Why lost eras occur

While awareness of the existence of lost eras is crucial for investors, it is only the first step. A much bigger challenge is explaining why these periods of equity famine actually occur in the first place. Today’s lost era in the West began in 2000, with the bursting of the technology bubble. One possibility, therefore, is that previous lost eras were also at least partly the result of bubbles having burst.

Bubbles

The mania for technology, media and telecom stocks that began in the late 1990s was a clear example of a bubble even before it burst – at least to the more far-sighted among investors. The NASDAQ 100 index – home to many firms from the hot industries of the day – soared by an incredible 1,092 per cent from the start of 1995 to its peak five years later. Such perpendicular gains are themselves often a warning sign that things are getting out of control.

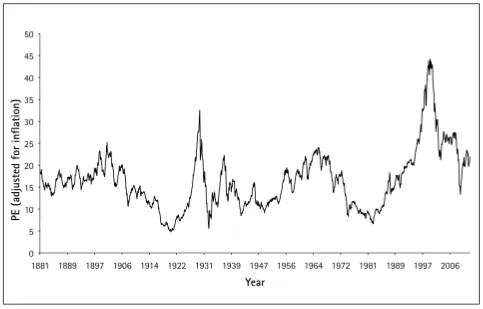

Of course, spectacular stock-price increases can sometimes be justified – particularly if corporate earnings are growing at a similar pace or are projected to do so with good reason. But it is hard to argue that this was the case for the late 1990s. Not only did the US stock market as a whole reach its most extreme ever level of valuation in terms of earnings, but many of the favourite hi-tech companies of the day did not have any earnings – or even revenues, in certain cases.

To justify this orgy of speculation, enthusiasts claimed that the game had fundamentally changed. New technologies – such as the internet – were supposedly going to improve the economy’s potential to grow forever. Turning received wisdom on its head, equities were even argued to be less risky than government bonds, rather than more so. And conventional cash-flow based techniques were abandoned and even ridiculed as being outmoded.

Aside from the vertical increases in stock prices and the fanciful arguments that the old rules no longer applied, other prominent bubble characteristics were clearly in evidence in the late 1990s. Edward Chancellor – a leading authority on financial-market manias – has listed other generic features of a bubble, including rampant credit growth, corruption and blind faith in the authorities’ ability to prevent a sticky ending. These traits were clearly evident in the 1990s tech bubble.

The other great lost era for equities of the present age also began with the implosion of a spectacular bubble. Japan’s Nikkei 225 index shot up by 469 per cent between the summer of 1982 and the end of 1989. This boom too was fuelled by a cocktail of inappropriately low interest rates, generous – and often irresponsible – lending by banks, and a widespread sense of confidence in the superiority of the Japanese ways of business and finance.

All of these elements were also present in spades during the decade known as the roaring 1920s. Easy credit stoked debt-fuelled speculation in Florida real estate, while Wall Street got carried away with such exciting modern technologies as mass-market versions of radio and the motor car. Excessive confidence in the investment outlook was best encapsulated by the contemporary economist Irving Fisher, who infamously remarked that “stocks have reached what looks like a permanently high plateau.” The Great Crash of 1929 got underway just three days later, wiping out much of the professor’s own fortune.

A big problem with the theory that lost eras result from bubbles bursting is that the 20th century’s other two lost eras in the US were not preceded by manias of the same sort. The 1960s did see something of a boom in the stocks of certain growth companies, in particular, as well as the initial proliferation of mutual funds. But the US stock market as a whole did not experience runaway price growth.

The S&P 500 index went up 84 per cent from the start of the decade to its peak in 1968. And while there was a big influx of novice investors into equities thanks to the arrival of mutual funds, the enthusiasm never came close to that of the late 1990s, where newcomers were so enthusiastic yet uninformed that they sometimes bought into a particular stock mistakenly, merely because its name or ticker was similar to that of a technology stock.

Likewise, even though there was certainly some evidence of exuberance in the stock market around the very start of the 20th century – when stocks rose 163 per cent between August 1896 and September 1906 – this hardly compares to the NASDAQ’s meteoric ascent in the late 1990s, or to the six-fold increase in the US market during the roaring 1920s. The market finally came decisively unstuck when it emerged that the chairman of a leading financial institution of the day had been using the firm’s assets in an attempt to manipulate the copper market.

S...