The Approved Mental Health Professional′s Guide to Mental Health Law

Robert Brown

- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

The Approved Mental Health Professional′s Guide to Mental Health Law

Robert Brown

About This Book

This highly practical book brings together the elements of legislation, Code of Practice, Memorandum, Government Circulars and relevant case law, policy and AMPH regulations that trainees are required to get to grips with to pass the course and practice as a registered Mental Health Professional.

This fully-revised fifth edition is an essential guide for practising AMHPs, or those currently in training. With extensive appendices which cover Mental Health Act Assessments, Practice Directions (first tier tribunal) and the AMHP Regulations for both England and Wales. it also offers checklists, multiple choice questions and exercises to aid practice and learning, and includes:

- Updates to recent legislation, case law and policy

- The impact of the Policing and Crime Act 2017 on patient admissions and the Mental Health Act

- The implications of the 2017-18 Annual Report by the CQC and HIW looking at detained patients

- Anticipated outcomes of the Mental Capacity Act (Amendment) Act 2019

- A new appendix documenting The Mental Health Act 1983 (Places of Safety) Regulations 2017

Frequently asked questions

Information

Chapter 1 Introduction and definitions of mental disorder

- 2(1)(a)(i) mental health legislation, related codes of practice, national and local policy guidance.

- 3(a) a range of models of mental disorder, including the contribution of social, physical and developmental factors;

- 3(b) the social perspective on mental disorder and mental health needs in working with patients, their relatives, carers and other professionals;

- 3(c) the implications of mental disorder for patients, their relatives and carers.

Common law

- The part of English law based on rules developed by the royal courts during the first three centuries after the Norman Conquest (1066) as a system applicable to the whole country, as opposed to local customs . . .

- Rules of law developed by the courts as opposed to those created by statute.

- A general system of law deriving exclusively from court decisions.

The rules which are extrapolated from the practice of the judges in deciding cases. Judges should take a consistent approach to recurring issues and are obliged to follow the decisions of earlier cases, at least when they have been given by the higher courts. Once a matter has been resolved by a judge it therefore sets a precedent which enshrines the legal rule.

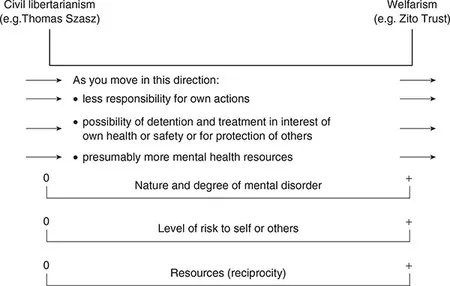

Civil liberties vs welfarism

- mental disorder of a nature or degree to justify this;

- a level of risk to self or others which also justified detention.

Mental health terminology and the law

- 1713/44 Vagrancy Acts allowed detention of ‘Lunaticks or mad persons’.

- 1774 Act for regulating private madhouses.

- 1845 Lunatics Act included ‘Persons of unsound mind’.

- 1886 Idiots Act provided separately for idiots and imbeciles.

- 1890 Lunacy (Consolidation) Act ignored the distinction.

- 1913 Mental Deficiency Act favoured segregation of ‘mental defectives’: idiots were unable to guard themselves against common physical dangers such as fire, water or traffic; imbeciles could guard against physical dangers but were incapable of managing themselves or their affairs; feeble-minded needed care or control for protection of self or others; moral defectives had vicious or criminal propensities (use of this category later included many poor women with unsupported babies).

- 1927 Mental Deficiency Act emphasised care outside institutions. Mental deficiency was defined as ‘a condition of arrested or incomplete development of mind existing before the age of 18 years whether arising from inherent causes or induced by disease or injury’.

- 1930 Mental Treatment Act allowed for voluntary admissions. It enabled patients to enter the county mental hospitals as voluntary patients, as long as they could express volition on admission, it being only necessary for them to sign a form stating they were willing to enter the hospital and would abide by the rules. They could discharge themselves by giving 72 hours’ notice in writing (the opposite approach to the current s5).

- 1946 NHS Act ended distinction between paying and non-paying patients.

- 1948 National Assistance Act made provision for those in need.

- 1959 Mental Health Act. Mental disorder means: ‘mental illness; arrested or incomplete development of mind, psychopathic disorder, and any other disorder or disability of mind’. Further classifications for long-term compulsion were: mental illness, severe subnormality, subnormality, psychopathic disorder, with a kind of treatability test for the last two.

- 1970 LA Social Services Act created Social Services Departments.

- 1983 Mental Health Act. The broad definition was exactly the same as in the 1959 Act. However, the classifications were changed to: mental illness (undefined); severe mental impairment: ‘a state of arrested or incomplete development of mind which includes severe impairment of intelligence and social functioning and is associated with abnormally aggressive or seriously irresponsible conduct on the part of the person concerned’; mental impairment: ‘a state of arrested or incomplete development of mind (not amounting to severe mental impairment) which includes significant impairment of intelligence and social functioning and is associated with abnormally aggressive or seriously irresponsible conduct on the part of the person concerned’; psychopathic disorder: ‘a persistent disorder or disability of mind (whether or not including significant impairment of intelligence) which results in abnormally aggressive or seriously irresponsible conduct on the part of the person concerned’.

- 1984 Police and Criminal Evidence Act (PACE) (plus its Codes of Practice) uses the term ‘mental disorder’ as per the Mental Health Act and the revised PACE Codes use the concept of the mentally vulnerable adult.

- 2002 Draft Mental Health Bill definition: ‘any disability or disorder of mind or brain which results in an impairment or disturbance of mental functioning’.

- 2003 Mental Capacity Bill. Provides for people unable to make a decision ‘because of an impairment of, or a disturbance in the functioning of, the mind or brain’. This then becomes the s2 ‘diagnostic test’ for mental incapacity in the Mental Capacity Act 2005.

- 2004 Revised Draft Mental Health Bill definition of mental disorder was: ‘an impairment of or a disturbance in the functioning of mind or brain resulting from any disability or disorder of the mind or brain’.

- 2005 Parliamentary Scrutiny Committee accepted the above definition but stated: ‘that a broad definition of mental disorder in the draft Bill must be accompanied by explicit and specific exclusions which safeguard against the legislation being used inappropriately as a means of social control’. However, the final version as a result of reforms is . . .

- 2007 ‘Any disorder or disability of the mind’. The word ‘brain’ is removed, which gives at least some potential space between the Mental Health Act definition and that of the test for incapacity in the Mental Capacity Act. However, it is still a very broad definition and the removal of most of the exclusions has potentially broadened it still further. There are no longer any separate classifications of mental disorder, apart from ‘learning disability’ when considering longer-term detention or guardianship. Learning disability is discussed in more detail below.