![]()

XII

PERSONALITY

Presenting the Thesis That Our Personality is But the Out-growth of the Habits We Form

Introduction:—If a hundred individuals were asked to give a definition of personality, each of the hundred individuals regardless of his walk in life would return an answer, and his answer would differ in many particulars from every other answer. It is a word used by almost everybody from professors of psychology down to newsboys on the street. The behaviorist usually likes to discard psychological words that have no precise meaning and that are so laden down by bad history, but through some perversity of his nature he is trying to keep the term personality because it does fit so beautifully into his general psychological system.

What Does the Behaviorist Mean by Personality ?

All through our study of behavior so far we have had to dissect the individual. We have had to talk about what the individual did in this, in that or in the other situation. My excuse is that it was necessary to look at the wheels before we could understand what the whole machine is good for. In this lecture let us try to think of man as an assembled organic machine ready to run. I mean nothing very difficult by this. Take four wheels with tires, axles, differentials, gas engine, body; put them together and we have an automobile of a sort. The automobile is good for certain kinds of duties. Depending upon its makeup, we use it for one kind of job or another. If it is a Ford, it is good for going to market, for running errands and for driving over the roughest roads and in the most difficult kinds of weather. If it is a Rolls Royce, it is good for pleasure riding, calling on people who are just a little above us in the social scheme, impressing upon those poorer than ourselves that we are persons of wealth, and the like. In a similar way this man, this organic animal, this John Doe, who so far as parts are concerned is made up of head, arms, hands, trunk, legs, feet, toes and nervous, muscular and glandular systems, who has no education and is too old to get it, is good for certain jobs. He is as strong as a mule, can work at manual labor all day long. He is too stupid to lie, too bovine to laugh or play. He will work all right as a “white wing,” as a digger of ditches or as a chopper of wood. Individual William Wilkins, having the same bodily parts but who is good looking, educated, sophisticated, accustomed to good society, travelled, is good for work in many situations—as a diplomat, a politician or a real estate salesman. He, however, was a liar from infancy and could never be trusted in a responsible place. He is too selfish to be placed over other people. He would leave his work in the middle of any afternoon for golf or a bridge game.

Whence come these differences in the machine? In the case of man, all healthy individuals, as we saw in the lectures on Instincts, start out equal. Quite similar words appear in our far-famed Declaration of Independence. The signers of that document were nearer right than one might expect, considering their dense ignorance of psychology. They would have been strictly accurate had the clause “at birth” been inserted after the word equal. It is what happens to individuals after birth that makes one a hewer of wood and a drawer of water, another a diplomat, a thief, a successful business man or a far-famed scientist. What our advocates of freedom in 1776 took no account of is the fact that the Deity himself could not equalize 40-year-old individuals who have had such different environmental trainings as have the American people.

In studying the personality of an individual—what he is good for, what he isn’t good for and what isn’t good for him—we must observe him as he carries out his daily complex activities; not just at this moment or that, but week in and week out, year in and year out, under stress, under temptation, under affluence and under poverty. In other words, in order to write up the personality, the “shop ticket,” for an individual, we must call him in and put him through all the possible tests in the shop before we are in a position to know what kind of person—what kind of organic machine—he is.

What do we mean by putting the individual through his various paces in the world we live in? Well, I have in mind the answers to such questions as these: What kind of work habits has John Doe? What kind of husband does he make? What kind of father? How does he behave toward his subordinates? His superiors? How does he behave toward his partners or equals in whatever group he works? Is he really a man of principle or is he a psalm-singing, sanctimonious individual on Sunday and a grasping, close-fisted, unscrupulous business man on Monday? Is he pleasantly well bred, or is he over-courteous, with accent and mannerisms dependent on the college he grew up in, or the last country he visited? Does he make a faithful friend to friends in need? Will he work hard? Is he cheerful? Does he keep his troubles to himself?

The behaviorist naturally is not interested in his morals, except as a scientist; in fact he doesn’t care what kind of man he is. He must study any individual, though, whenever society calls for analysis. As a scientific man the behaviorist would like to be able to give an answer not only to such questions as we have raised, but to all other questions which could be asked about John Doe. It is a part of the behaviorist’s scientific job to be able to state what the human machine is good for and to render serviceable predictions about its future capacities whenever society needs such information.

Analysis of Personality

In order that there may be no vagueness about the behaviorist’s use of “personality” let me tell you more concretely what I mean by the term. Do you remember the diagram I gave you in Lecture VI (p. 106)? There I talked about the development of the activity stream. I pointed out that at birth and at different intervals thereafter unlearned beginnings of behavior are always present. I pointed out also that most of these unlearned activities begin to become conditioned a few hours after birth. From that time on each such unit of unlearned behavior develops into an ever expanding system. In the chart I gave there we could draw in only a few lines to indicate what happens.

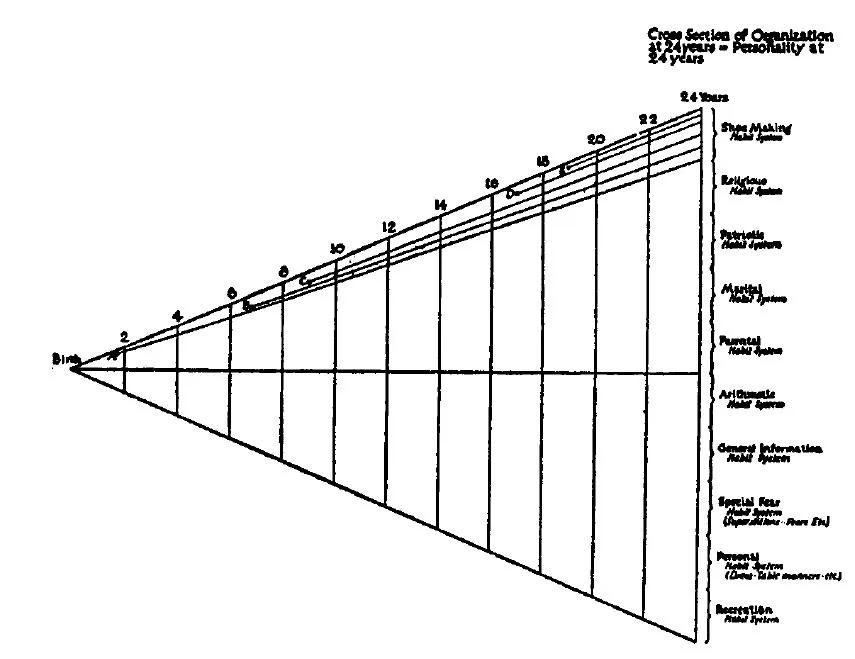

Suppose now that this chart of the activity stream be made complex enough to show the history of every bit of organization the individual has had from infancy to the age of 24. Just assume, for purposes of argument, that the habit curve for everything that you can possibly do had been plotted out by a behaviorist who had studied you under experimental conditions throughout the whole of your life up to the age of 24. Now it is obvious that if at the age of 24 he took a cross section of your activity, he would be able to catalogue everything that you can do. He would find, would he not, that many of these separate activities are related—and please do not accuse me of bringing in the philosophers or Mr. Einstein when I speak of things being related—I mean merely that many activities grow up around the same object such as the family, the church, tennis, shoe making, and so on. Let us stop and look at any habit system at random, such as shoe making for example.

Shoe making, in the old days, meant, first the rearing of cattle, then slaughtering them, then taking the hides to the tan yard. In the tan yard, oak bark was ground up in a horse-driven mill. Vats were dug in the ground, the vats were filled with water and the tan bark was thrown into the vats. Then the hides were dropped into the vats and the tannic acid coming from the oak bark caused the fur to drop off. This is called tanning the leather. After the hides were taken from the vats, they were washed and put through a process of drying and treating. Lasts had to be made for the customers’ shoes, leather had to be cut up and shaped over the lasts. Soles had to be sewed on. It is needless to enumerate every operation that had to be gone through before a finished pair of shoes could result. On my grandfather’s place there was a man who knew every detail of every one of these operations and actually performed them. I would call all of the acts connected with shoe making (of course the group of acts differs considerably from one decade to another because of the specialization going on in labor) the shoe making habit system. You can easily understand that if we broke that system up into the separate activities we should need something like a thousand divisions on a chart just to describe shoe making organization. And to make our chart complete and serviceable in helping us to predict something about the future behavior of an individual’s shoe making activities, we should have to show the age at which each of these habits began to form and their history from that time up to the present time. This whole study would give us the life history of that individual’s shoe making habits.

Now let us turn to another complex system of habits. In talking about the personality of an individual we often hear the phrase, “He is a deeply religious man.” What does that mean? It means that the individual goes to church on Sunday, that he reads the Bible daily, that he says grace at the table, that he sees to it that his wife and children go with him to church, that he tries to convert his neighbor into becoming a religious man and that he engages in many hundreds of other activities all of which are called parts of a modern Christian’s religion. Let us put all of these separate activities together and call them the religious habit system of the individual. Now each of these separate activities making up this system has a dating back in the individual’s past and a history from that point to the age of 24 where we are taking the cross section. For example, he learned the little prayer, “Now I lay me down to sleep,” at 21/2. This habit was put away at 6 and the Lord’s Prayer took its place. Later on, if he entered the Episcopal faith, he read the printed prayers. If a Baptist, Methodist or Presbyterian, he made up his own prayers. At 18 years of age, having certain organization in public speaking, he began to “lead” in prayer meeting. At 4 years of age, he began to look at pictures in the Bible and to have the Bible stories read to him and told to him. He began to go to Sunday School at this time and to memorize certain biblical passages. Soon he was able to read the Bible through and to memorize whole books of it. Again it is far too complex a task for us to attempt to take each of the strands of this religious organization and to trace out its beginning and its genetic history.

So far we have discussed in detail only two of these systems, but the cross section at 24 years of age would show many thousands of such systems. You are already familiar with many of them, such as the marital habit system, the parental system, the public speaking system, the thought systems of the profound thinker, the eating system, the fear system, the love system, the rage system. All of these are broad general classifications, of course, and should be split up into very much smaller systems, but even these divisions will serve to give you a conception of the kinds of facts we are trying to present. Let us draw a diagram to help us hold all of these facts together (Fig. 23)

Possibly you are already impatient to know what all this has to do with personality. I define personality as the sum of activities that can be discovered by actual observation of behavior over a long enough time to give reliable information. In other words, personality is but the end product of our habit systems. Our procedure in studying personality is the making and plotting of a cross section of the activity stream. Among these activities, however, there are dominant systems in the manual field (occupational), in the laryngeal field (great talker, raconteur, silent thinker) and in the visceral field (afraid of people, shy, given to outbursts, having to be petted, and in general what we call emotional). These dominating systems are obvious, easy to observe, and they serve as the basis for most of the rapid judgments we make about the personalities of individuals. It is upon the basis of these few dominant systems that we classify personalities.

This reduction of personality to things which can be seen and observed objectively possibly will not square very well with the sentimental attachments you have for the word personality. It would fit much more easily into your present organization if I did not define the word personality and merely characterized people by saying, “He has a commanding personality,” “She has an appealing and charming personality,” “He has a most disagreeable personality.” But just come to earth a minute and think about this a little. What do you mean by a commanding personality? Isn’t it generally that the individual speaks in an authoritative kind of way, that he has a rather large physique and that he is a little taller than you are?

Another factor that does not come out in the activity chart is this—personality judgments usually are not based purely on the life chart of the individual whose personality is being studied. If the person studying the personality of another were free from slants and if accurate allowance could be made for the effects of his own past habit systems, he would be able to make an objective study. But none of us has this kind of freedom. We are all dominated by our past and our judgments of other people are always clouded by difficulties in our own personality. For example, I spoke above of a ‘dominating’ personality and you nodded your head in agreement. Under the present system of rearing children the father is usually reacted to as though he were a large, powerful man, a kind of superhuman brute who must be obeyed instantly or punishment will be either threatened or applied. Hence you are easily liable, when an individual possessing these characteristics comes into the room, to fall under his ‘spell’ This means nothing more to the behaviorist than an expression of the fact that people who act like your father still have the power to make you behave like a child. It would not be difficult for me to pick out any of these cherished convictions you hold about personality and show it up in its true light.

Fig. 23. Rough diagram to illustrate what the behaviorist means by “personality” and to show how it develops. In examining this diagram refer also to the diagram illustrating the stream of activity on page 106. The central thought in the diagram is that personality is made up of dominant habit systems (only a few of these are shown in the 24-year-old cross section-there are really many hundreds).Note that the cross section at 24 years of age reveals shoemaking as one of the dominant vocational habit systems and that the shoemaking habit system is made up of separate habits, A, B, C, D and E. All of these separate habits are put on at different ages.

All the other habit systems—for instance, the religious, the patriotic, etc.— should have similar lines extending backward into the adolescence, youth and infancy of the individual in order to make them complete. For the sake of clearness, we have omitted them.

In presenting personality in this way, I think it should become clearer to you now how the situation we are in dominates us always and releases one or another of these all-powerful habit systems. For example, the ringing of the Angelus stops the reapers in the field, breaks in on their manual systems and throws them for the time being under the dominance of their religious habit systems. In general, we are what the situation calls for—a respectable person before our preacher and our parents, a hero in front of the ladies, a teetotaler in one group, a bibulous good fellow in another.

One other thing the activity chart fails to show—and one which is of the very greatest importance. In developing so many hundreds and thousands of habit systems it is almost inevitable that these systems must conflict at one time or another. Thus it comes about that one stimulus may call out, or partially call out, two opposed types of action in the same muscular and glandular group. Inaction, fumbling, trembling, etc., may result. In certain cases there are apparently almost permanent conflicts, conflicts of such extent and of such magnitude that a psychopathological individual results. I shall develop this farther on.

In a perfectly integrated (!) individual the following events happen: As soon as a situation begins to call for the dominance of a certain habit system, the whole body begins to unlock: the tensions in every set of striped and unstriped muscles not to be used in the immediately forthcoming action are released so as to free all of the striped and unstriped muscles and glands of the body for the habit system now needed. Only the one habit system the operation of which is called for can work at the maximum efficiency. The whole individual thus becomes ‘expressed’ his whole personality is ‘engrossed,’ in the act he is doing.

May I diverge here just a moment to say that this way of looking at the dominance of habit systems removes from the psychology of the behaviorist any need of the term attention?? Attention is merely then, with us, synonymous with the complete dominance of any one habit system, be that a verbal habit system, a manual habit system or a visceral one. “Distraction of attention,” on the other hand, is merely an expression of the fact that the situation does not immediately lead to dominance of any one habit system, but first to one and then to the other. The individual starts to do one thing but falls under the partial dominance of another stimulus which partially frees another habit system. This leads to a conflict in the use of certain muscle groups. A fumbling of speech may result, a fumbling with the hands or the body may result, or an insufficient amount of energy may be released for use of the muscle groups. Some examples are these: Just as you are taking the high jump your schoolboy friend derides you; when you are just fixing to take your swing in golf somebody speaks; when you are deeply engaged in thinking out a problem the water begins to drip in the bathroom: action is interfered with or even fails altogether. Illustrations of the attempted double and triple (and sometimes multiple) dominance of habit systems are very numerous. For these reasons the behaviorist feels that the term “attention” has no application in psychology and is just another confession of our inability to think clearly, and to keep mystery out of psychological terms. We like to keep mystery in so we can use it on a rainy day—when we are ill or low or particularly dissatisfied with what we are getting out of this existence of ours. Then we begin to think that since everything is footless here, there must be something somewhere else.

How to Study Personality

In youth personality changes rapidly:—Naturally if personality is but a cross section at any given age of the complete organization of an individual, you can see that this cross section must change at least slightly every day—but not too rapidly for us to get a fair picture from time to time. Personality changes most rapidly in youth when habit patterns are forming, maturing and changing. Between 15 and 18 a female changes from a child to a woman. At 15 she is but the playmate of boys and girls of her own age. At 18 she becomes a sex object to every man. After 30 personality changes very slowly owing to the fact, as we brought out in our study of habit formation, that by that time most individuals, unless constantly stimulated by a new environment, are pretty well settled into a humdrum way of living. Habit patterns become set. If you have an adequate picture of the average individual at 30 you will have it with few changes for the rest of that individual’s life—as most lives are lived. A quacking, gossiping, neighbor-spying, disaster-enjoying woman of 30 will be, unless a miracle happens, the same at 40 and still the same at 60.

Different Ways of Studying Personality

Most people pass their judgments on the personalities of their associates without ever having made a real study of the individual. In our rapidly sh...