![]()

Central questions and basic assumptions | I |

There are some aspects of human beings that appear so natural and so self-evident that it seems almost trivial to mention them or to think about them, and, at first glance, one might not expect psychologists to investigate these phenomena. For instance, humans have a concept of time: We differentiate what happens now from what happened yesterday and what will happen tomorrow. Similarly, we structure our world in space and we “see” that one object is further away from us than another one. Moreover, humans are disposed to search for the causes of events: Individuals do not merely register events, but they attempt to explain why they happened. The scientific analysis of the “obvious” has, however, often resulted in very fruitful research programmes such as the psychology of the understanding of time (Fraisse, 1985) and of the perception of depth (see Eimer, 1994). Attribution research, which is concerned with the particularity of human beings to perceive the causes of events and to make causal inferences, is one of these fruitful research fields as well.

![]()

The topics of attribution research | 1 |

As the search for the causes of events is an “everyday” or “commonsense” activity, we all can give numerous examples for having made causal explanations or attributions (see Kelley, 1992). Why did I succeed at this exam? Why did I get such a nice compliment from my friend? Why does the baby cry? And why did I get the present? The answers to such “why-questions” often have far-reaching implications for the most important aspects of our life: Explaining a successful exam through high ability might motivate us to further study this topic, whereas the insight that success was due to the ease of the task might lead to decreased interest in the area. Attributing a friend’s compliment to her honest approval might be a source of great joy, whereas tracing it back to ingratiation might give rise to disappointment or to anger. And if you believe the baby cries because she is hungry you will feed her, whereas tracing back the crying to fatigue will lead you to try to calm her down.

Causal explanations also constitute an important aspect of work conducted within the legal system and other institutions of society (see Hart & Honoré, 1959). The police are expected to find the person responsible for the death of the victim; the judge has to decide what the victim’s exact cause of death might have been. Murder or manslaughter? The task force of the aviation administration searches for the cause(s) of the plane crash; and, following an election, the political party seeks to determine whether the defeat or victory was due to the election campaign or to the personalities of specific candidates.

Attribution theory is concerned with such why-questions. It is a theory (or better, a group of theories) about how common sense operates or, in other words, about how the “man (or woman) in the street” explains events and the psychological consequences of such explanations (see Kelley, 1992). Attribution theories are (scientific) theories about naive theories, that is, they are metatheories; attribution theories are not (or only indirectly) concerned with the actual causes of behaviour but they focus on the perceived causes of behaviour. To illustrate: The research question as to how intelligence influences exam performance would not fall in the realm of attribution theory. However, a classical question of attribution research is under what circumstances individuals (subjectively) believe that their exam performance was caused by intelligence (or lack of).

Attribution theory is primarily concerned with naive psychological theories, that is, how the “man on the street” explains his own or other individuals’ behaviours and behavioural outcomes; therefore, attribution theory makes “naive psychology” its topic. Although attribution researchers have occasionally asked how individuals explain events out of the domain of physics (e.g., acceleration or movements of objects) or answers to questions like “why does my car not start?” (i.e., a concern of “naive mechanics”), the central focus has been on the analysis of naive psychological explanations (e.g., “why did I fail this task?”). Hence, attribution research is particularly concerned with the “naive psychologist” and less so with the “naive physicist”. However, naive scientific (e.g., physics) theories are becoming an increasingly popular field in developmental psychology (see, e.g., Carey & Gelman, 1991; Wilkening & Lamsfuß, 1993).

As attribution theory is concerned with phenomena from “everyday life”, this approach has also been labelled “the psychology of common sense” or the “psychology of the man on the street”. The fact that attribution theories address everyday common-sense phenomena implies that attribution research is not concerned with phenomena of questionable ecological validity that might only occur in rare laboratory situations or in selected clinical groups. (As just mentioned, we all make attributions quite frequently.) In contrast, attribution theory is concerned with the processes that make our everyday circumstances understandable, predictable, and controllable, and, hence, the insights of attribution research are applicable to a wide area of domains such as achievement, love, health, friendship, and pathology.

Scientific psychology is concerned with the description and explanation of behaviour and experience. If humans are conceived of as “naive scientists” it follows that the scientific study of “common sense psychology” (attribution theory) must focus on how naive individuals describe and explain behaviours and experiences. With regard to the description of naive psychology, it follows that it must, at least in part, include observations that we all have already made, and it (the scientific description of common sense) should therefore include “unsurprising” facts (see Kelley, 1992). Therefore, attribution theory has occasionally been referred to as the “psychology of the obvious”. In fact, attribution research starts with descriptions of facts that are obvious and that we all know (e.g., people explain their performances through effort and ability). However, we will see that attribution research has also revealed quite a few surprising and contra-intuitive observations about common sense. In this respect, attribution theory and research has similarities with physics, which has its basis in phenomena with which we all are familiar (e.g., gravitation) but which also extends to phenomena that we can hardly believe (e.g., relativity).

Science’s even more important task—aside from description—is explanation. Consequently, attribution theory not only describes common sense, but also attempts to give a scientific theory as to how common sense “works” (e.g., under what circumstances do people explain their performances with ability and when with effort?). We will see that such explanations of how common sense operates (i.e., the “heart” of attribution theories) are not part of common sense itself and not part of the knowledge of individuals that are unaware of scientific psychology.

As already mentioned, searching for the causes of events is not only an undertaking of everyday life, but also one of the most important features of science. Scientists professionally search for the causes of, for instance, earthquakes, depression, cancer, and the destruction of the ozone layer. Attribution research has alluded to this similarity between laypersons and scientists and has often assumed that in their everyday attempts to find the causes of events, humans use methods or “tools” that are similar to those used by scientists (see Gigerenzer, 1991). Hence, attribution theorists have used the metaphor of the scientist while investigating naive explanations, and they have referred to the “man in the street” (i.e., us all) as “naive scientist” or naive psychologist who is motivated to find accurate answers to why-questions.

Stated somewhat differently, attribution theory and research first informs you about how “the man on the street”, the naive psychologist, explains events. As you and I and everybody else are “naive psychologists”, you will already know some of the discoveries of attribution research. However, some of what you already knew about common sense will be systematised more precisely by attribution theory. In addition, you will gain some new and surprising insights about some aspects of common sense. But, most importantly, you will be confronted with a set of scientific theories that explain how common sense works. So if you are interested to find out, for instance, why some individuals explain their failing a task with low ability, whereas others tend to believe that failure was due to bad circumstances, and if you want to find out what emotions and behaviours such explanations elicit and how such causal explanations can be influenced or changed, you will find the answers to these questions in the present book.

The history and present status of attribution research

The topic of causality and the analysis of causal explanations have a long tradition in philosophy and in psychology, starting about two thousand years ago with Aristotle’s differentiation of various types or classes of causes. About two hundred years ago, the foundations for the current psychological models of perceived causality had been laid by the philosophers Hume (1740/1938), Kant (1781/1982), and Mill (1840/1974) (see Eimer, 1987; Einhorn & Hogarth, 1986; White, 1990). Hume postulated that there are some basic prerequisites that have to be met before we consider one event to be the cause of another. Consider, for instance, that lightning strikes a barn, and the barn starts to burn. In this example, the lightning will be considered by most observers to be the cause of the burning of the barn, because (1) the lightning temporally precedes the burning of the barn (i.e., there is temporal contiguity between the cause and the effect), (2) the lightning appears to “touch” the barn (i.e., there is spatial contiguity between the cause and the effect). Most characteristic, however, of Hume’s position is (3) that the cause and the effect (i.e., the lightning and the burning of the barn) must co-occur repeatedly before we consider the former as a cause for the latter. He asserted that causality is not an inherent property of sensory events that is directly “perceivable”. Causality, according to Hume, can only be inferred on the basis of prior knowledge (repeated observations).

Hume’s ideas were later taken up, elaborated, and specified by Mill (1840/1974). Mill pointed out that we also tend to perceive the non-existence of an event as a cause. For instance, the insurance company might argue that the absence of the lightning conductor had caused the barn to catch fire during the thunderstorm. In this context, Mill introduced several methods that scientists should adopt to determine the causal relations of events; among them is the Method of Difference that was later taken up by attribution theorists (Heider, 1958; Kelley, 1967; see Part II), whose models then dominated attribution theory’s analyses of perceived causality. Mill states: “If an instance, in which the phenomenon under investigation occurs, and an instance in which it does not occur, have every circumstance in common save one, that one occurring only in the former, the circumstance in which alone the two instances differ is the effect or the cause, or an indispensable part of the phenomenon” (p. 452).

In contrast to the position of Hume and Mill, however, other philosophers have argued that causality is an immanent category of the human mind (see, Kant, 1781/1982) or that causality can in fact be directly “perceived” (Ducasse, 1924, 1926; see, for a summary, Eimer, 1987); this philosophical tradition has similarities with conceptions of causality advanced by Gestalt psychologists (e.g., Michotte, 1946; Wertheimer, 1922, 1923; see also Chapter 4 and Eimer, 1987). For instance, when it rains we have the impression that we can directly perceive the rain making the street wet and changing the street’s colour. Or, when we see a car crashing into another, we seem to directly “perceive” how the first car destroys the second one. In those cases, inferences seem not to be needed to determine the causal relation, e.g., that the rain makes the street wet or that the first car is the cause for the second car’s broken windshield. Note that the position that causality can directly be “perceived” shares Hume’s and Mill’s assumption that temporal and spatial contiguity are central determinants of phenomenal causality. Mill’s idea that repeated observations of co-occurrences of causes and effects is a prerequisite for determining causality is, however, not shared by Ducasse (1924, 1926).

Conceptions of causality also play a central role in different areas of psychology, and they have been introduced independently by various authors to different fields of psychology such as perception (Michotte, 1946), motivation (Rotter, 1954), emotion (Schachter & Singer, 1962), and developmental psychology (Piaget, 1954; Shultz & Kestenbaum, 1985). However, they have been most explicitly dealt with by Fritz Heider (1896–1988), who is considered the founder of attribution theory, the approach to be discussed in the present volume.

Heider published his influential monograph, The Psychology of Interpersonal Relations, in 1958. However, this work did not immediately arouse interest in the topic of causal attributions. In the late 1960s the social psychologists Harold H. Kelley and Edward Jones picked up Heider’s ideas, and systematised and extended them. Their versions of attribution theory spawned hundreds of social psychological research articles on perceived causality (and rekindled interest in Fritz Heider’s book) in the 1970s and 1980s. In these years, attribution theory was the dominant theoretical framework of social psychology, and the theory was also taken up in other basic and applied areas of psychology. Weiner offered an influential attributional analysis of achievement behaviour (see, Weiner et al., 1971; see Chapter 9), and Abramson, Seligman, and Teasdale (1978) introduced their much cited attributional model of learned helplessness (see Chapter 2). These works, in turn, spawned interest in the application of attribution theoretical analyses to the area of educational (see, for a summary, Weiner, 1979), clinical (see, for a summary, Försterling, 1988), health (see Schwarzer, 1992; Taylor, 1983), and organisational psychology (see Baron, 1990; Folkes, 1990). At the turn of the century attribution theory was less often the explicit topic of research articles in the area of social psychology. However, a closer reading of social psychological articles reveals that the studied phenomena often also include or even entirely consist of causal attributions or that attribution-theoretical explanations are being made for many research findings (see, for instance, the analysis of Rudolph and Försterling, 1997). However, the computer-assisted literature search (see Figure 1) revealed that the number of published articles that refer to the keyword “attribution” has hardly decreased within the last few years. Hence, one can conclude that knowledge of attribution became a central building block of social psychology.

The study of perceived causality also continues to “leave” social psychology: Causal or scientific thinking has become an important research topic in the areas of cognitive (see, Cheng, 1997; Waldmann & Holyoak, 1990), developmental (see, Kuhn, 1989), and learning (Shanks, 1989; Shanks & Dickinson, 1988; Wasserman, 1990) psychology, and even animal learning researchers are concerned with whether and how animals “draw causal conclusions” (Premack & Premack, 1994). In addition, attribution approaches are still of increasing importance in the field of applied psychology (see, Graham & Folkes, 1990). Finally, causal cognition is increasingly studied in interdisciplinary contexts, for instance in the interface of anthropology, psychology, philosophy, biology, and law (see Sperber, Premack, & Premack, 1995).

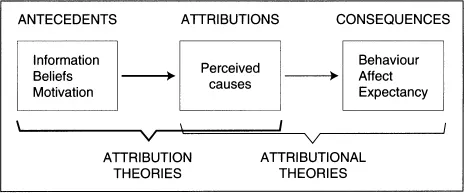

Figure 2. The basic structure of attribution conceptions (according to Kelley & Michela, 1980). (Reprinted with permission from the Annual Review of Psychology, Volume 31 © 1980 by Annual Reviews www.AnnualReviews.org)

The two branches of attribution research

Research that is concerned with causal attributions can—according to Kelley and Michela (1980)—be divided into two subfields (see Figure 2). First, attribution theories are concerned with the antecedent conditions that lead to different causal explanations. For instance, the question of under what circumstances an individual explains failure with lack of ability and when attributions to a difficult task will be made, falls in the area of attribution theories. In research designed to test hypotheses out of attribution theories, the independent variable typically consists of some kind of antecedent information (e.g., it is manipulated as to whether only the focal person failed or whether most individuals failed) and on the side of the dependent variable it is assessed how the participant in the psychological study explains the event (e.g., through lack of ability or the difficulty of the task). Attributional theories, on the other hand, are concerned with the psychological consequences of causal attributions. For instance, they ask questions concerning the emotional consequences of attributing failure to lack of ability versus the difficulty of the task. In attributional studies, causal attributions are typically manipulated as independent variables (e.g., imagine having failed a task due to lack of ability or due to the difficulty of the task), and psychological reactions to the different attributions are assessed as the dependent variable (e.g., the participant is asked to rate how much resignation or anger, respectively, she expects to experience as a consequence of the attribution).

The distinction between attribution and attributional theories also guides the structure of the present book; Part II addresses the anteceden...