eBook - ePub

Inequality and Stratification

Race, Class, and Gender

Robert A. Rothman

This is a test

Share book

- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Inequality and Stratification

Race, Class, and Gender

Robert A. Rothman

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

For undergraduate courses in Social Stratification, Race, Class, and Gender, and Introduction to Gender Studies. Using a concise and easy-to-understand style, this text provides an integrated approach to the implications of social class, race and ethnicity, and gender-explaining how each relates to economic, social, and political inequality.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Inequality and Stratification an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Inequality and Stratification by Robert A. Rothman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Scienze sociali & Sociologia. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

THE NATURE OF INEQUALITY AND STRATIFICATION

Industrial societies are distinguished by several prominent social divisions—social classes based on position in the economic system of production and distribution, sex and gender, and racial and ethnic categories. Many of the most significant rewards and advantages available to people are shaped by these three factors. The consequences of class, race or ethnicity, and gender are most pronounced in areas such as the distribution of earnings and wealth, judgments and evaluations of social prestige, access to political power, and life chances such as the risk of illness and access to health care, crime and justice, and educational opportunities. The system of classes, races, ethnic groups, and genders and the distribution of inequalities are supported and maintained by the culture and social structure of the country in which they exist. Chapter 1 develops the basic ideas and concepts central to the sociological analysis of inequality and stratification. Chapter 2 reviews the major theoretical conceptualizations and interpretations of the origins of industrial social systems that dominate current theory and research.

CHAPTER ONE

Inequality and Social Stratification

THE FORMS OF INEQUALITY

The scope of inequality in the contemporary world is obvious. Discrepancies—sometimes vast discrepancies—in wealth, material possessions, power and authority, prestige, and access to education, health care, and simple creature comforts dominate the social life of societies. At the extremes are the homeless and the super-rich, the esteemed and the degraded, the powerful and the powerless, and many levels between them. There are many forms of inequality, but since the nineteenth century, sociologists have tended to focus on three major forms—economic, social, and political—an analytic practice first suggested by the pioneering German sociologist Max Weber.

Economic Inequalities

Disparities in wealth and material resources are usually the most visible form of inequality. Industrial societies contain millions of people whose daily lives are a struggle against calamity. More than 43 million Americans have no health insurance, and 8.5 million of them are children (Mills and Bhandari, 2003). One child in ten lives in poverty in major industrial nations—Australia, Britain, Canada, Ireland, Israel, and Italy (Pear, 1996). In America, it is one child in five! Hundreds of thousands of the destitute are homeless, compelled to wander the streets and fill the shelters in New York, Los Angles, London, and Moscow. Between 900,000 and 1.4 million American children are homeless for some period in any given year (Egan, 2002).

While many struggle for survival, others in the same society enjoy the benefits of great wealth. Professional athletes, entertainers, corporate executives, and e-business entrepreneurs earn millions of dollars each year. Others, fortunate enough to have been born into prosperous families with names such as duPont or Hilton or Walton (Wal-Mart), never need to worry about the source of their next meal or confront the fear of being unable to pay the rent. On the contrary, some of the very rich indulge unbelievably ostentatious and extravagant lifestyles. One couple flies their palm trees from Southampton, New York to Palm Beach, Florida in the winter months to keep them warm (Yazigi, 1999). Wealthy tobacco heiress Doris Duke always felt it necessary to fly her two pet camels with her on trips to Hawaii (Clancy, 1988). Ranged between such extremes are smaller gradations of monetary inequality, often measured by the size of homes and the quality of their neighborhoods, the kind of cars people drive, or the quality of the schools their children can afford to attend.

Social Status

A second important form of inequality is social status. Social status is the social standing, esteem, respect, or prestige that people command from other members of society. It is a judgment of the relative ranking of individuals and groups on scales of social superiority and inferiority. Social status is a relevant prize because people are highly sensitive to the evaluations of others, valuing the admiration and approval of their peers as is readily evident when they attempt to embellish their social standing through the public display of designer clothing and jewelry, luxury cars, and homes. An individual might be able to write equally well with a Bic pen as with a Mont Blanc, but only the latter confers social status.

Individuals can earn social status on the basis of their own efforts (athletic ability) or personal attributes (physical attractiveness, intelligence), but there is also a powerful structural dimension to social status—occupations, social classes, racial and ethnic groups, and the sexes are typically ranked relative to one another. For example, at various times and in various places, women and men have formed clearly demarcated status groups. In the United States, it was common for males to be openly rated as superior to females by both men and women well into the 1950s and 1960s (McKee and Sherriffs, 1957). Occupational prestige rankings are probably the status hierarchies with which most people are familiar. Occupations around the world are typically arranged on a strict hierarchy of prestige, usually with physicians, lawyers, and scientists at the top and garbage collectors and janitors near the bottom.

The significance of social ranking extends beyond questions of social approval and ego gratification. Status considerations can dictate the form of social interaction between people at different levels. People are likely to show courtesy to those ranked above them, but they tend to expect deference from those ranked below them. Social considerations also lead to practices designed to limit social contacts with people defined as inferior, which shows up in residential segregation, club memberships, and other forms of exclusionary behavior.

Power and Authority

A third salient form of inequality deals with the unequal distribution of power and authority in society. Although there is a lack of consensus on precise definitions of such terms, there is general agreement that the essence of power is the ability to control events or to determine the behavior of others in the face of resistance, and to resist attempts at control by others. Authority refers to a specific form of control where the right to command is considered as appropriate and legitimate. Authority may be based on tradition, or it may reside in organizational position (as with a marine general’s right to direct the behavior of lieutenants or a supervisor’s ability to sanction workers) or in expert knowledge (a lawyer’s capacity to prescribe the actions of clients).

Discrepancies in power are often difficult to document, but it has long been recognized that enormous power is concentrated in the hands of the people who head the large organizations that dominate the business, governmental, and military landscape. Sociologist C. Wright Mills (1956) focused on a small “power elite” of corporate executives, military officers, and political leaders who exercised unusual control over the direction of the nation’s affairs. A few years later, President Dwight Eisenhower warned of a powerful “military-industrial” complex in his farewell address. At the other end of the spectrum are the majority of Americans who feel quite powerless politically, believing they have little or no influence over the activities of the government. For example, three out of four people feel that large corporations have too much influence over government (A. Bernstein, 2000).

Life Chances

Economic, social, and political inequalities are direct and have readily observable consequences, but there are also subtle and less obvious forms of inequality. Max Weber (1946) introduced the concept of life chances to identify the role of social class in enhancing or weakening the probability of enjoying experiences that enhance the quality of life or facing barriers that diminish it. It is appropriate in contemporary analysis to extend the term life chances to include the implications of race, ethnicity, and gender as well as class. Life chances include the odds of newborns surviving infancy; the chances of going to college; the risk of suffering mental illness, loneliness, or obesity; and the probability of being a victim of violent crime such as robbery, assault, or rape.

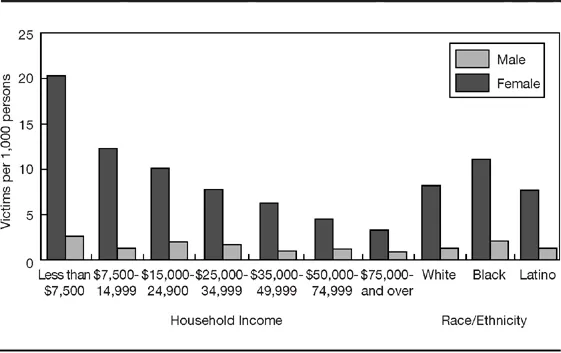

The idea of life chances is highlighted by considering the problem of domestic violence or what is now called “intimate partner violence.” About 1 million cases of violent crimes are committed by current or former spouses, boyfriends, or girlfriends each year. Murder, rape, sexual assault, robbery, and aggravated and simple assault are included as violent crimes, and 85 percent of the victims are women. The chances of falling victim to violence are not evenly distributed across the stratification system, as shown in Exhibit 1.1. Women in the poorest households are almost seven times as likely to be harmed as those in the top income group. Race also makes a difference, with African-American women victimized more frequently than any other group. These numbers can only hint at the scope and significance of social stratification.

EXHIBIT 1.1 Intimate Partner Violence by Household Income, Race, Ethnicity, and Gender

Note: Victims per 1,000 females or males.

Source: Callie Marie Rennison and Susan Welchans. Intimate Partner Violence. U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2000.

Social Stratification

The phrase social stratification is a general term used to refer to the hierarchy of layers or divisions of individuals and families in a society where position is a major source of rewards. Social stratification has taken many forms in different places and at different points in history, but the three most familiar forms are slave, caste, and class systems. Each form arises under different historical conditions, singles out distinctive social categories of people, generates alternative kinds of hierarchies, and differs in the scope and magnitude of inequalities.

Slave systems divide people into two fundamental groups, the free and the unfree. Slavery is forced labor imposed by physical or mental coercion, where the employer or owner exerts virtually complete control over people, including the right to buy or sell them. Slavery has been a recognized aspect of many societies. The enslavement of one group by another is, in fact, as old as recorded history, with slaves found in domestic work or in large gangs for agriculture or large-scale construction projects in ancient Mesopotamia, India, China, and Egypt. Despite a great deal of progress in the area of global human rights, slavery survives in a number of places around the globe, such as Mauritania (Masland, et al., 1992; Burkett, 1997; R. Segal, 2002).

Today a worldwide underworld system of trafficking in women and children is a modern form of slavery that penetrates even into the United States. As many as 700,000 women and children are forced into bondage each year according to a recent CIA report (Brinkley, 2000). Some are physically seized and transported while other victims are enticed by promises of legitimate jobs in industrial nations, but upon reaching their destination are forced to work as prostitutes, domestics, or common laborers. It is estimated that between 50,000 and 100,000 of this group were transported to America in recent years. The Department of Justice has stepped up prosecution of ringleaders since the passage of the Trafficking Victim Protection Act of 2000, but countless poor and vulnerable women and children from Eastern Europe, Asia, and African countries continue to become ensnarled in the secretive and treacherous slave trade.

Caste systems organize people into fixed hereditary groups in which there is little or no chance for children to escape the caste of their parents. Caste systems have existed at various times in Rwanda (East Africa), Japan, Tibet, Korea, India, and Pakistan. The most well known, the Hindu caste system, was in place as early as the ninth century and prevailed until the nineteenth century. Members of different castes were allocated to specific occupations, and social contacts between castes were regulated by elaborate rituals. The British began to formally dismantle the system in the nineteenth century, but vestiges remain in many rural areas (Beteille, 1992). The dilemmas of the caste system are aggravated by the devaluation of females. Scarce resources are allocated to males while infant girls and women are often malnourished (M. Cooper, 1997).

Social Class

The term social class is defined and measured in a number of different ways in the social sciences (Grusky and Sorensen, 1998). Some researchers emphasize income while others focus on education, occupation, or self-direction in the workplace, but there is consensus that social class position is embedded in industrial economic systems. Therefore, social class is here def...