eBook - ePub

What's Behind the Research?

Discovering Hidden Assumptions in the Behavioral Sciences

Brent D. Slife, Richard N. Williams

This is a test

Share book

- 264 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

What's Behind the Research?

Discovering Hidden Assumptions in the Behavioral Sciences

Brent D. Slife, Richard N. Williams

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This volume encourages students to engage in critical thinking by exploring the main assumptions upon which behavioral science theories are based and offering some alternatives to these assumptions.The text begins with a review and critique of the major theoretical approaches: psychoanalysis, behaviorism, humanism, cognitivism, eclecticism, structuralism and postmodernism. The authors then discuss the key assumptions underlying these theories - knowing, determinism, reductionism and science. They trace the intellectual history of these assumptions and offer contrasting options. The book concludes by examining ways of coming to terms with some of the inadequacies in the assumptions of the behavioral sciences.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is What's Behind the Research? an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access What's Behind the Research? by Brent D. Slife, Richard N. Williams in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

SAGE Publications, IncYear

1995ISBN

9781506319056

Edition

1

Introduction

Behavioral scientists, by definition, study and explain a broad range of human behaviors. However, if you ask a half dozen behavioral scientists how they would explain a friend’s rude behavior, you would likely get a half dozen differing replies. As the behavioral scientists consult the theories and models of their disciplines, they would offer explanations ranging from “she’s been conditioned by her environment” to “her more selfish id has overcome her more civilized ego” to “she freely and willfully acted rudely toward you.”

Explanations from the behavioral sciences can be so numerous that it is easy to get confused or frustrated. You might want to ask, “Just what is the right explanation anyway?” Most behavioral scientists would undoubtedly sympathize. Some would respond to your frustration by encouraging you to “tolerate the ambiguity” of behavioral science, because it reflects the ambiguity of life. These behavioral scientists have given up trying to discern the most correct theory or explanation. Other behavioral scientists, however, consider it part of their job to separate the theoretical wheat from the chaff and differentiate the bad from the good explanations. Many theories, they would say, can already be eliminated, because they do not measure up to certain standards. Other theories can be tested to see whether they hold up under the scrutiny of science or practice.

The problem is that these standards and this scrutiny do not typically expose the implicit ideas of the theories. All theories have implied understandings about the world that are crucial to their formulation and use. Even if we accept multiple explanations as the “way it is” in the behavioral sciences, this acceptance provides no means of recognizing the assumptions “hidden” in these multiple explanations.1 As students and consumers of the behavioral sciences, we accept and use theories that have important implications without recognizing those implications.

For example, the explanation you adopt for your friend’s rude behavior will affect the way you respond to her. Hidden in any of the differing explanations you can adopt is an assumption about determinism. Did forces out of your friend’s control, such as conditioning from her environment or chemicals in her brain, determine her actions? If your answer is yes, you might feel sorry for her and want to console her. After all, she could not help herself. If, however, you decide that she could have responded in a more polite manner—that is, her rudeness was not determined—you might be angry with her and wish to confront or avoid her. Your answer to this implicit question—whether or not you are aware of answering it—may result in a completely different type of interaction, if not a different future relationship, with your friend.

Discovering and understanding such implicit questions is the purpose of this book. In this book, we attempt to reveal what is implied by these theories so that students, practitioners, and teachers of behavioral science can make informed decisions about its strategies, techniques, and methods. It may be a very long time before behavioral scientists come up with a single theory that explains everything, if indeed this is ever possible. In the meantime, lay persons and professional people alike must adopt in their dally lives explanations and theories that have hidden costs and consequences. Therapists might not realize that the technique they use presupposes that patients are merely jumbles of neurons. Teachers might not know that an educational strategy they use assumes that students have no ability to make choices (even bad ones) in their learning. Managers might not understand that a business practice they employ presumes that clients have no feelings. The point is that all theories and strategies have ideas embedded within them that have very real and practical consequences.

Embedded ideas usually take two forms: assumptions and implications, the “from whence” and the “to whence” of theories. Theories must originate from somewhere, and the term assumption refers to the historical roots of a theory as well as the ideas about the world that are necessary for the theory to be true. For example, if you consider the environment to be responsible for your friend’s rude behavior, you are making the assumption of determinism. Theories must also lead us to somewhere. The term implication refers to the consequences that logically follow if the theory is put into action. For example, assuming your friend’s behavior is determined logically obligates you—for the sake of consistency—to a pattern of interactions that may include consoling her. The relation, then, between assumptions and implications is a logical one, “if_______, then_______.” If Assumption A is true, then Implications B and C follow.

The difficulty is that in the behavioral sciences, relatively little attention is paid to assumptions and implications. Students are often taught the various theories for understanding behavioral science phenomena, but rarely is this teaching enriched by directly examining the assumptions and implications hidden within these theories. Criticisms of the theories are sometimes offered, but these criticisms seldom do more than scratch the surface. Why? Why have behavioral scientists omitted discussion of implicit ideas?

In our view, this omission has rarely been conscious or deliberate. Rather, the omission has been due to other implicit ideas, particularly historical conceptions that have been accepted as true, necessary, and thus not in need of examination. This sense of security about assumptions has obstructed the complete examination of behavioral science theories. Therefore, before we can fully expose these assumptions and implications, we must first begin to understand why the implicit ideas have remained implicit. In other words, we must ask about the conceptual obstructions that have kept practitioners of sophisticated disciplines such as family science, psychology, education, sociology, management, and economics from examining the ideas underlying their most important and respected theories and methods.

OBSTRUCTIONS TO DISCOVERING HIDDEN IDEAS

As mentioned, many behavioral scientists have downplayed the importance of hidden ideas. Indeed, some behavioral scientists have denied the significance of theories altogether. For several reasons, which we briefly review here, these scientists have assumed that theories and their underlying ideas are secondary or even irrelevant to their professional activities. Your own associations with theories may be similar. For instance, it is not uncommon to hear someone say, “It’s just a theory,” and they say “theory” with a derisive, almost surly tone. What they usually mean, of course, is that the theory is “just” a speculation or an unproven hypothesis.

Scientific Method

This particular meaning of the term theory is derived from a widely held view of science. This meaning is important, because many behavioral scientists consider their discipline to be “scientific” in this sense. For them, theory is an educated guess about the world that must be held tentatively. The real solutions come only by using their scientific methods. Although many researchers consider this type of guess to be integral to science, theory is still viewed with suspicion until it is grounded in experimental data. Other scientists hope to do away with theories altogether. Their goal is to obtain all their knowledge from the cold, hard facts of science, with no theoretical trappings. This is a major reason that the implicit ideas in psychological theories have not received greater attention. Why spend time on the hidden ideas in guesses and speculations when the cold, hard facts are expected to provide the basis for, if not replace, the guesses and speculations?

One short answer to this question is that science itself is based on theories, or speculations. The method used to support or disprove other theories is itself a theory about how this supporting and disproving is done. Scientific method was not divinely given to scientists on stone tablets. There is no foreordained or self-evident truth about how science is to be conducted, or indeed, whether science should be conducted at all. Scientific method was formulated by philosophers, the preeminent dealers in ideas. These philosophers, not scientists, are responsible for the package of ideas now called scientific method. Scientists may use science, but they are often unaware of the ideas formulated by philosophers that lie hidden in their scientific methods. (Chapter 6 describes these ideas.)

This lack of awareness is partly because scientific method cannot itself be experimentally tested. Method has what some philosophers call a boot-strap problem. Just as those who wear old-fashioned boots cannot raise themselves into the air by pulling on the straps of their boots, so practitioners of the scientific method cannot use its methods to validate it. Some people argue that the many successes of science demonstrate its validity However, this argument contains the same bootstrap problem. Citing success begs the question of what one considers success and how one verifies it. Clearly these are speculative, theoretical issues. Moreover, success is not always an indicator of validity Hitler’s methods of social control were successful in the view of some people, though few would consider these methods appropriate now. Success may be in the eye of the beholder. Even if success were an indicator of validity, another more successful method might still replace it.

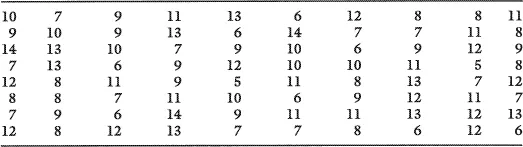

Table 1.1 Sample of Scientific Data

Scientific Facts

There is another reason we should spend considerable time on the hidden ideas related to science: The facts of science are themselves theory laden. A prominent misconception of scientists is that they are objective observers of the world. Although researchers use a theory-laden method, many people assume that scientists conduct their experiments in a way that permits the objective, nontheory-laden facts about the world to become evident. We could first ask how a theory-laden method could ever provide us with nontheory-laden facts. But even if we ignore this issue, we cannot ignore the necessity of interpreting the data yielded by scientific method. Table 1.1 provides us with an example of scientific data. As you can see, these data have little or no meaning without a researcher’s interpretation of them. We should also note that the source of these data—whether from biological, behavioral, or cognitive experiments—is irrelevant. The data still require interpretation.

In this sense, data can never be facts until they have been given an interpretation that is dependent on ideas that do not appear in the data themselves. Often these ideas are so hidden that scientists themselves do not know that assumptions are involved in their interpretation, or that interpretation is involved at all. Scientists may be so accustomed to seeing the world through their particular theoretical “glasses” that they forget they are wearing them. Make no mistake, however. Interpretation is involved in every understanding of data, and this means that the scientists’ unexamined views about the world inevitably enter into the “observed” facts. Even the statistics used to “interpret” data, as statisticians will tell you, have embedded ideas and assumptions. The point is that the so-called facts of science always have underlying ideas of the scientists mixed into them.

In sum, then, we cannot escape theories and ideas through science. If theories and ideas are speculative guesses about the world, then scientific method is itself a speculative guess about how one gains credible knowledge, because method is also a type of theory Because method cannot itself be validated scientifically, it must be evaluated through an examination of its hidden ideas, a task we undertake in this book. Further, the outcome of scientific method—the “cold, hard facts of science”—is not so cold and hard. The data that result from method are interpreted, and must be interpreted, by warm, soft human beings, who have biases and beliefs about the world that cannot be avoided. Many behavioral scientists may lament the necessity of interpretation, but there is a positive side. Interpretation brings human meaning to experimental data, talloring the sterile information of Table 1.1 to the particular context of real life. In this sense, escape from implicit ideas is not only impossible, it is undesirable. Any complete understanding or full use of the facts of science requires awareness of the ideas hidden within them.

Practical Motives

Does this same requirement extend to simple, practical uses of behavioral science information? “I want to help people,” one might say “and I do not see the need for an extensive understanding of behavioral science theories and their hidden ideas. Just have the scientists tell me what techniques work, and I will use those techniques to help people (in education, business, psychotherapy).” This raises the question of the technology of behavioral science. Should the behavioral sciences have technologists—persons who apply its information, but do not necessarily understand its theoretical grounding? A person who repairs television sets typically tests and replaces circuits without a full understanding of how the circuits work. Couldn’t a technological psychologist or educator work in much the same fashion? Although there is a sense in which the answer is yes, the difference between an inanimate TV and an animate human should make us hesitant to endorse this approach.

People are, after all, precious and unique. The potential risks and benefits of their “repair” are higher and less straightforward. This means that knowledge of implicit ideas is vital, because unexamined ideas can have important consequences for those to whom they are applied. Remember that any piece of information contains the biases of the information’s interpreter within it. Scientists may tell you that their particular ideas about the world stem from “previous research on the issue,” but such research itself is not without hidden ideas. Indeed, it is likely that the hidden ideas that led the scientists to interpret the previous research are still active and implicit in the present research. As we demonstrate in Chapter 6, there are always other ways of interpreting data, no matter how many data have been gathered.

To some people the task of helping others appears straightforward and simple—no theory seems necessary Although these people may be well intentioned, the outcome of their “helping” is often less than satisfactory This is usually due to their underestimating the role of implicit ideas. Often the goal of helping is more complicated than it first appears. For example, there are already ideas underlying their desire to help people. Some people desire to help in order to meet their own needs to be needed, rather than to meet the needs of others. At the very least, this leads to confusion about who is the helper and who is the one being helped. Even the goal of “making a person happy” is fraught with all sorts of theoretical issues. Some therapists claim, for example, that happiness is a poor goal, ultimately damaging many clients.

People with practical motives must therefore know the particular ideas that are concealed in the theories of helping they apply. Indeed, the case could be made that applied behavioral scientists—those in therapy education, and business—have a special responsibility to know the ideas embedded in this information. All people should probably be cautious about the information they use, but those who advise others have a unique responsibility to know the ideas implicit in that advice, whether the ideas originate from science or from the adviser’s own sense of things. If certain interpretations are wrong or harmful, then the appliers of these interpretations could harm, or at the very least, waste the time of many who receive these interpretations.

As an illustration, consider those who administered intelligence tests to U.S. immigrants of the late 1920s. At the time, this seemed like a worthy even altruistic task—preventing the “feebleminded” from entering the United States. Unfortunately an idea was hidden in these tests that led to some questionable, even harmful, practices.2 The idea was that intelligence is essentially the same the world over, regardless of language and culture. When some immigrants scored low on the test, the testers assumed that they were feebleminded or mentally retarded. As a result, they were denied access to the United States and often sent back to a country in which they were pol...