eBook - ePub

Human Memory

Structures and Images

Mary B. Howes

This is a test

- 472 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Human Memory

Structures and Images

Mary B. Howes

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Human Memory: Structures and Images offers students a comprehensive overview of research in human memory. Providing a theoretical background for the research, author Mary B. Howes uses a clear and accessible format to cover three major areas—mainstream experimental research; naturalistic research; and work in the domains of the amnesias, malfunctions of memory, and neuroscience.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Human Memory an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Human Memory by Mary B. Howes in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Cognitive Psychology & Cognition. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Memory

Historical and Current Perspectives

Overview

1. Four historical traditions have shaped theories of human memory—namely, the Aristotelian (classic), rationalist, empiricist, and constructivist models.

2. The operation of computers has provided a fifth, recent model of human cognition and memory. According to this view, representations (concepts) consist of symbols.

3. The models outlined above have produced specific traditions of research. Empiricist thought led to the verbal learning tradition, founded by Ebbinghaus. A computer model, also influenced by empiricist tenets, led to the information-processing tradition. Researchers influenced by constructivism have focused on the issue of changes in memory and also on the role played by higher-order structures in memory.

4. Methodologies used in research into memory include experimentation, observational work, computer simulations, mathematical models, and neuroimaging.

Learning Objectives

1. Knowledge of the five major theories of cognition and memory and the fact that such theory shapes the nature of research. Theory determines what is researched and often the interpretation of the data.

2. Knowledge of the roots of current research traditions in the theories noted above.

3. Knowledge of the methodologies used to study memory.

There have been four great historical traditions concerning the nature of human thought. Each has influenced the way in which we understand memory. The recent development of computers has provided yet a fifth approach, which is now gradually taking shape in the form of theoretical models.

One issue concerning memory involves the nature of any content that we may recall. For instance, suppose I ask you to think of the concept DOG. You must retrieve this concept from memory. Then I might ask, What is the concept that you are now experiencing? What is it like? If you examine the material that is now in your awareness, you are likely to find an image of a dog. Is the dog concept, then, an image, and are memories in general, images? Perhaps. But suppose I then ask, Is a dog a living thing? The answer to this question cannot be found in the image, and yet I imagine that you will answer it easily. Does this mean that concepts consist of both images and some other kind of information? And if so, what is “the other kind”?

The theories described below all address this question, among others. But they are important for other reasons. The theories that we hold concerning memory directly shape research conducted into memory. They also play a major role in the interpretation of data. It is therefore of critical importance to understand the ideas that have framed the research covered in the present book. What follows is a brief description of some of the major issues.

1. The Classic Model: Aristotle

The Greek philosopher Aristotle (384–323 BCE) examined the question of memory in a brief treatise, translated into Latin as De Memoria et Reminiscentia, and later into English (Aristotle, 1941). It is strange to consider this, but almost all the principles concerning memory developed by European philosophers and later adopted by psychologists were first stated in this small body of writing.

Aristotle did not achieve such a level of sophistication working alone. He was the inheritor of an already well-developed history of philosophical examination, including examination of the nature of ideas, of memory, and of the role of function in both. His teacher, Plato (427–347 BCE) was engaged in all of these areas and developed metaphors concerning human recall. One was that memory could be likened to a piece of wax, on which impressions (the memories) could be made. In some people the wax was soft and would take the impressions well; in others it was harder and would imprint less readily and not retain the traces as long.

Aristotle not only thought in similar terms to some extent but also introduced ideas that far transcend any form of wax model. First, he noted that memory moves. When you remember one thing, you do not then sit with a freeze-frame picture of the thing. The content changes, and you either remember something else or think of something else.

This movement, Aristotle suggested, is not random. It obeys laws or rules. For instance, the thought or recollection of a given thing “A” will lead to the thought or recollection of another thing “G” if the two are similar to one another. On meeting a stranger, you might suddenly think of your cousin because the stranger looks like your cousin. Other such principles, according to the philosopher, included opposition, contiguity, and causal properties.

Contiguity involves a situation in which two things occur (or exist) together. If you constantly experience tables and chairs together, the thought of table will tend to activate the thought of chair—an outcome now known to occur when we free-associate. Perhaps the most surprising intuition here, however, involved the notion that causal relations guide memory.

If you see or think of an event, and that event will necessarily or generally lead to a certain outcome, you tend to think of (recall) that outcome—whether it occurs in front of your eyes or not. One of the most influential approaches to memory today includes this principle as a fundamental constituent of the model (Schank, 1982).

Aristotle wrote that memory frequently involves a kind of search. Here, you begin with one thought and may trace a path, based on the principles described above and no doubt other principles, between your starting point and the target memory. “One act of recollection,” he wrote, “leads to another,” in regular order (Aristotle, 1961, p. 612).

Aristotle also noted that when we recall memories, we experience images or “presentations.” But underneath these presentations lies something else, which might be described as abstract meaning. When I think of a dog, I not only see an image but am also aware of what a dog is, including the fact that it is a living thing. One of the major questions facing researchers (in the field of memory) today concerns the nature of this meaning content. How is it expressed? What is it?

Aristotle thought that all memory content involves presentations. This may be true. However, Sir Francis Galton (1879), much later, explored the issue of memory in a somewhat different way. He found that some individuals are high imagizers and see images when they think of entities or remember events. Others are low imagizers and generate little or no imagery when they think and recall. There’s probably a range of levels in between. Imagine your breakfast table as it was this morning. Do you see the objects on it? Or do you just “know” what was there? Or do you see a kind of schema or general image? Aristotle saw such things vividly—and always saw them. He appears to have been a high imagizer.

1.1. Meanings

Another of the great classic philosophers, Socrates (469–388 BCE) noted that we consider many things to be exemplars of the same idea, although they may not look or sound alike. And other things that do look or sound alike are not considered to represent the same concept. A worm and a crocodile bear little physical resemblance to one another, but we consider them to “be” the same thing in that both are animals. In contrast, an egg and a ping-pong ball look quite similar and certainly share many sensory features in common, but we consider them to be exemplars of different concepts. What then provides the basis for conceptual membership? Apparently, not appearance or feature similarity.

Some classic scholars believe that Aristotle answered this question (Randall, 1960). It is not clear that Aristotle intended to frame the issue in exactly the way that has been attributed to him, but his work can be read as expressing the following critical idea.

It may be that the nature or meaning of a thing is expressed in human cognition on the basis of the actions or functions that it can perform. For instance, the meaning of the concept “chair” reflects an object designed to allow a human being to sit down (with back support). Anything that possesses this function is a chair, regardless of what it looks like. The material of which it is made is also irrelevant. Thus, when I think of “chair,” I will not only see an image of a chair but also know what it is. The latter property involves the function described above.

By the same logic, a thing is an eye if it is structured in such a way as to provide sight (a function). Appearance, again, does not matter. The structure that provides sight to a fly looks altogether different from the structure that provides sight to a horse or a human. But they are all eyes, since all perform the same function. According to the Aristotelian view, the function that determines the meaning of a thing depends on it having an organization that would normally provide that function. For instance, a blind eye is still an eye because it is designed to provide sight. The fact that it has been damaged and so cannot actually perform that function, does not matter. The human mind identifies “potential function,” in addition to actual function.

The classic or Aristotelian view of meaning, described above, is supported today by philosophers within the neoclassic tradition. They have also extended the theory in several critical ways. Aristotle thought that there was one fundamentally important function that determined the nature of a thing. He called this its “form.” The form of an eye, for instance, would be the function of sight. This property wholly determines conceptual membership. That is, if a thing has a structure that provides sight, it is an eye and not a tree, a dog, or a table. Neoclassic philosophers agree with this claim, although the word used to designate it is now “core.” They believe, however, that the meaning of a thing does not only involve the core. Instead, the meaning of any given concept involves both the core and all other functions that members of the concept could perform (a chair could be used to prop open a door, for instance). The concept also includes general, nonfunctional information (chairs are found in houses) and, of course, perceptual information (Putnam, 1975b). Perceptual information reflects how a thing looks or sounds and any other relevant sensory properties.

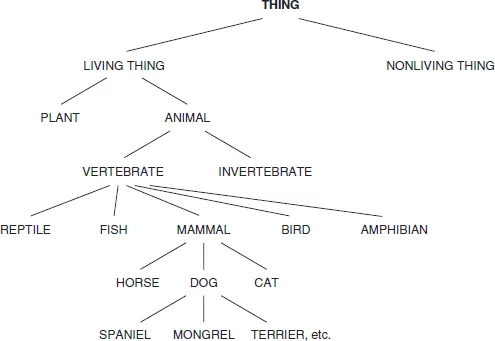

A final claim made by Aristotle that has considerable resonance in the field of memory today, is that human concepts operate in a hierarchy. Lower-level representations (an alternative word for “concept”) all have a meaning of their own. But they also include the meanings of all the conceptual classes directly above them in the hierarchy. Thus, a poodle is a dog, a mammal, a vertebrate, and a living thing. The poodle will inherit the core function of each of the classes above it. To put this somewhat differently, the meaning of “poodle” includes the meaning of mammal, vertebrate, and so on.

An example of the Aristotelian view of hierarchical concepts is provided in Figure 1.1.

2. Empiricism

John Locke (1632–1704) is generally identified as the founder of the empiricist tradition. In Locke’s day it was believed that ideas are innate. That is, we are born knowing what a dog, a cow, or the moon, is. The knowledge itself would be awakened or triggered in the child when a child first saw an example of the concept. Thus, the concept dog would be triggered when an individual saw a dog (or heard about a dog) for the first time.

Figure 1.1 An Example of Hierarchical Format in Human Concepts

NOTE: One set of nested classes (THING to SPANIEL) is shown.

Locke (1690/1956) rejected the innateness hypothesis. Obviously, he argued, we do not possess innate ideas. This would be like supposing you could know what oysters taste like if you had never tasted an oyster.

The philosopher suggested that we acquire our ideas through perceptual experience. The child see, hears, tastes, and so forth. Concepts are built of sense impressions. A sense impression is a unitary perception of some kind of, say, redness or roundness or a straight line, or a musical note. Our minds receive sense impressions and put them together into more complex unities (complex ideas). Conceptual representations are complex ideas. Thus, an idea can be described as an image—a kind of combination of sensory units.

Critical to the present theory, there is no direct, abstract knowledge in human thought or memory. All ideas and all mental content consist of copies of impressions received directly through the senses.

The model included the concept of an abstraction function, however. A child will see many trees, and the child’s mind will abstract out those sensory properties they all hold in common. These properties, combined, will constitute her idea, tree. This entity may be quite complex; it should probably not be equated with a straightforward picture of an average tree.

Locke described the mind as a tabula rasa, a blank slate, at birth. The mind writes on the slate on the basis of experience. All representation (a formal word for “idea”) is therefore, in one form or another, a copy of something derived through the senses.

The mind is nonetheless capable of deploying active mental processes, such as comparing objects, identifying relational properties, employing logical thought, and so on.

The philosopher assumed that mental content—ideas, thoughts, and memories—are built from an addition of units. The ultimate units were sense impressions, which could not be further reduced. A thought or a memory should be understood as the additive sum of its parts. Given this position, understanding a high-level form of cognition, such as a memory, depended on understanding the parts of the memory. The correct methodology would thus be to break the object of study down into its ultimate components. Thus, Locke advocated reductionism and the study of units as the correct methodological approach within this context.

Locke, as well as other empiricist philosophers, notably David Hume, believed that a fundamental principle in the organization of human thought and human memory was that of environmental contiguity. That is, if two things, maybe a knife and a fork, repeatedly occurred together in your experience—in the environment—they would become associated together in your memory. In time, thinking of (recalling) “knife” would lead you to think of (recall) “fork.”

Hume (1739/1965) wrote that thought depends on at least three major principles: resemblance (similarity), cause and effect, and contiguity of either time or place.

The empiricists believed that memories w...