Cryosphere

The cryosphere refers to the frozen water part of the Earth's system, including snow, ice caps, glaciers, and permafrost. It plays a crucial role in regulating the Earth's climate and is sensitive to changes in temperature and precipitation. The cryosphere also has significant impacts on sea level rise, freshwater availability, and global climate patterns.

4 Key excerpts on "Cryosphere"

- eBook - ePub

Applied Climatology

Principles and Practice

- Allen Perry, Dr Russell Thompson, Russell Thompson(Authors)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

...Likewise, water resources become critical under extreme climate conditions, especially when supply and demand lose their synchronization under drought episodes. Frozen water bodies (i.e. glaciers) are the true ‘progeny’ of climate which controls all their physical and thermal characteristics. For example, the conversion of snow to glacial ice and the mass balance of glaciers are critically related to climatic conditions (especially atmospheric heat transfers). The influence of climate on geomorphic processes and landforms is not so convincing since, at scales finer than the global or regional, generalizations about the role of climatic inputs in landform evolution have proved more difficult to sustain. The response of a landform to climate is known as landscape sensitivity and lowsensitivity landforms retain their characteristic forms mainly in response to local features and actual morphology, for example the supply of debris to rock glaciers. Over the past century, the above-ground climate has been accepted as one of the main environmental factors involved in soil formation. Soils and climate are indeed intimately interrelated and they bring together two of the most critical environmental parameters of life on the earth. The most important climatic elements are solar radiation, soil temperatures (which control chemical reactions and biological activity) and the soil moisture budget. However, it is evident from present-day soil classifications that there are important deviations in the relationship between soil patterns and climate data, since climate is only one of some five factors responsible for soil formation (Jenny, 1941). Also, soil zonations, based on present-day climate, do not necessarily reflect the conditions under which soils were originally formed, which could have been so different in the past...

- eBook - ePub

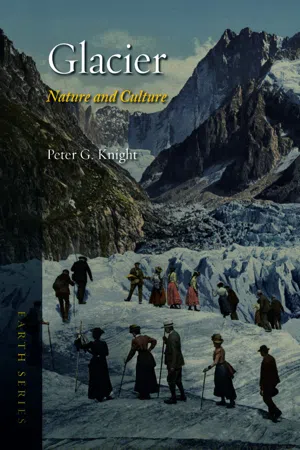

Glacier

Nature and Culture

- Peter G. Knight(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Reaktion Books(Publisher)

...The coast of Greenland is on the left of the image, and the ice-sheet surface is marked by meltwater lakes. Glaciers and sea level One of the environmental relationships most under scrutiny in the context of future environmental change is the relationship between glaciers and sea level. The growth and decay of glaciers – especially the world’s great ice sheets – are closely connected to rises and falls in global sea level. Glaciers are part of the global hydrological cycle. Water evaporates from the oceans and from the land, travels in the atmosphere, returns to the surface mainly as rain or snow, and makes its way overland or through groundwater back towards the oceans. Glaciers are part of the transport system between the atmosphere and the oceans, and a location for the storage of water. Roughly speaking, on a global average, water that travels through the system via rivers takes about ten days to make its way back to the sea. Water that follows a route going through a glacier typically takes, on average, about 10,000 years. Glaciers take water temporarily out of the cycle and delay its return to the sea. When glaciers expand and large ice sheets exist on the continents a lot of water is being held back from the oceans. When those ice sheets melt, a lot of water is returned to the oceans. At present, about 26 million cubic kilometres of water are locked up in glaciers, the vast majority of it in the Antarctic Ice Sheet. That is equivalent to a depth of about 65 m (213 ft) of water spread across the world’s oceans, and is one of the reasons that people are worried about climate change and the melting of ice sheets. There is a lot of ice, and as it melts it will release a lot of water. At the height of the last ice age about 20,000 years ago, when there were ice sheets over North America and Europe, the ice locked up in glaciers was equivalent to 197 m of water spread across the world’s oceans, and the sea level was more than 10 m (33 ft) lower than today...

- eBook - ePub

- David N. Thomas, David N. Thomas(Authors)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Wiley-Blackwell(Publisher)

...Each winter liquid water freezes curtailing biological activity and confronting communities with the challenge of surviving until the following melt phase. Nutrient conditions range from ultra-oligotrophic conditions in snow and ice to organic carbon rich in cryoconite material. For instance, in cryoconites holes, photosynthetic rates can be as high as 157 μg C l −1 h −1, relative to the overlying water with rates ranging between 0.34 μg C l −1 h −1 and 10.6 μg C l −1 h −1 (Säwström et al. 2002). Many microbial species found in glaciers and ice sheets appear to have a cosmopolitan distribution, and thus their presence might be a product of the long-term transport of cells. However, these habitats also have distinct microbial communities, with many organisms possessing the necessary adaptations that enable them to operate in extreme cold conditions. 6.2 The Biodiversity and Food Webs of Glacial Habitats Figure 6.5 shows the main habitats that are ecologically and biologically relevant in glaciers. Here we consider several supraglacial habitats (i.e. habitats on the surface of a glacier); these are ice shelves, cryolakes, cryoconites, wet ice surfaces, and snow. We then consider the englacial systems (i.e. habitats within a glacier) and subglacial habitats (i.e. habitats beneath glaciers). One of the main limiting factors for the existence of active microbial communities in an ecosystem is the presence of liquid water and the habitats discussed below contain sufficient liquid water to sustain microbial activity in glacial ecosystems. 6.2.1 Ice Shelves Both the Arctic and Antarctic have extensive ice shelves at their margins. Globally the majority of ice shelves are in the Antarctic. Most of our knowledge of the biology of Arctic ice shelves comes from the Canadian High Arctic (Vincent et al. 2004 ; Mueller et al. 2005 ; Bottos et al. 2008)...

- eBook - ePub

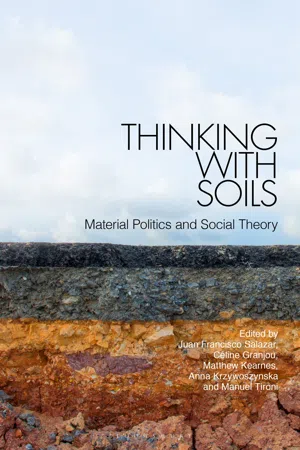

Thinking with Soils

Material Politics and Social Theory

- Juan Francisco Salazar, Céline Granjou, Matthew Kearnes, Anna Krzywoszynska, Manuel Tironi, Juan Francisco Salazar, Céline Granjou, Matthew Kearnes, Anna Krzywoszynska, Manuel Tironi(Authors)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Bloomsbury Academic(Publisher)

...2011). This is much less the case in the Antarctic than it is in the Arctic, where the dynamic instability of ice sheets, for instance, or the thawing of permafrost, become a code through which the political instability of the Arctic region can be grasped. As Bravo attests through his long-term work in the Arctic, “the melting of sea ice and other frozen states such as permafrost adds another dimension to the accelerated warming of the atmosphere caused by greenhouse gases” (2017: 27). However, as Bravo adds, “what hasn’t yet been adequately explained are the politics of frozen ecologies, and why they matter for the majority of citizens of the globe living in cities with no special interest in visiting the polar regions. Cryopolitics is the story of how the earth’s frozen states have come to matter in the age of the Anthropocene” (ibid.). We use the term “thermal geopolitics” as a framing device to examine how permafrost surfaces as a figure of both concern and hope in the northern polar region. Our discussion of frozen soils is attentive to what we call the everyday volumetrics of life and how it is being altered by thaw and melt. Sea ice and permafrost undergo seasonal thawing, which in many cases enables life forms to thrive and take advantage of summer light, open water, and additional moisture. Human and nonhuman communities, over millennia, have learned to work with what might be considered “normal” thermal regimes. Frozen soils are integral to “thermal geopolitics,” because the state of permafrost has shaped the scope and potential of settler colonial states such as Canada to “land” the northern fringes of the North American Arctic. Abnormal thawing poses existential challenges to not only smaller Indigenous/native settlements but also settler colonial infrastructures. In the Arctic, thawing permafrost is generative of disaster imaginaries, a new and unwelcome world where the effects of contemporary global warming are felt first...