![]()

1 Daydreams

JOHN TYLER WAS MIDWAY THROUGH A VERY LONG SPEECH in Richmond, Virginia, at one o’clock on the afternoon of March 14, 1861. Twenty years earlier Tyler had been president of the United States, and more recently he had been president of a hopefully styled Peace Conference that met in Washington, D.C., but he was not talking about peace, now. John Tyler was talking about the breaking up of the nation. Seven lower South slave states had seceded from the United States, and he told delegates from every county in Virginia, assembled in Richmond to deal with the secession crisis, about how and why the nation might soon break apart the rest of the way. He had talked on the previous day about differences between the Southern states, where slavery was legal and flourishing, and the Northern states, where slavery was not legal and the population was increasingly hostile to the South’s peculiar institution. John Tyler had talked for a long time on the previous day, and now he was talking again, his speech consuming a large part of one afternoon and more than two hours of the next.

Old and feeble, now, his voice weak and often inaudible, John Tyler nevertheless talked and talked and talked. He told the other delegates that the Peace Conference had failed to offer enough inducements to the politicians in the states that had already seceded to bring them back into the Union. At the same time, political leaders in the free states feared that it yielded too much to the slave states. Tyler had already explained that owners of enslaved laborers could no longer feel secure in taking their slave property into the western territories. Now he reported that the compromise proposals that came from the conference over which he had presided threatened to reduce, rather than to protect, slaveholders’ rights. Today, a month after the convention began, he talked about whether proposals to compromise the differences between the sections of the nation were genuine and hopeful or whether slave owners in the Southern states would be forced to yield to a Northern majority that seemed bent on preventing the spread of slavery into the western territories. That would bottle up slavery where it then existed, and the expense of feeding the surplus of laborers might actually destroy the institution that white Southerners were trying to preserve.

John Tyler was gloomy. Voters in the states without slavery had recently elected a president who made no secret of his distaste for slavery, the first such president in the country’s history, elected on a campaign platform that specifically demanded that slavery be confined within its existing borders. That president, Abraham Lincoln, had been inaugurated only ten days earlier. Those same voters, Tyler and his audience very well knew, might some day try to abolish slavery, the foundation stone of the South’s whole economy and society. John Tyler was very gloomy.1

A newspaper reporter took down Tyler’s words in Richmond’s Mechanic’s Institute, where the convention was temporarily meeting while the General Assembly occupied the legislative chamber in the nearby Capitol. Tyler later wrote out his report so that the whole speech, both days of it, could be printed in the newspapers. While he spoke, other convention delegates and ladies and gentlemen in the gallery strained to hear his words, not willing to wait for the published version, not wanting to miss the high drama of a former president of the United States talking about the very preservation of the nation. Some of them probably lost the thread of his argument or missed some of what he said. John Tyler’s voice was weak and often inaudible.

One of the delegates lost the train of argument entirely. He began to daydream, to think about his wife and children back home. George William Berlin, age thirty-six,2 had left them in the town of Buckhannon, in Upshur County, on the western slopes of the Allegheny Mountains. He missed his wife and his five little children, the eldest twelve, the youngest three.3 As John Tyler talked on and on and the background noise that filtered into the room from outdoors drowned out the old man’s feeble voice, Berlin began to daydream about his home and family. He finally gave up trying to follow what Tyler was saying and pulled out a sheet of paper on which he had written several paragraphs to his wife early that morning before the convention resumed its meetings at noon.4

He had written then about how the night before he and another delegate, who happened to be a brother-in-law of his wife’s brother, had sat up comparing notes on the beauties and excellencies of their wives. Both men missed their wives and families, and Berlin, at least, had already begun to regret that he had allowed himself to be elected to the convention and separated from them by too many miles and for too many weeks. He had finally received a letter from his wife, Susan Miranda Holt Berlin, who was a year or two younger than he, so he had learned a few days earlier that the mail had been robbed between Buckhannon and Clarksburg and that his wife’s letters, together with many others, had been destroyed or thrown to the wind after the thief did not find any money enclosed in them.5 He read his wife’s words of love and her repeated expressions of hope that he would return home safely and soon. It was one o’clock, and the convention had been meeting for an hour. John Tyler had been talking for most of that time.

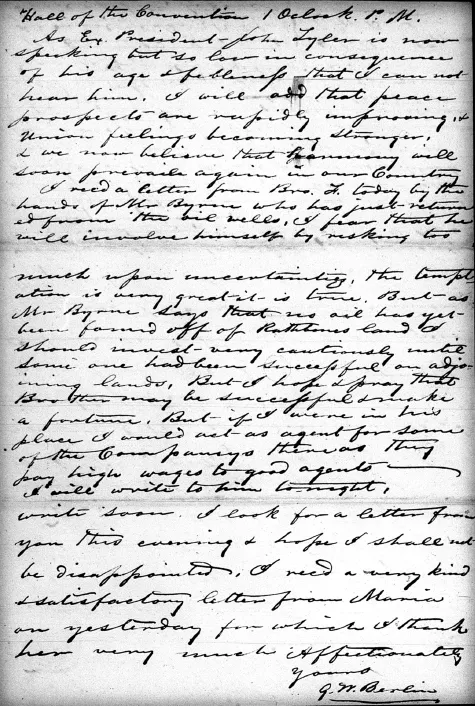

George Berlin inked his pen and began to write: “Hall of the Convention 1 Oclock. P.M. As Ex. President John Tyler is now speaking but so low in consequence of his age & febleness that I can not hear him, I will add that peace prospects are rapidly improving & Union feelings becoming stronger! & we now believe that harmony will soon prevail again in our Country.” Berlin had not been able to hear clearly, or his daydreaming had distracted him. He had evidently not been following Tyler’s speech closely enough to grasp the implications of what the former president was saying. Tyler was reciting a dreary list of capital failures in the nation’s most recent attempt to reach a compromise that would undo what extremists in the North and South had done. Seven states had seceded and organized the Confederate States of America. Such a thing was so difficult for Berlin and for hundreds of thousands of other Americans to imagine that in spite of the deep forebodings that ruined their digestions and their sleep, in spite of the very words to which they were listening as John Tyler talked on and on, in spite of everything, they could not believe that the United States would permanently fracture or plunge itself into civil war. The unreality of what they were hearing may have made men like Berlin tone deaf to the implications of Tyler’s words.

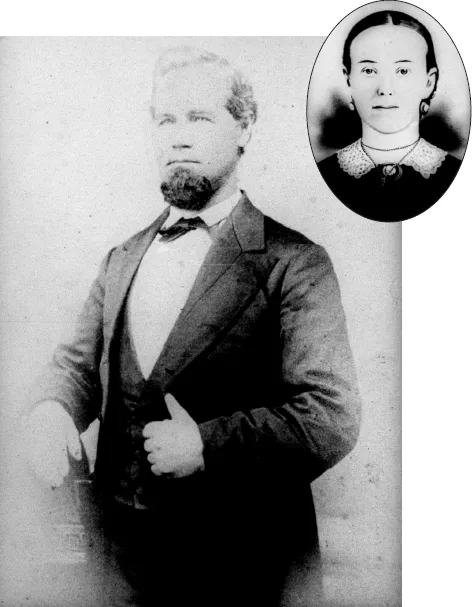

George William Berlin and Susan Miranda Holt Berlin (inset, in the only surviving photograph of her, perhaps the one she sent to him in January of 1862).

While Tyler talked, Berlin worried about whether he would get home in time to sow seeds in his vegetable garden, to plant some fruit trees, to see whether any of his neighbors had pilfered from the stacks of stone, brick, and lumber with which he was hoping to build a new and larger house for his family. He missed his family more and more every day as the convention dragged on and on. He thought about them often, wondering whether they were healthy and safe. He had not heard anything about them for more than a month after he had left home to attend the convention. Lack of news from and about his wife and children made Berlin worry even more. A few days earlier he wrote to instruct his wife to place the key of the upper room in the inside lock so that if fire broke out nobody would be trapped. A fire in Richmond had reminded him that the key was where he usually kept it when he was at home, not where his wife and children, who relied on him for protection, would be able to find it.6

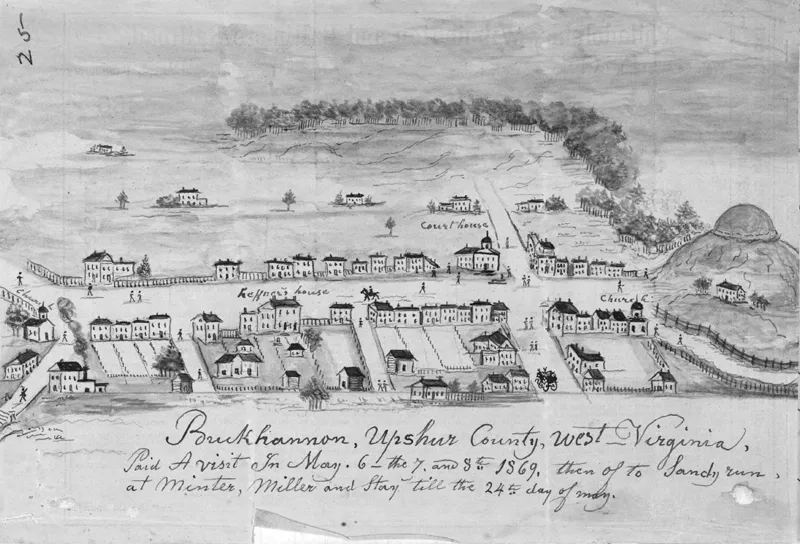

That day, as on other days, even as Berlin sat in his seat trying to listen to the speakers in the convention, he daydreamed about his family in Buckhannon. It was a busy town in a pretty place, taking its name from the little Buckhannon River, which, flowing north out of the mountains, had found or made a wide and relatively flat valley among the hills as it tumbled down toward the Ohio. The first settlers a century earlier had recognized a good town site when they saw it and put down their roots on the southwest side of a sharp right-hand bend in the river. By western Virginia standards in 1861 the town was fairly large, especially if compared with the little villages that dotted Upshur County’s forested hills and narrow valleys. Buckhannon had several hundred inhabitants, mostly clustered near the new courthouse or spread out along the river. The town had the usual compliment of merchants, cobblers, tinkers, blacksmiths, and school teachers, a couple of hotels that gave lodging to unmarried professional men, and a small number of attorneys to help keep track of all the land transactions and straighten out the many conflicts that a century of speculation and overlapping claims had produced.

Last page of George Berlin’s letter to Susan Berlin, March 14, 1861.

George Berlin was one of the attorneys. He had built or remodeled a house there in 1852,7 but it may have been damaged in a fire that destroyed a good deal of the town in October 1855.8 Now, he planned to build a proper new brick residence suitable for the successful young professional gentleman that he had become. Berlin owned four and a half acres of land on the opposite bank of the Buckhannon River in a big horseshoe bend that the river made, just as if it were lazily flowing through a flat delta and not through a mountain valley. A millrace closed the open end of the horseshoe, leaving the center entirely surrounded by water. Locals called it (and still call it) the island. Berlin had purchased a quantity of brick, stone, and lumber and stockpiled them there, intending to build a large residence for his family in the warm months of 1861.

As an attorney at law living in a bustling town, George Berlin was part of an increasingly numerous and important class of nineteenth-century Virginians. Professional men such as attorneys, physicians, clergymen, teachers, and merchants in Virginia’s towns and cities were the new class of civic leaders, replacing the tobacco planters who had dominated society and government during most of the previous two and a half centuries. In their towns and cities, the professional men and their families cultivated civic values, sang popular songs to the accompaniment of pianos in their parlors, read the latest national periodicals, and formed themselves into what elsewhere and in larger American cities would have been regarded as an emerging bourgeois community. Their perspectives and values were much the same as the perspectives and values of urban Americans elsewhere. They read the same national periodicals, dressed in essentially the same styles, and founded and supported temperance societies, religious organizations, and social service clubs. Even if they did not all recognize the fact, they were the emerging new leaders of Virginia.9 At the convention that George Berlin attended early in 1861, almost exactly two-thirds of the delegates were or had been practicing attorneys. The same had been the case in the state’s most recent constitutional convention in 1850–51,10 just as the same was the case in nearly every other American state at that time.

Buckhannon, Upshur County, drawing by Lewis Miller, 1871. (Lewis Miller Drawing Book, 1856–71, Mss5:10 M6155:1, Virginia Historical Society)

However difficult to imagine the possibility of disunion had been before the winter of 1860–61, it had become reality, and it had brought Berlin and 151 other Virginia men to Richmond for the convention. Opponents of secession, Berlin among them, held a large majority of the seats in the convention, and they hoped that once more, as in the past, some wise men could contrive a means of patching up the differences. It had happened before, and it could happen again. Back in 1820, just a few years before Berlin was born in Pennsylvania, Henry Clay and other members of Congress had compromised the differences that arose when Missouri applied for statehood, threatening to alter the national political balance between the states with slavery and the states without slavery. For the next thirty years the country thrived and grew. In spite of clearly widening differences between the region with slavery and the region without slavery, their differences did not tear the country apart. Indeed, in some respects the rapidly expanding cotton and sugar plantations of the South contributed significantly to the industrial and economic growth of the North and the whole nation. Compromise had been possible before, and compromise had worked.

Compromise had worked again in 1850 when Berlin was a young attorney in the mountains of northwestern Virginia. He had grown up in Pennsylvania and moved to Ohio, traveled as far west as the Mississippi River,11 and then returned to the east to teach school in Augusta County, Virginia. Quickly growing disillusioned with teaching, he moved into Staunton, where he and his brother Frederick Berlin studied law with a distinguished attorney, Lucas P. Thompson, and married sisters.12 Frederick Berlin married Maria F. Holt in 1844,13 and George Berlin married Susan Miranda Holt in 1846.14 They were two of the six daughters of Thomas Holt and Minerva Graham Holt, who lived on a farm in the northern part of Augusta County. Susan Holt was about twenty when they married, George Berlin twenty-one. He was admitted to the bar early in 1846 15 and not long thereafter opened an office in the town of Beverly in the mountains of western Virginia. By the summer of 1850 when a new sectional crisis arose, he had moved a few miles west to Buckhannon.16 George Berlin became an officer of and speaker for the Sons of Temperance; and his sister Catherine Berlin lived there, too, and taught school before she married.17

Berlin was a young man on the way up the social and professional ladders in 1850 when the nation faced another crisis about the admission of new western states following the war with Mexico and the rapid movement of thousands of Americans into the southwest and the Great Plains. Owners of enslaved people in the South believed that they had a right to take their slave property into the new western territories, where many of them expected to create new western slave states; but opponents of slavery in the North objected and tried to prohibit the spread of slavery into and across the Great Plains and to prevent the creation of more slave states. As before, Henry Clay and talented national statesmen had fashioned a compromise, one that did not entirely satisfy anybody, but one that satisfied enough people well enough that the country held together again.

Now, though, there was no Henry Clay. He had been dead for nine years. His death might have seemed to symbolize or foreshadow the end of nation-saving compromises. If the Great Compromiser—for that was the honorable title he earned in twice saving the nation—was dead, did that mean that hope of compromise was also dead? Virginians in Clay’s native state of Virginia, as well as most other Americans, hoped not. Virginia women who had been ardent admirers of Clay had raised a private subscription to erect a splendid, life-sized marble statue of Clay on the grounds of the Capitol in Richmond in 1860. The statue of Clay shared conspicuous place with another statue of an even greater patriot. The other statue was a spectacular greater-than-life-sized b...