eBook - ePub

Stress And Its Relationship To Health And Illness

Linas A Bieliauskas

This is a test

Share book

- 142 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Stress And Its Relationship To Health And Illness

Linas A Bieliauskas

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

To discuss the relationship between stress and health status, it is first necessary to define the term "stress." This is not a mundane issue, because the term "stress" is popularly used to refer to a wide range of physiological changes, psychological states, and environmental pressures in the health/illness literature. Stress was first described as a biological syndrome by Selye (1936, p. 32): Experiments on rats show that if the organism is severely damaged by acute non-specific nocuous agents such as exposure to cold, surgical injury, production of spinal shock... a typical syndrome appears, the symptoms of which are independent of the nature of the damaging agent... and represent rather a response to damage as such.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Stress And Its Relationship To Health And Illness an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Stress And Its Relationship To Health And Illness by Linas A Bieliauskas in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Scienze sociali & Sociologia. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction to the Concept of Stress

Background and Definition of Stress

To discuss the relationship between stress and health status, it is first necessary to define the term "stress." This is not a mundane issue, because the term "stress" is popularly used to refer to a wide range of physiological changes, psychological states, and environmental pressures in the health/illness literature. Stress was first described as a biological syndrome by Selye (1936, p. 32):

Experiments on rats show that if the organism is severely damaged by acute non-specific nocuous agents such as exposure to cold, surgical injury, production of spinal shock . . . a typical syndrome appears, the symptoms of which are independent of the nature of the damaging agent. . . and represent rather a response to damage as such.

This syndrome is the manifestation of a state called "stress" that included all the specific changes induced within the biological system of an organism. That which produces this state of stress is called the "stressor." The primary emphasis of Selye's observation was that stress shows itself as a measurable organismic reaction although it may be "unspecifically induced"; that is, it is a general reaction that occurs in response to any number of 1 different stimuli (Selye, 1956). The biological reaction to which Selye referred was characterized by a general increase in the production of certain hormones from the pituitary and adrenal glands that augmented or ameliorated the mobilization of bodily defenses against different stressors (Selye, 1971). We will discuss the biological characteristics of this reaction more specifically in the next chapter.

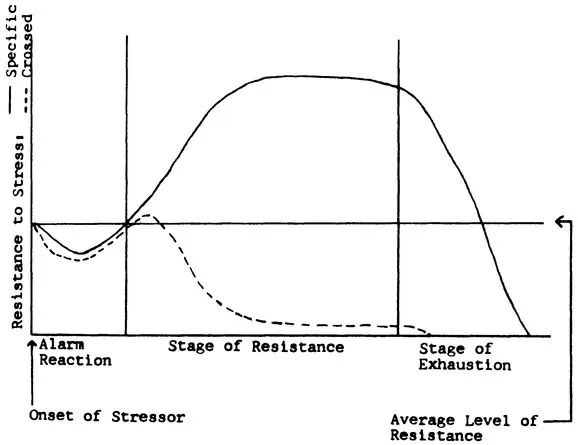

FIGURE 1. The General Adaptation Syndrome. (After Selye, 1946. Reproduced by permission of The Endocrine Society.)

Selye saw the stress reaction as an adaptive syndrome of the organism in response to external stressors. The form this syndrome takes is known as the General Adaptation Syndrome (GAS) and is depicted in Figure 1. The GAS consists of three phases. Upon confrontation with a stressor, the organism enters the first phase, the alarm reaction, in which overall resistance to a stressor initially decreases, although bodily defenses-for example, inflammation-are mobilized. If the stressor is very intense at this point or if many additional stressors are present, resistance diminishes to zero and the organism ceases to function. During the second phase, the stage of resistance, the organism adapts to the presence of the stressor and maintains itself. The stressor can even increase in magnitude during this stage without causing obvious harm. Bodily defenses are effective, and the organism either maintains these defenses or tolerates the presence of the stressor without extended use of direct defenses. For example, a fever is a direct defensive inflammatory response to a viral pathogen. However, if maintained over extended periods, it might itself harm the organism. Therefore, a pathogen might be tolerated by the body without a direct defensive reaction, as in the case of viral infections that continue over time without any evidence of fever. In such cases, the organism is resisting the pathogen passively by tolerating it rather than actively by fighting it. Nevertheless, whether the organism resists a stressor actively or passively, its capacity to do so is finite; the presence of a stressor over an extended period will deplete the organism's resistance capacity and eventually lead to breakdown or death during the third phase, the stage of exhaustion. Of course, the GAS is a conceptual description of the typical reaction to a stressor and is not intended as a specific depiction of exact organismic symptoms and biological changes.

While the GAS is intended to buttress an organism's resistance to a particular stressor, it also necessarily alters the physiological balance that prevailed before the stressor appeared. This bodily change may have direct deleterious consequences for the organism if the GAS is maintained over extended periods. Selye (1956) described these negative consequences as "diseases of adaptation," although he admits the term is less than precise. In addition, the GAS may either increase or decrease potential resistance to another stressor, depending on the circumstances (Selye, 1946).

As mentioned above, an organism can respond to the presence of a stressor by direct defense or by tolerance. This dual action of the stress response is theorized to result in crossed resistance or crossed sensitization to additional stressors (Selye, 1952). Initially, exposure to a systemic stressor increases resistance to that stressor and provides an already mobilized capacity to cope with other stressors of a similar nature (crossed resistance). However, this exposure to a systemic stressor may also lead to the development of a tolerance to stressors and thus a diminished capacity to deal with additional stressors of a different nature (crossed sensitization). For example, if a tolerance is developed for the presence of a particular viral pathogen, the organism might not be able to combat an ensuing invasion of a bacterial pathogen (see Figure 1).

This traditional conceptualization of stress, then, views it as a specific biological syndrome that is a response to nonspecific damaging agents (stressors). The response has a particular timeframe (the GAS), and its activation by one stressor may have implications for the organism's capacity to resist other stressors (crossed resistance or crossed sensitization). This view of stress is still widely accepted, but there is evidence that it is oversimplified.

The idea that stress is a purely biological response has been challenged by Mason (1971), who asserted that a single biological response to a wide variety of stimuli is difficult to explain on a physiological basis. In a series of experiments, he demonstrated that the general stress response was dependent on psychological parameters surrounding the stressors. By controlling the degree of discomfort, the pleasantness, or sudden versus gradual appearance of stressors, Mason was able to show that such factors could account for the presence or absence of the biological stress response even if the actual stressors-say, workload or lack of nutrition-remained unchanged. Thus, Mason felt that "the stress concept should not be regarded primarily as a physiological concept but rather as a behavioral one" (1971, p. 331). Any response an organism makes to stressors is likely mediated first at the behavioral level and then may have a secondary physiological impact.

A second major challenge to the concept of GAS has focused on its basic tenets of nonspecificity of induction and universal response. The initial arguments for psychosomatic medicine (the influence of psychological factors on health and illness) were based on a specificity approach-different types of illness have different psychological precursors (Alexander and Selesnick, 1966). From this viewpoint, a disease like hypertension is specifically related to difficulty with release of anger, while an illness like asthma is related to exaggerated dependency needs. Although this line of reasoning is generally not considered to have been fruitful (Oken et al., 1962), recent research has demonstrated that there are different patterns of hormonal response to different physical stressors (Mason et al., 1976) and that different kinds of stressing situations may lead to different autonomic responses in a single organism (Lacey, 1967; Shapiro, Tursky, and Schwartz, 1970). Research has also shown that individuals who have historically experienced difficulties with one organ system tend to respond to stressors with signs and symptoms within that system. Wolf and Goodell (1968), for example, found that patients with vascular headache, cardiovascular problems, and duodenal ulcers showed a stress related hyperactivity in those particular organs. Finally, social situations, emotions, and coping abilities have all been shown to affect different aspects of the stress response.

In general, current research suggests that the stress response is not a simple biological response to nonspecific stressors but rather a complex, interrelated process including the occurrence of a stressor, how it is seen psychologically by the organism, under what circumstances the stressor occurs, how the organism characteristically reacts, and what the resources are that the organism has available for dealing with the stressor. The concept of a general stress reaction may be viable, but only if we assume that it represents the sum of a great many psychological and physiological factors rather than a specific all-or-none response to the occurrence of a stressing event.

This view of stress as a primarily psychological and only secondarily physiological concept has certain implications. First, as already mentioned, the context of a stressor is just as important as the stressor itself in determining whether an organism will respond to the event with stress. Second, psychological characteristics of the organism will also determine the presence or absence and nature of the stress response. Third, while it is true that psychological characteristics of the organism influence the stress response, stressors can themselves be psychological as well as physical. Mason (1968) has pointed out overwhelming evidence of psychological influences on stress-related physiological changes. Only with these factors firmly in mind, then, can we accept the GAS as a basic model for the general nature of the stress response.

Stress and Illness

Current interest in the concept of stress as it relates to health and illness undoubtedly began with anecdotal reports of illnesses that seemed to occur during periods of major change in people's lives. For example, it is well known that the recently widowed and divorced have higher mortality rates than all other segments of the population (Carter and Glick, 1970). Adolph Meyer (Lief, 1948) was one of the first to recognize and measure the impact of significant daily life occurrences on subsequent illness. He developed a "life chart" that organized medical, psychological, and sociological data for each individual, and from those charts, patterns began to emerge. Since that time, many others have investigated the relationship between daily life stressors and illness. The essential point of this approach is that life events are seen as nonphysical stressors and that the data suggest there is a positive relationship between those events and the subsequent occurrence of illness. As might be expected, this relationship is quite complex and its magnitude appears to be highly dependent on a variety of situational, individual, and constitutional differences.

A simplifed schema of the relationship we have been discussing may be depicted as follows: This schema outlines a stress pattern that can potentially identify risk factors for the incidence or exacerbation of illness and provide clues about the most effective way to change the situation (by removing the stressor, by lowering the stress, or by treating the illness directly). For example, let us suppose an executive is experiencing a continuing stressor such as constant job pressure. At this point we could say that he is demonstrating a stress response that, according to the model of the GAS, would be in the stage of resistance. Let us suppose that now an additional stressor occurs, such as exposure to a viral pathogen. Because our executive is already resisting one stressor, he may well experience sensitization to the second stressor and succumb to illness more readily than if he were not reacting to a stressor already. Of course, even without an added stressor our executive might fall ill simply from the effects of continued pressure from the original stressor. His means of tolerating that stress may well impair his day-to-day functioning over time and lead to a peptic ulcer, for example.

The foregoing is necessarily an oversimplified version of current stress-illness research, but it does provide us with a general introduction to how stress is conceptualized and how it interacts with illness. Stress is a response, both psychological and biological, that is related to illness according to certain patterns, as predicted by the GAS or other theories we will discuss in the following chapters. Let us now begin to examine the complexity of this relationship from a physiological point of view.

2

Hormonal Responses to Stress

The Complexity of Hormonal Stress Responses

Selye (1952) initially described the biological stress response as follows: The presence of a stressor (through imperfectly understood mechanisms) acts upon the anterior pituitary and stimulates the secretion of somatotropic (STH) and adrenocorticotropic (ACTH) hormones. Although STH acts to stimulate the growth of the body in general, and the growth of thymicolymphatic tissue in particular, it also stimulates the growth of connective tissue to repair physical damage and raises the inflammation potential of the organism to help prevent infiltration by a foreign pathogen. The action of STH can be classified as primarily prophlogistic, that is, it augments inflammation and combats the pathogen.

ACTH, on the other hand, stimulates the adrenal cortex to produce two classes of hormones, the mineralocorticoids and the glucocorticoids (Selye, 1952). The mineralocorticoids are classified as prophlogistic corticoids (PC) because they mimic the effect of STH in response to a stressor: they increase inflammation and promote connective tissue proliferation. However, as we noted in Chapter 1, extended prophlogistic reaction -such as a high fever (inflammation reaction)-may threaten the life of the organism. Therefore, if PC action cannot adequately control a stressor, that action must be terminated lest serious consequences result. According to Selye (1956), overextended prophlogistic activity may cause nephrosclerosis, hypertension, and allergic reactions.

The glucocorticoids are classified as antiphlogistic corticoids (AC) in that they are anti-inflammatory and thus inhibit PC aggrandizement. AC action is initiated as PC-affected tissue becomes increasingly sensitive to the ACs. Selye (1950) called this antiphlogistic response "adaptation." Because ACTH secretion is necessary for AC production, ACTH is generally classified as antiphlogistic. However, continued AC action may also harm the organism as a whole by diminishing specific resistance to microbial pathogens (suppressing the immune response) and delaying wound healing. Other consequences of over-extended antiphlogistic action would be necrosis, thymolysis, adrenal hypertrophy, catabolism, ulcers, and possible precipitation of psychosis (Selye, 1956). In reference to the GAS, PC action would predominate during the alarm reaction and AC action would prevail during the stage of resistance. A graphic representation of Selye's understanding of AC and PC action can be seen in Figure 2. However, in Figure 2, you can see that the stress response is not so simple: a feedback loop serves to regulate ACTH production in the pituitary.

Further research showed that even adrenalectomized animals could demonstrate patterns of resistance to stressors (Selye, 1971), that multiple organ systems were involved in corticoid production, and that auto...