eBook - ePub

The New Sociology of Scotland

David McCrone

This is a test

Share book

- 736 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The New Sociology of Scotland

David McCrone

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Written by a leading sociologist of Scotland, this ground-breaking new introduction is a comprehensive account of the social, political, economic and cultural processes at work in contemporary Scottish society.

At a time of major uncertainty and transformation The New Sociology of Scotland explores every aspect of Scottish life. Placed firmly in the context of globalisation, the text:

- examines a broad range of topics including race and ethnicity, social inequality, national identity, health, class, education, sport, media and culture, among many others.

- looks at the ramifications of recent political events such as British General Election of 2015, the Scottish parliament election of May 2016, and the Brexit referendum of June 2016.

- uses learning features such as further reading and discussion questions to stimulate students to engage critically with issues raised.

Written in a lucid and accessible style, The New Sociology of Scotland is an indispensable guide for students of sociology and politics.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is The New Sociology of Scotland an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access The New Sociology of Scotland by David McCrone in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Regional Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 When was Scotland?1

This is a ‘sociology’ book, not a ‘history’ book, but arguably you cannot write one without the other. It is for historians to decide how much, or how little, sociology they wish to include, but beginning to tell the story of Scotland, as this chapter tries to do, cannot be done without history. In any case, we might ask: when does the ‘past’ end and the ‘present’ begin? We cannot understand one without the other. Arguably, the sociology of any society must involve telling its story, at least in terms of how its structures, social, political and economic, and its cultures were formed.

That, however, raises an important question: how much ‘history’ to include and how to tell it? Since publishing Understanding Scotland, first in 1992, and in revised form in 2001, there has been a huge increase in historical scholarship and output. Nevertheless, the task in this chapter is to sketch out a ‘sociological history’: to focus on the key events and processes which have shaped Scotland and formed it as a society. To that end, it is necessary to be selective. We will focus on three key points in history at which Scotland’s identity has been especially problematic and salient: (a) in the thirteenth century, and particularly relating to the Wars of Independence; (b) at the time of the Union of Parliaments with England in 1707; and (c) at the end of the twentieth century when agitation for greater self-government culminated in the recovery of a (devolved) Scottish parliament. Each time-point has as its central question: what is Scotland? Or, in the words of the chapter title, when was Scotland? How can we be sure that Scotland is meaningful in sociological terms?

Chapter aims

- To examine where the ‘idea’ of Scotland came from: what are its origins? In other words, when was Scotland?

- To discover what impact the Union of 1707 had on Scotland, its institutions and identity.

- To see how viable the arguments are that Scotland was ‘over’, that with the loss of formal independence it ceased to be a proper ‘society’, and that its culture was weak and divided.

In the subsequent chapter we will examine how the immediate history of the twentieth century shaped Scotland.

When was Scotland?

The historian Dauvit Broun has commented: ‘However old this fundamental sense of people [Scots] and country [Scotland] may be, it must have begun sometime’ (2015: 164). So when did ‘Scotland’ as an idea begin? Broun observes: ‘to insist that Scotland was not a meaningful concept, or that Scottish identity did not exist before the end of the 13th century, would surely be to allow our modern idea of Scotland to take precedence over the view of contemporaries’ (1994: 38).

So what is he alluding to? What we think of as ‘Scotland’ is shaped by our own experiences of it as a small, advanced, capitalist society on the fringes of north-west Europe. Trying to ‘imagine’ how our ancestors thought of it is much harder for us to do. Furthermore, there is an argument that notions of modernity so shaped our understanding of ‘nations’ that we simply have to treat them as modern creations.

We cannot know, the argument goes, what meaning and significance they had in the pre-modern era. Such is the view associated with Ernest Gellner, that the ‘nation’ is a cultural construction of modernity, dating from about the end of the eighteenth century. Gellner belonged to the ‘modernist’ school of nationalism studies, and Anthony Smith to the ‘pre-modernist’ one. In an engaging debate as to whether ‘nations have navels’, that is whether they derive from previous history or are simply creatures of ‘modernity’, Gellner and Smith argued whether modern nations have any or much claim to historic ancestry (see Gellner, 1996; Smith, 1996). All of this is part of a lengthy debate in nationalism studies about how old (or, indeed, how young) nations really are, and they have implications for Scotland.

Can we be at all sure that there is a clear historical lineage from past to present? We might take the view that our notion of ‘Scotland’ is a modern one, reflecting contemporary political and constitutional concerns, which we then read back into ‘history’, by way of ideological justification. We can use such justification for political purposes, to say, for example, that Scotland is one of Europe’s oldest nations, but can we be sure that our ancestors thought of it as a ‘nation’, and, if so, in what senses? Hence Broun’s comment that we cannot assume that the ‘Scotland’ we have inherited is that of the Middle Ages; that medieval Scotland means the same as modern Scotland. Much more difficult, then, as Broun observes, to ascertain whether people in the thirteenth century had any notion of ‘Scotland’, and what it might have meant to them. The author L.P. Hartley opened his novel The Go-Between (2004 [1953]: 5) with the words: ‘The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.’ His original manuscript continued: ‘Or do they?’, a question cut from the published copy. Perhaps we can reinstate Hartley’s question for the purposes of this chapter.

‘Not-England’

Why, you might ask, the thirteenth century? ‘Scotland’ might have existed as early as the first millennium, but it was the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, and above all the ‘Wars of Independence’ at the beginning of the fourteenth century, which arguably ‘made’ Scotland in a way we now recognise. This is territory belonging to medieval historians. Broun contends that: ‘it was not until the period between 1260 and 1290 that the idea of country, people and kingdom coincided to form what we recognise as the beginning of modern Scotland’ (2015: 165).

So what brought this about? Broun argues that this was the outcome of a long process which had its origins in England, rather than Scotland. This was the unintended consequence of legal and administrative reforms between 1154 and 1189 during the reign of the English king Henry II: ‘the main spur towards beginning to regard the Scottish kingdom as a single country may have been an intensification of royal power not in Scotland, but in England’ (2015: 167). In other words, Scotland developed a sense of itself as ‘not-England’, at the point where regal authority south of the border was flexing its muscles. Not to be incorporated into England required active dissociation. In any case, by the 1180s we have the earliest indications that local lords thought of the Scottish kingdom as a land with common laws and customs, an unintended consequence of comparable legal and administrative reforms in England during Henry’s reign.

By the middle of the thirteenth century, we have evidence of legal mechanisms in Scotland about the reporting of local land inquests to the king. Furthermore, the amount of money in circulation grew dramatically between 1250 and 1280, which was reflected in the creation of coinage mints from Inverness to Dumfries, as well as establishing sheriff courts throughout the land, both indicating jurisdictional expansion by the Crown.

We might assume, then, that the Crown was mainly responsible for shaping and imposing national institutions on ‘Scotland’, much as the monarchy did in France (Beaune, 1985). Broun argues that ‘Scotland’ came to be a phenomenon of the mind, an ‘idea that, at some point, came to be thought of by its inhabitants as one-and-the-same as the kingdom they lived in’ (2015:164). Furthermore:

When economic growth and the increasing importance of burghs is combined with the change in the procedure for inquests … it may be envisaged that those with property and possessions came more and more to identify with royal authority as a key background element in the pattern of their lives. (2015: 170)

Where was Scotland?

‘Scotland’ was envisaged in the twelfth century as the territory between the River Forth in the south, the Spey in the north, and the mountains of Drumalban in the west. However,

by the late 13th century, a new sense of kingdom, country and people emerged which, of necessity, was based on something other than the logic of geography. At the end of the 12th century the kingdom was seen by contemporaries as comprising several countries, with the Scots identified as the inhabitants north of the Forth. … this had begun to change by ca1220 when ‘Scotland’ appears to have meant the kingdom as a whole. By the early 1280s at the latest, not only had kingdom and country become one, but all its inhabitants were now Scots. (Broun, 2013: 6)

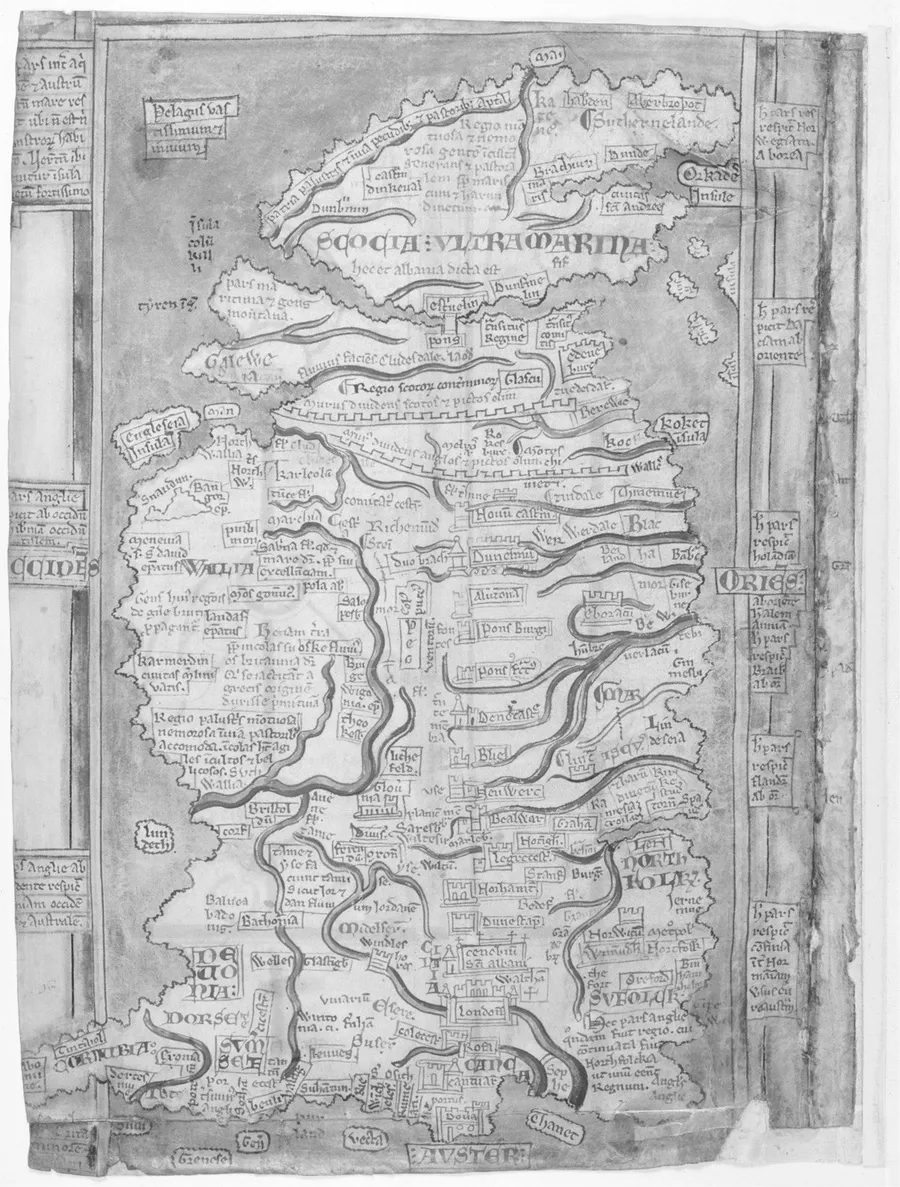

So strong was the conception of Scotland north of the Forth that it was thought of as an island, crossed by the bridge at Stirling (see map in Figure 1.1), which became a key battleground during the extended Wars of Independence.

Note, as shown in Figure 1.1, how the River Forth was imagined to be a continuous sea loch between east and west, with a single river crossing at Stirling (top, centre). For good measure, there are two walls dividing Scocia and Anglia, one, southern, approximating to Hadrian’s Wall, and another emerging at Berwick in the east, north of the River Tweed.

Figure 1.1 Matthew Paris map, fourteenth century

Source: Copyright British Library Board

Those described as ‘Scots’ (Albanaig) north of the Forth were later described as ‘highland Scots’, reflecting territorial expansion and diversity in the later period. Broun points out that the monks at Melrose (‘chroniclers’), who derived authority from the king,

may have become Scots, but this does not require that they ceased to be English. It depended on context. This ‘new’ kingdom-centric Scottish identity was grounded in obedience to the king of Scots. It is conceivable, therefore, that people continued to regard themselves as ‘English’ in the sense that their mother tongue was English, and at the same time identified as Scots. (2015: 168)

From the thirteenth century those living south of the Forth began to see themselves as ‘Scots’ living in ‘Scotland’, even if, like the Melrose monks, they viewed the northerners as somewhat unsavoury. Broun concludes:

Overall … we seem to have kingdom, country and people coalescing round the image north of the Forth as an island, an image rooted in an awareness of a genuine topographical barrier. By the late thirteenth century kingdom, country and people has coalesced anew around the dawning concept of sovereignty. The sense of ultimate secular authority shared by both had moved its centre of gravity from geography to jurisdiction. (2015: 186)

Thus did kingdom/country/people coalesce imperceptibly into a new ‘Scotland’ as an independent realm, a view shared by its people at large.

Who were the Scots?

What we have inherited is the characterisation of Scots as a ‘mongrel people’, no pure race, but an amalgam of peoples united by territory rather than ethnicity. Scotland has no ambitions to be pure bred: we are a mongrel people, at least in our conception of ourselves. Such a descriptor has appeal to politicians. Thus, Alex Salmond in a speech in 1995:

We see diversity as a strength not a weakness of Scotland and our ambition is to see the cause of Scotland argued with English, French, Irish, Indian, Pakistani, Chinese and every other accent in the rich tapestry of what we should be proud to call, in the words of Willie McIlvanney, ‘the mongrel nation’ of Scotland. (Speech to the annual SNP conference, Perth, 1995; quoted in Reicher and Hopkins, 2001: 164)

The conventional historical wisdom (e.g. Mackie, 1964), now disputed (Broun, 2013: 280), is that there were five ‘founding peoples’: the Picts in the north and east; the Scots around Dalriada in the west; the Britons in the south and west; the Norse in the northern and western isles; and the Angles in the south-east. Medievalists like Broun (2013: 276) are critical of this view, pointing out that it fits a narrative showing that they were inexorably united, by conquests or by dynastic unions, in order to conform to a conventional storyline.

Nevertheless, it helps to convey what the historian Christopher Smout memorably called a ‘sense of place’, rather than a ‘sense of tribe’. This is no claim to be morally superior to any other people; it was simply realpolitik. Thus:

If coherent government was to survive in the medieval and early modern past, it had, in a country that comprised gaelic-speaking Highlanders and Scots-speaking Lowlanders, already linguistically and ethnically diverse, to appeal beyond kin and ethnicity – to loyalty to the person of the monarch, then to the integrity of the territory over which the monarch ruled. The critical fact allowed the Scots ultimately to absorb all kinds of immigrants with relatively little fuss, including, most importantly, the Irish in the 19th century. (Smout, 1994:107)

This fitted in with how other historians made sense of the history of these islands. In many ways, Scotland was less homogeneous culturally and linguistically than its Celtic neighbours. The historian Sandy Grant observed:

during the Middle Ages the Welsh and the Irish surely had at least as strong a concept of racial or national solidarity as the Scots, and much more linguistic solidarity. Yet, between the eleventh and the thirteenth centuries, the whole of Wales and very substantial parts of Ireland were conquered by the English; subsequently both countries experienced many anti-English rebellions, but neither was ever liberated from foreign rule. The contrast with what happened to Scotland is obvious, and demonstrates that success or failur...