianhua (New Year’s pictures), colored woodblock prints based on historical stories, folklore, and current events (Flath 2004). Wong (2002: 11) agreed that nianhua were often humorous or satirical, but, as she said, seldom were they political. However, New Year’s pictures of the late Qing Dynasty, according to Bo (1995: n.p.), often exposed the “grimness of society and even directly skewered the authorities.” Examples he provided were the Wuqiang New Year’s picture, “Pointy Heads (wicked and powerful people) Bring a Lawsuit,” which used “biting humor to render venal officials in sinister and diabolic form”; “The Ten Desires,” which ridiculed “avarice behavior”; and “Witticisms,” which satirized “degenerate worldly behavior.”

Humor, Wit, Playfulness

Humor and sarcasm figured in early Chinese stone etchings (shike), an example being an inscription found in Shandong Province, dating to the Eastern Han Dynasty (25–220), that pictured the tyrannical and licentious last king of the Xia Dynasty (c. 2070–c. 1600 BC) holding a spear while sitting on the shoulders of two women (Bi and Huang 1986). In at least one case, an emperor, Xianzong, made a humorous drawing for political purposes. The brush drawing, “Keeping Good Terms with Everyone,” appeared when Xianzong succeeded his tyrannical father in 1465; it was meant to lighten the public mood and announce that a different style of rule was on the way. The print showed three men’s faces on a common body; together, they formed a single smiling face that gave the impression that the men were holding one another.

In Chinese art, humor regularly has revolved around puns, wordplay, and connotative meanings attached to verses and other text accompanying drawings, and around folktales and artists’ philosophies. Even today, this is the case; to avoid trouble with authorities, artists employ traditional approaches of indirection and symbolism to “express satirical intent, inject humor in their art, or elicit a laugh or smile from the viewer” (Fu 1994: 61).

A figure very often used in traditional (and modern) Chinese drawings for humorous appeal is Zhong Kui, known as the “demon queller.” Supposedly, the character first appeared in a dream Tang (618–907) Emperor Ming Huang had while he had a fever. After Zhong Kui dispelled the fever, the emperor asked painter Wu Daozi to do a portrait of his healer (Forrer 1966: 66). Zhong Kui’s ugly face, heavy beard, and intoxicated demeanor have been the gist for many artists’ works since then.

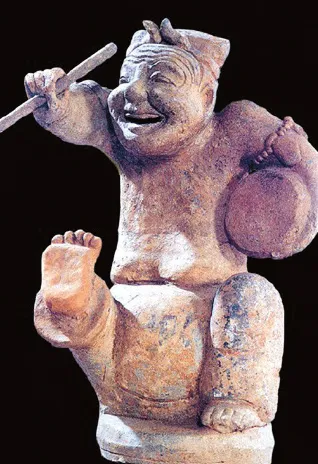

Fig. 1.1. Jigu shuochangyong (Drum Playing and Singing Figure), Eastern Han Dynasty burial tomb figure, happy to serve his master in the afterlife. Courtesy of Zheng Huagai. Zhongguo manhua (Chinese Cartoon), May 2005. http://www.ndcnc.gov.cn/jingpinzy/manhua.

Fig. 1.2. Jihuangpiao eyindan jingzhong (Hungry Men Eating Everything), North Wei mural in Ming temple built in 1503. Exaggerated depiction of one man holding a boar and biting its stomach; another with a whole bird in his mouth; others eating a man’s leg or chewing roots. Courtesy of Zheng Huagai. Zhongguo manhua (Chinese Cartoon), May 2005. http://www.ndcnc.gov.cn/jingpinzy/manhua.

Fig. 1.3. Humor played a pivotal role in early erotic art. This Qing print shows a young woman who has been stung by a scorpion while using the night chamber pot. Bertholet Collection in Dreams of Spring, 1997, 144.

Also exhibiting a great deal of humor and playfulness were the Chinese Spring Palace Paintings from the late Ming (from 1560 to about 1640) and succeeding Qing Dynasty, all erotic and irreverent. Many dealt with husbands getting caught while trying to seduce, or when copulating with, the servant girl or concubine; others portrayed a jealous child disrupting his parents’ love-making by pulling the father’s queue while the couple was entwined, a naked spouse trying to entice her studious husband to bed, a bashful bride wanting to escape the bridal chamber, or a fat lady bitten on her sex organ by a scorpion while using the chamber pot (Yimen 1997; see also de Smedt [1981]). The anonymous author of Dreams of Spring (1997: 43–45) pointed out that humor is an “important ingredient” of erotic art and that some popular booklets of late Ming “even become comics, where legends are added to the scenes.”

Narration/Storytelling

The tradition of telling a story with cartoon-like illustrations goes back to at least the Western Han Dynasty (206 BC–25 AD). A 1972 excavation found two picture stories on a coffin from that time (Zhu 1990). During the Eastern Han Dynasty, door gods (menshen) designed to ward off evil featured pictures of legendary heroes. Serial stories were prominently displayed on stone slabs and colorful frescoes during the Wei (386–534) and Sui (581–618) dynasties of the sixth and seventh centuries; they were usually interpretations of Buddhist scriptures or biographical sketches of Sakyamun (Peng 1980: 2). In 527, three episodes of Jataka stories were carved in a single sculpture of Jianbozhi; in 543, twelve episodes of Sakyamun were sculpted (Chen 1996: 66). Those that appeared during the Wei Dynasty were not fully developed as stories; that came about in the Sui Dynasty (Ah Ying 1982). Buddhist narrative paintings of the fifth through tenth centuries are plentiful in 492 decorated caves in Dunhuang, Gansu Province. The early caves depict narrative tales based on the lives of Buddha, illustrated for didactic purposes. Pekarik (1983: 24) said that some caves are both visionary and narrative, featuring “graceful elongated people, exaggerated swaying scarves and vividly colored bursting flames [that] give these paintings a remarkable sense of animation.”

Other forerunners of the modern serial story pictures can be found during the Song (960–1279) and Yuan (1279–1368) dynasties, when fictional works flourished. Artists were asked to decorate storybooks with illustrations at the top of pages; some from the Song Dynasty had cartoon characteristics (Shi 1989: 12). Also coming out of the Song Dynasty was Gengzhitu (Pictures on Farming and Weaving), first given to Emperor Ningzong and then successively carved on stone and woodblock prints. Gengzhitu and similar works aimed to increase productivity among farmers and weavers (Chen 1996: 72). Another Chinese painting of the tenth century, “Han Xizai yeyantu” (Han Xizai’s Night Banquet)—depicting five sequential pictures of the rich nightlife of government officials—has been labeled comic strip-like (“China’s Cartoon” 2008). In the Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties, popular romantic novels carried portraits of the main characters on the front and sometimes at the beginning of each chapter (Hwang 1978: 52). Some novels were richly illustrated with the upper half of each page featuring a picture or an illustrated page following every page of text (see also Chiang 1959).

Fig. 1.4. Laoshu jianü (Rat’s Quest for His Daughter’s Marriage), late...