![]()

1

International Economic Developments since the 1970s

Introduction

Financial deregulation that has taken place over the last quarter century has meant that large flows of funds can move quickly around the world seeking out the highest risk-adjusted return for investors. Real estate is increasingly seen as another asset that can be used in portfolios for diversification purposes, and a variety of investment vehicles in real estate have emerged. This book seeks to examine the financing of real estate investment and development within the context of an increasingly integrated international world economy and financial system. The approach adopted in the book is based on three questions:

- How real estate’s financial structure – the mixture of real estate financial instruments, markets and intermediaries operating in an economy – changes as economy grows and becomes internationalised

- How the developments in real estate finance – quality and quantity of real estate financial instruments, markets and intermediaries – impact economic growth

- How real estate’s financial structure influences economic development

The exposure of the financial sector to real estate has become clearly visible in the last few years. Linked to this, the international integration of the financial sector has also become highly apparent. The extent of financial integration and the scale and structure of the international financial markets today are significantly different from the 1970s when the earliest waves of internationalisation of real estate companies began.

In this chapter, international economic developments over the past 40 years are reviewed. This period is one of substantial change in the patterns of world trade and financial flows. Such change is set in the context of classical and contemporary trade theories. The globalisation of production and the increasing integration of different countries into the global system of trade are examined. This period also sees the development of world trading blocs such as the European Union (EU), the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and a more loose affiliation of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) together with Japan, South Korea and more recently China.

International trade theories: Setting the scene

In the asset market, investors invest in property in anticipation of realising returns. Property generates income (in the form of rent) and capital (in the form of change in capital values over time) returns for investors. Investors in the property asset market are both national and international. The nature of capital flows in property is of two types: (i) portfolio investment, where an investor resident in one country invests in stocks, bonds and other financial instruments related to property in the other country, and (ii) foreign direct investment (FDI), where an investor based in one country acquires property in the other country with the intention of managing it.

The development market is the market where developers combine land, material, capital and expertise to generate new space. Developers may be either national or international. In recent years, a number of international developers have been involved in development overseas. And finally, there is the user or occupation market. Their demand for space reflects economic fundamentals in that their demand is a derived demand for the use to which the space is put, being able to generate revenue from the sale of their product/service in the final market for goods and services. This occupier base may be local, regional, national or international.

There are three types of issues to consider: (i) internationalisation of economies through trade and FDI, which have implications for demand for real estate space; (ii) international capital flows in assets, including real estate; and (iii) internationalisation of real estate production processes and organisations. This chapter will explore various theoretical models that have been used in the economic literature to explain international trade in goods and services, capital and internationalisation of organisational structure.

International goods and capital flows

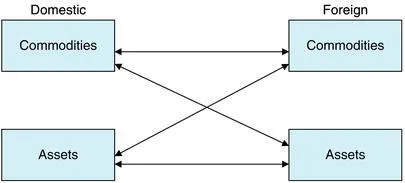

International trade in goods and capital flows are among the forms of transaction (other examples being trade in labour, technology, etc.) that take place between economic agents in different countries. Economic theory suggests that economic agents (consumers, producers, governments, etc.) can benefit from specialisation in production of certain commodities and exchange these ‘products’ for other goods and services. It is impossible for a country to be self-reliant without reducing its standard of living. There are three possible types of international transactions, as illustrated in Figure 1.1.

Residents of different countries could trade commodities for other commodities, or they could trade commodities for assets (i.e. that is for future commodities), or they could trade assets for other assets. All three types of exchange lead to gains from trade.

But, why does trade happen and how can trade between nations be explained theoretically?

Reasons for trade

There are five basic reasons why trade may take place between countries:

Differences in technology

Advantageous trade can occur between countries if the countries differ in their technological abilities to produce commodities. Technology refers to the techniques used to convert resources (land, labour, capital) into outputs. The basis for trade in this Ricardian trade theory of comparative advantage is differences in technology.

Differences in resource endowments

Advantageous trade can occur between countries if the countries differ in their endowments of resources. Resource endowments refer to the skills and abilities of a country’s workforce, the natural resources available within its borders (minerals, farmland, etc.) and the sophistication of its capital stock (machinery, infrastructure, communications systems). The basis for trade in this pure exchange model and the Heckscher–Ohlin (H–O) trade model is differences in resource endowments.

Differences in demand

Advantageous trade can occur between countries if demands or preferences differ between countries. Individuals in different countries may have different preferences or demands for various products. The Chinese are likely to demand more rice than the Germans, even if facing the same price. Scots might demand more whisky, and the Japanese more fish, than Americans would, even if they all faced the same prices.

Existence of economies of scale in production

The existence of economies of scale in production is sufficient to generate advantageous trade between two countries. Economies of scale refer to a production process in which production costs fall as the scale of production rises. This feature of production is also known as ‘increasing returns to scale’. This can also be linked to agglomeration economies in particular industries in certain locations (e.g. international finance in London or New York).

Existence of government policies

Government taxation and subsidy programmes can generate advantages in the production of certain products. In these circumstances, advantageous trade may arise simply because of differences in government policies across countries.

Differences in return on capital

Trade in capital may happen if the real return on capital across different countries varies. This may happen if demand for capital in present and future time periods differs among different countries.

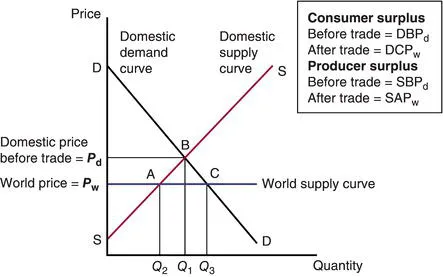

The main reason for trade to take place is that countries find it advantageous to trade. As mentioned previously, it is impossible for any country to be self-reliant without reducing its standard of living. This can be understood from the following simple illustration. Suppose that there is one good that the world produces and there is one good that the world consumes. This good can be produced by all countries; however, each country can decide whether to produce the good domestically or import it (partially or fully). Figure 1.2 presents the market equilibrium for the good under (i) no trade and (ii) trade scenarios.

In economics, the demand curve describes the quantity of a good that a household or a firm chooses to buy at a given price. Similarly, the supply curve describes the quantity of good that a household or firm would like to sell at a particular price. If demands of individual households in a country are aggregated, we can obtain an aggregate demand curve that tells us the total quantity of that good demanded at each possible price. Similarly, an aggregate supply curve would tell us the total quantity of a good that would be supplied by a country at each possible price.

Consider first the case of a closed country (which means that this country does not engage in trade with foreign countries). Figure 1.2 plots the price on the vertical axis and quantity on the horizontal axis. The downward-sloping line DD is the aggregate domestic demand curve for the whole country, and the upward-sloping line SS is the aggregate domestic supply curve. The point of intersection of demand and supply curve is the market equilibrium. This point determines the price that will be paid and accepted in the market. The point is labelled as B, for equilibrium, the corresponding price Pd is the equilibrium price, and quantity Q1 is the equilibrium quantity.

Now, suppose the country which was closed to trade opens its borders (removes restrictions that were not permitting trade to happen. Restrictions in the real world could take many forms, such as import tariffs, export restriction or quantity quotas) so that trade in goods and services can take place. The supply curve that the country faces now is the horizontal world supply curve. The world supply curve is horizontal because competition would prevent prices rising above this level. If prices rose, producers around the world would take this opportunity to expand their market and increase their production, thereby bringing the equilibrium price to Pd.

The supply curve that the country faces is not the original upward-sloping curve but the horizontal world supply curve. The demand curve, which depends on domestic preferences, does not change. The new demand–supply equilibrium will be at point C. Note that at this point the equilibrium price of the good is Pw < Pd. Consumers demand quantity Q3. What happens to domestic producers? Does production shift abroad? The answer to this question is complicated by political economy of trade and the extent to which trade is protected by the country. However, in the aforementioned example, when there are no restrictions on trade after the opening up of the economy, the domestic producers could supply goods at world price up to a quantity Q2 because their marginal cost of production up to Q2 is less than or equal to the world price. Above Q2, the marginal cost of production would exceed the market price at which goods can be sold (=world price), so that producers would find it unprofitable to produce. The country with demand Q3 would produce Q2 domestically and import (=Q3 − Q2) from the world market.

To understand the impact of trade on producers and consumers, let’s use an economic concept called ‘surplus’. Consumer surplus is the amount that consumers benefit by being able to purchase the good for a price that is less than they are willing to pay. For example, for all quantities supplied less than the equilibrium quantity, consumers are willing to pay higher than the equilibrium price. By paying equilibrium price, their surplus before trade is DBPd. The producer surplus is the amount by which producers benefit by selling at a market price mechanism that is higher than they would be willing to sell for. In the autarky (no trade) case, producer surplus is SBPd. Note that producer surplus flows through to owners of factors of production (labour, capital, land), unlike economic profit, which is 0 under perfect competition. If market for labour and capital is also perfectly competitive, producer surplus ends up as economic rent to the owners of scarce resources like land.

Let us see how trade affects the welfare of consumers and producers. The trade has opened up opportunities to buy goods at a lower price. For domestic consumers, trade is welfare enhancing. For domestic producers, however, the revenue has declined as they face price competition and find it unviable to produce more than Q2. Consumers’ surplus, which was DBPd before trade, has increased to DCPw. Producers’ surplus, however, has declined from SBPd to SAPw.

In...