Media Theory for A Level

The Essential Revision Guide

Mark Dixon

- 230 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Media Theory for A Level

The Essential Revision Guide

Mark Dixon

About This Book

Media Theory for A Level provides a comprehensive introduction to the 19 academic theories required for A Level Media study. From Roland Barthes to Clay Shirky, from structuralism to civilisationism, this revision book explains the core academic concepts students need to master to succeed in their exams. Each chapter includes:

• Comprehensive explanations of the academic ideas and theories specified for GCE Media study.

• Practical tasks designed to help students apply theoretical concepts to unseen texts and close study products/set texts.

• Exemplar applications of theories to set texts and close study products for all media specifications (AQA, Eduqas, OCR and WJEC).

• Challenge activities designed to help students secure premium grades.

• Glossaries to explain specialist academic terminology.

• Revision summaries and exam preparation activities for all named theorists.

• Essential knowledge reference tables.

Media Theory for A Level is also accompanied by the essentialmediatheory.com website that contains a wide range of supporting resources. Accompanying online material includes:

• Revision flashcards and worksheets.

• A comprehensive bank of exemplar applications that apply academic theory to current set texts and close study products for all media specifications.

• Classroom ready worksheets that teachers can use alongside the book to help students master essential media theory.

• Help sheets that focus on the application of academic theory to unseen text components of A Level exams.

Frequently asked questions

Information

1 Semiotics

Roland Barthes

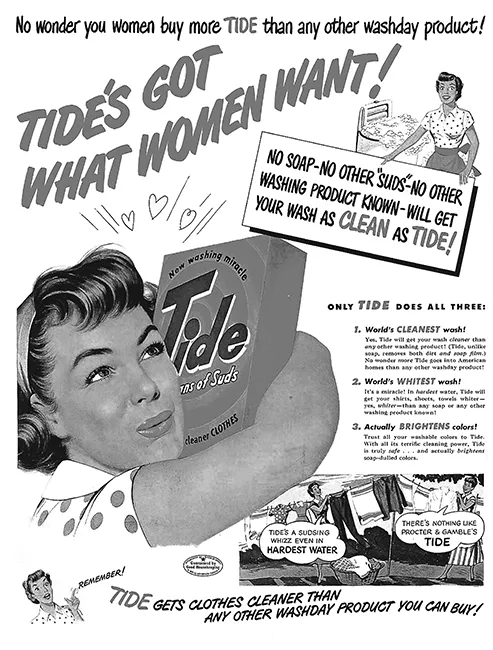

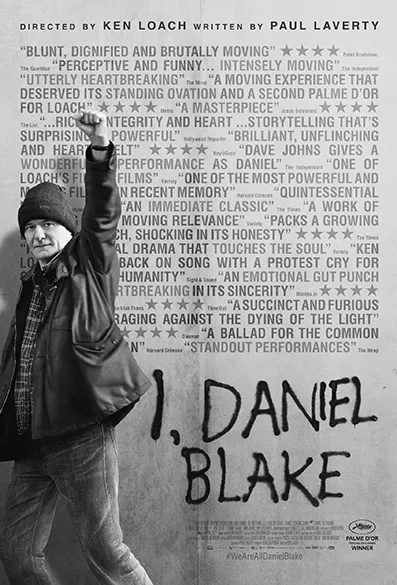

Concept 1: denotation and connotation

Denotation/connotation

| Image makers use a range of strategies to infer meaning within imagery – look out for the following when analysing the meaning making effects of your set texts. | |

| Image features | Look out for |

| Pose Subject positioning, stance or body language | Fourth wall breaks: where the photographic subject meets the gaze of the audience. This can create a confrontational, aggressive or invitational feel. Off-screen gaze: upward gazes can suggest spirituality; right-frame gazes can suggest adventure or optimism; left-frame gazes can suggest regret or nostalgia. Body language control: might be open or closed, passive or active, strong or weak. Subject positioning: the way that group shots are arranged is usually significant with power conferred on those characters that occupy dominant positions. Proxemics: refers to the distance between subjects – the closer the characters are the closer their relationship. Left-to-right/right-to-left movement: characters who travel from screen left to screen right create positive connotations – they are adventurers and we might feel hopeful about their prospects; right-to-left movements can suggest failure or an impending confrontation. |

| Mise en scène Props, costume and setting | Symbolic props: props are rarely accidental – their use and placement generally infer symbolic meanings. Pathetic fallacy: settings and scenery often serve further symbolic functions – weather, for example, infers the tone of characters’ thoughts. Costume symbolism: character stereotypes are constructed through costuming, helping us to decipher a character’s narrative function. |

| Lighting connotations | High-key lighting: removes shadows from a scene, often producing a much lighter, more upbeat feel. Low-key lighting: emphasises shadows and constructs a much more serious set of connotations. Chiaroscuro lighting: high contrast lighting usually created through the use of light beams penetrating pitch darkness and connotes hopelessness or mystery. Ambient lighting: infers realism. |

| Compositional effects Shot distance, positioning of subjects within the frame | Long shots: imply that a subject is dominated by their environment. Close ups: intensify character emotion or suggest impending drama. Left/right compositions: traditionally the left side of the screen is reserved for characters with whom the audience is meant to empathise and vice versa. Open/closed frames: open framing suggests freedom, while enclosing a character within a closed frame can suggest entrapment. Tilt and eye line: tilt-ups and high eyelines convey power, while tilt-downs and low eyelines connote powerlessness and vulnerability. |

| Post-production effects | Colour control: colours are often exaggerated for specific connotative effect – red: anger; white: innocence; blue: sadness and so on. High saturation: colour levels are increased creating a cheerier, upbeat feel. Desaturation: taking colour out of an image generates a serious or sombre tone. |

Text and image