![]()

1

Philosophical Background: Universal Ideas

Philosophy has a bad reputation among scientists, who regard it as being either irrelevant to science or opposed to it. In particular, political philosophy has been accused of being opportunistic rather than principled, as well as imprecise and only loosely related to the bulk of philosophy. Peter Laslett (1967: 370) noted that the said opportunism “has led to a raggedness, even an incoherence, in works devoted to it and to an emphasis on intuitive arguments which compares unfavorably with the content of other philosophical literature.” Many years later the same scholar added a complaint: Political philosophers overemphasize the history of political thought at the expense of contemporary challenges (Laslett in Skinner 2002: 2).

However, nobody can avoid philosophy when discussing anything other than everyday events. If in doubt, try do politology without using the notions of thing and process, reality and appearance, cause and chance, person and society, behavior and norm, assumption and deduction, datum and theory, indicator and test, science and ideology—and then some. One can. and usually does, use them without pausing to examine them. However, tacit philosophy is sloppy and uncritical. To avoid these two flaws we must analyze and systematize universal concepts. We must build precise theories around them. This is a task for good philosophy.

The present chapter sketches what I hope to be a coherent philosophical system, and it offers suggestions on how to sharpen some key philosophical concepts relevant to the study of politics. Some of these concepts occur, albeit implicitly for the most part, in the works of the much-maligned Niccolò Machiavelli (1940). Machiavelli founded not only modern political technology, or the art of mass persuasion, but also modern political theory. Thus, he inspired not only Hitler, Stalin, and terror peddlers, but also all the serious political theorists of the modern era, from Hobbes and Locke to our day.

I submit that Machiavelli’s scientific success was largely due to his modern philosophical outlook, tacit and sketchy as it was. In fact, his ontology was both secular (unlike that of his Christian predecessors) and dynamicist (unlike Plato’s and Husserl’s). Machiavelli viewed the polity as a concrete whole in perpetual flux whose individual components were moved primarily by worldly interests. He was confident that, by studying the mechanisms of political change, he would be able to understand and control them for the benefit of the sovereign.

Contrary to Plato and Aristotle, but foreshadowing Galileo, Machia velli regarded change as a mark of perfection, not imperfection. He was also the first to state that politics is not just a game played by princes (rulers), but also a process involving masses of individuals who attempt to foresee the consequences of their actions. Machiavelli was also an epistemological realist. He believed in the independent existence of the external world, as well as in the possibility of getting to know it. In short, by and large, Machiavelli may be regarded as a materialist of sorts, as well as a realist, a rationalist, and an utilitarian. True, he also believed in magic, but this played no role in his theory, just as Newton’s God did not occur in his equations of motion.

One may tackle a circumscribed political problem, such as whether proportional representation is fair and workable, within a single branch of a discipline. But the big issues of any kind, such as poverty, can only be tackled with the help of several disciplines and within a broad philosophical framework. This is so because political action occurs in the real world, is planned in the light of some body of knowledge and some moral code, and is likely to benefit some people while harming others.

For example, the design and implementation of any promising (or threatening) public works, health, or education program presupposes a secular worldview, a realistic epistemology, an action theory mindful of interests, and a consequentialist (though not necessarily utilitarian) moral philosophy. In short, I submit that philosophy contributes to fashioning the polity via political theory and political action as suggested by the following flow diagram:

Philosophy → Political theory → Policy → Political debate →Political decision → Planning → Execution → Evaluation → Eventual policy or plan redesign

The naïve materialist might object that this view is idealistic, because it presents certain facts as consequences of ideas. But as it so happens that deliberate action, by contrast to knee-jerk reaction, is carried out in the light of ideas intertwined with moral sentiments. (Any decision to take action is preceded by deliberations guided or distorted by desires rooted in interests, as well as constrained or fuelled by morals.) Admitting this is no concession to philosophical idealism, provided ideas are regarded as brain processes, not as existing by themselves. So, the entire process we have just sketched occurs in the real world inhabited by political agents.

The relevance of philosophy to political science research is obvious from the approach to the discipline chosen by the authors in the four more influential American and British journals in the field during the 1997-2002 period (Marsh and Savigny 2004). For example, 56% of the contributors to the American Journal of Political Science opted for “behaviouralism,” or respect for empirical data, whereas rational-choice theory—characterized by its apriorism—was the choice of only 15% of the authors. The corresponding data for the British Journal of Political Science were 63% and 9% respectively.

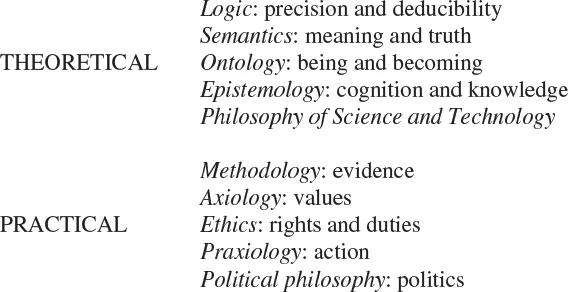

In this chapter I will sketch the philosophical disciplines involved in political philosophy. In my view authentic philosophy consists of the following branches:

All of the key ideas in these philosophical disciplines will play a role in each chapter of this book. However, the reader should remember that, unlike mathematics or chemistry, philosophy is plural, in the sense that every philosophical view belongs to some school or other—rationalist or irrationalist, idealist or materialist, individualist or systemist, and so on.

I have chosen my own philosophy, which I have discussed in detail in previous works, particularly in the eight volumes of my Treatise on Basic Philosophy (1974-89), as well as in three books on the philosophy of social science (Bunge 1996a, 1998a, 1999a), in my latest books on ontology and epistemology (Bunge 2003a, 2006a), and in an anthology on my scientific realism (Mahner 2001). But I claim that, though biased as all philosophies, mine is both precise and evidence-based. The evidence I offer for or against philosophical hypotheses comes from science and technology. For instance, if I regard every thing as changeable and as either a system or a component of one, it is because so does every science proper. In other words, my philosophy is unabashedly scientistic, that is, science-centered.

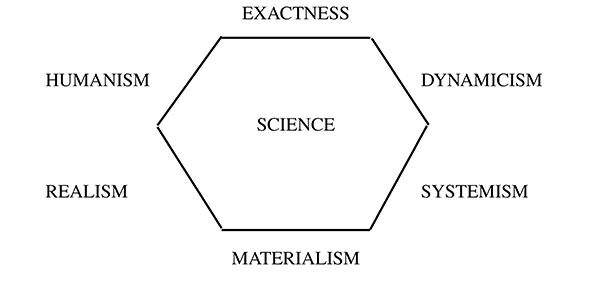

This philosophy may be summarized as a hexagon centered in science, and the sides of which are my own versions of emergentist materialism (as opposed to both idealism and radical reductionism); systemism (as the alternative to both individualism, or atomism, and holism, or structuralism); dynamicism, or the thesis that everything in the real world is changeable; scientific realism (as opposed to naïve realism, subjectivism and relativism); humanism (as opposed to supernaturalism and egoism); and exactness, as opposed to imprecision and obscurity. I will attempt to show the relevance of each of these philosophical views to both political science and political philosophy. I will also argue that a philosophy without logic and semantics is mushy; without ontology, spineless; without epistemology, headless; and without ethics, clawless.

1. Logic: Conceptual Rationality

Let us glimpse at political reasoning. What thinks and feels about political issues and what to do about them is a brain. And brains can work either rationally and realistically or not. These two conditions, rationality and realism, are quite distinct. One may argue rationally about ghosts, the way rational-choice theorists do when using undefined utilities and probabilities. Or one may stick to reality yet think irrationally about it, the way postmoderns have been doing—as when Derrida stated that “[w]hat is proper to a culture is to not be identical to itself” (in Coles 2002: 311).

To argue correctly about anything, whether real or imaginary, one must stick to the rules of rational argument. These rules are studied by formal (or mathematical) logic, the most abstract and therefore the most general and portable of all sciences. We need logic not to generate ideas but to check them for cogency and to spot dangerous nonsense such as “authoritarian socialism,” “democratic centralism” (the internal mechanism of communist parties), “vertical labor union,” and “war on terror.”

Logic deals with concepts, such as the predicate “is democratic,” as well as with propositions or statements, such as “Only democracy safeguards human rights.” Concepts are designated by symbols, such as words, whereas propositions are designated by sentences in some language. Since there are several thousands of languages, one and the same concept can be designated by thousands of symbols; propositions are parallel. Only propositions, or statements, can be true or false to some degree. For instance, “liberty” is neither true nor false, whereas “Liberty must be either conquered or defended” is arguably true. However, logic is concerned with precision and formal validity, in particular logical consequence, not truth. Indeed, the principles and rules of logic hold regardless of content and truth-value.

Paradoxically, the logical assumptions and their consequences are empty. They state nothing in particular, which is why they are called tautologies. Yet, some politicians love tautologies, either out of ignorance or because they do not commit us to anything. For example, President George W. Bush once proclaimed: “Those who enter the country illegally violate the law.” He also invented the slogan “War on terror,” which is a contradiction in disguise, since war is the worst terror.

Logic does not handle sentences that fail to represent propositions, such as questions, requests, regrets, imperatives, and counterfactuals. But of course questions, requests, regrets, and imperatives, though devoid of truth-values, are indispensable. The same cannot be said of contrary to fact statements, even though they are rampant in political rhetoric. Remember what the same politician cited above said: “If we had not invaded Iraq, this would now be a terrorist nursery.” Contrary to the widespread belief that the person in question is fond of uttering lies, that particular sentence is neither true nor false. However, it signifies roughly the same as the declarative sentence “We attacked Iraq because it was bound to become a terrorist nursery.” Contrary to the corresponding counterfactual sentence, this one does express a proposition, though one that is neither supported nor undermined by any evidence, whence it cannot be assigned a truth-value. We only know that, five years after being invaded, Iraq has become a breeding ground of “terrorists,” also called “insurgents,” or “patriots” by some. The moral is that counterfactuals should be handled with care, particularly in matters of life and death.

The most important of all logical rules are the law of non-contradiction and the inference rule called modus ponens. The former states that the joint assertion of a proposition and its denial is false: A and not-A is false regardless of the content of A. And the modus ponens is the rule: From A and “If A, then B,” deduce B.

Paradoxically, contradictions are excessively fertile, as they entail any propositions whatsoever. By contrast, the conjunction of “If A, then B” with B, entails nothing. To claim that it does is to incur a classical fallacy. For instance, from the generalization “The representatives who keep their word are reelected,” and the datum “He was reelected,” it does not follow that he kept his word. In fact, every body of representatives is full of people who have repeatedly broken their promises.

Logic is then the torchlight that helps us spot wrong arguments. But how do we argue for the logical rules? We seldom do, because any valid argument about anything involves the rules of debate. Drop the law of non-contradiction, and you’ll incur the cheapest of all falsities: contradiction, which amounts to losing the debate. And if one drops the modus ponens, one is unable to conclude anything from any set of premises, not even to check whether they beget contradiction. Thus logic, the least of constraints upon rational discourse besides clarity, is not only essential to all sound discourse: it also keeps us from falling into either nothingness or everything.

This is why Heidegger, Jaspers, Gadamer, Arendt, Derrida, Irigaray, Vattimo, and the other so-called postmoderns rejected logic: Irrationality allowed them to put words together without worrying about sense, let alone coherence and evidence (see Edwards 2004). And of course irrationalism helps dictators, for it disarms analysis and criticism, and replaces universal theories with tribal beliefs. This is why fascism, in all of its versions, sought “to fight the very ideas of objective truth and universal reason” (Kolnai 1938: 59).

It is nearly impossible to argue with people who excel in esoteric gibberish and ignore the rules of rational debate. For instance, how can anyone argue in favor or against Heidegger’s (1954: 76) esoteric assertion that Being “is It itself”? The postmodernist Gianni Vattimo calls this kind of “thinking,” which he commends, “weak thinking.” I think it deserves being called pseudothinking. Esotericism, commended by Leo Strauss, serves to conceal vacuity or malice. However, let us go back to genuine reasoning—clear and cogent argument.

Logic is the most general (and therefore also the most abstract) of all sciences, because it is topic-neutral, hence portable from one field to the next. This is why there can be no political logic any more than chemical logic. However, logic leaves practical reasoning out: it does not cover inference patterns such as this:

This is an instance of practical reasoning. It relates facts rather than statements, and it involves a value judgments and an imperative. We shall return to practical reasoning in Chapter 8, Section 2. For the time being, suffice it to note that honest political discourse contains practical as well as logical arguments.

Rational debate is not privative of academic life: it is also a feature of democracy. Indeed, political strife and the administration of the commonwealth involve rational deliberations about means and ends, even for the invention and execution of dumbing political campaigns, such as the Nazi appeal to “blood and soil.” But of course rational debate, though necessary, is never sufficient. Only naïve rationalists could believe that political conflicts can be resolved exclusively by rational discussion: rationality should guide political contest, if only to minimize damage, but it cannot replace struggle. Regrettably, interests backed by force can overpower the most cogent arguments: God favors the good guys when they outnumber the bad.

Rationality is so much taken for granted in all walks of life, that we find irrational behavior unsettling, and that some military strategists have recommended simulating irrationality to confuse and scare the enemy. Schelling (1960) called this policy the “rationality of irrationality”; and President Nixon, Professor Kissinger’s star pupil, called it the “madman theory.” In playing with rationality, those people, along with their Soviet counterparts, were playing with the survival of the human species.

Let us deal briefly with the concept of a theory. Some political scientists equate political theory with normative politology (or political philosophy, or social engineering). This usage is idiosyncratic and misleading, for in all the mature science...