Treasury Finance and Development Banking

A Guide to Credit, Debt, and Risk

Biagio Mazzi

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Treasury Finance and Development Banking

A Guide to Credit, Debt, and Risk

Biagio Mazzi

About This Book

Credit and credit risk permeates every corner of the financial world. Previously credit tended to be acknowledged only when dealing with counterparty credit risk, high-yield debt or credit-linked derivatives, now it affects all things, including such fundamental concepts as assessing the present value of a future cash flow. The purpose of this book is to analyze credit from the beginning—the point at which any borrowing entity (sovereign, corporate, etc.) decides to raise capital through its treasury operation. To describe the debt management activity, the book presents examples from the development banking world which not only presents a clearer banking structure but in addition sits at the intersection of many topical issues (multi-lateral agencies, quasi-governmental entities, Emerging Markets, shrinking pool of AAA borrowers, etc.). This book covers:

- Curve construction (instruments, collateralization, discounting, bootstrapping)

- Credit and fair valuing of loans (modeling, development institutions)

- Emerging markets and liquidity (liquidity, credit, capital control, development)

- Bond pricing (credit, illiquid bonds, recovery pricing)

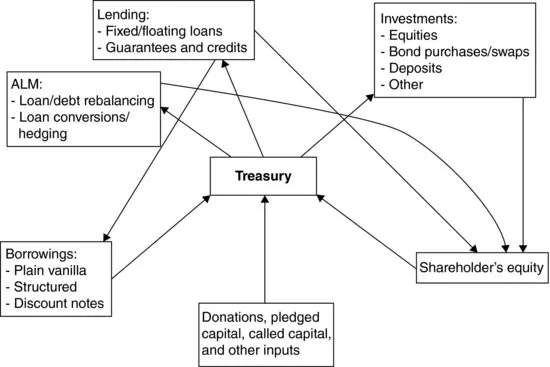

- Treasury (funding as an asset swap structure, benchmarks for borrowing/investing)

- Risk and asset liability management (leverage, hedging, funding risk)

Frequently asked questions

Information

- Loan versus credit or guarantee: The first choice facing a development institution offering financial help to a borrower is whether this help should take the form of a loan, a credit, or a guarantee. A loan is an instrument where the repayment of the principal is linked to some market-driven variable; we leave this vague but it means that irrespective of whether the interest rate is fixed or floating (see the following), it is driven by some market considerations. A credit on the other hand is an instrument where the repayment is usually made of a nominal (small) rate. Finally, a guarantee is not an offer of funds but a guarantee to honor a promise made by a borrower that an investor will purchase a bond issued by some country with the understanding that, in case the borrowing country defaults, the development institution wil step in to honor the debt. In general, the wealthier the borrower, the more likely it will be offered a loan rather than the other two instruments. Another general rule is that the size of a credit or a guarantee is usually smaller than the size of a loan.

- Bullet versus amortizing loans: A project that might be more or less capital intensive and it might offer returns in a more or less gradual way. A way for the lending institution to accommodate the needs of the client is to issue a loan with a specific repayment profile. A loan (we shall see this in more formal detail later) consists of a series of repayments of interest and principal, with the principal, as the name suggests, being the main component of the loan. Should the principal repayment prove to be difficult for the borrower, a solution is made available through a bullet loan in which the borrower throughout the life of the loan repays only the interest1 and the principal is returned only at maturity. Let us imagine that the borrower needs the funds to build up the country’s energy industry; these projects, ranging from dams to oil exploration, usually require a large initial investment, a long time to build, and then must produce a fairly regular source of income. During the build-up period it would be difficult for the borrower to repay the principal, therefore, in this situation, for example, a bullet loan would be ideal.A lender is, however, hesitant to issue too many bullet loans. This will be treated more formally when dealing with the issue of credit, but it is easy to see how the further into the future we push the repayment of the main part of the loan, the more—particularly when dealing with countries and projects fraught with uncertainty—we place ourselves in a riskier situation. Because of this, the more standard form of loan is an amortizing loan, one where, at each interest paying date, the principal upon which the interest is calculated is partly repaid.

- Fixed-versus floating-rate loans: The interest repayments on a loan are a percentage amount that can be either the same at each repayment date (a fixed-rate loan) or variable, linked to some external parameter (a floating-rate loan). The choice of loan on the part of the borrower and the lender will be mainly driven by considerations linked to the financial markets of the currency in which the loan has been issued. The volatility of interest rates and the expected levels of inflation, all compounded by the length of the loan, will be deciding factors in the choice. Similar to the previous situation in which the choice was about which repayment profile, the choice of fixity in the interest repayments will be a balance between the borrower’s needs and the lender’s ability to deal with financial risk. Development banks are typically very risk averse and will usually try to convert both costs (from their own borrowing, which we shall see later) and income (from loans repayments) into an easy-to-interpret and manage cash stream. Fixed- and floating-rate loans offer the lender different risk profiles with typically a preference for floating-rate loans.2

- The currency of the loan: An important issue is the currency in which the loan is offered, important also because the currency will decide which interest rate regime will govern the loan (i.e., if the loan is in currency X, it will be X interest rates that both borrower and lender will examine in their decision for a floating- or fixed-rate loan). The return on the investment the borrowing entity is hoping to obtain will drive, as it did in the previous cases, the choice of currency of the loan. We mentioned the example of oil extraction as a possible project: should the project be successful, the income generated will be in U.S. Dollars (USD) since oil is a global commodity priced in USD. The borrowing country will then be motivated to take a loan in USD. In the case, for example, of the construction of a dam to provide electricity to local customers (who are expected therefore to pay for consumption in local currency) the income generated will be in local currency and therefore the borrowing country would prefer the loan to be in local currency. We can easily see how from the borrower’s point of view it would be desirable to match, currencywise, the income stream with the debt stream.A similar and therefore symmetrical wish is on the lender’s part. Development banks are usually financed (as we shall see in the following section) in strong currencies3 and therefore would like to match the income they receive with the costs they face. A development bank would rather issue a USD loan than a local currency loan. Furthermore, a local currency loan is more subject to devaluation and/or inflation. An intuitive rule of thumb would be that anyone would rather receive income in a strong currency and pay debt in a weak one. As a consequence of this, local currency loans usually constitute a small, yet far from negligible portion of a loan portfolio.The needs of a borrower are assessed at the moment of deciding the type and amount of loan. It is considered that the borrower will face certain costs throughout the life of the project, and the loan should be used to cover those costs. These costs, however, could change dramatically—driven by changes in the foreign exchange—after the issuance of the loan and this is because of a third currency other than the strong and the weak mentioned before (e.g., the borrower needs to purchase equipment in a third country). To manage this type of exposure there are also multi-currency loans that are issued, linked not to a single currency but to a basket of usually strong currency.