eBook - ePub

Criminology: The Basics

Sandra Walklate

This is a test

- 238 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Criminology: The Basics

Sandra Walklate

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Criminology is a discipline that is constituted by its subject matter rather than being bound by an agreed set of concepts or way of thinking. This fully updated third edition of Criminology: The Basics is a lively and engaging guide to this compelling and complex subject. Topics covered include:

-

- the history and development of criminology

-

- myths about crime and offenders

-

- the search for criminological explanation

-

- victims of crime and state crime

-

- crime prevention, cybercrime, and the future of crime control

-

- criminology and intersectionality

This edition also includes new sections on genocide, terrorism, cultural victimology, and Westo-centric thinking.

Concise and accessible, this book utilises chapter summaries, exercise questions and lists of further reading to provide a perfect introduction to this subject.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Criminology: The Basics an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Criminology: The Basics by Sandra Walklate in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Research & Methodology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 WHAT IS CRIMINOLOGY?

The purpose of this chapter is to get a sense of criminology as an academic subject. In order to do this we shall explore some features of the origins of the discipline and how those features still influence what it is that criminologists do, and do not do, today. In particular, this chapter will explore popular media images of crime and offer good reasons as to why those images are misplaced when compared with the historical development of criminology, and its sister discipline, victimology. This exploration will help us understand how the boundaries of the discipline have been set and who is included and excluded by those boundaries. At the end of this chapter we shall use a case study, that of the U.K. serial murderer Harold Shipman, to establish the extent to which the boundaries of criminological and victimological knowledge can help us make sense of behaviour like this.

INTRODUCTION

Before it is possible to say what criminology is, it is important to have some understanding of what it is not. Disciplines like politics, sociology, economics, or psychoanalysis are held together by some common agreement on their subject matter. In the case of politics, an understanding of different political processes; for sociology, the structure of society; for economics, the nature of economies; or in the case of psychoanalysis, the individual psyche. This common agreement gives these disciplines their central focus regardless of the social or legal context in which they are practiced. Of course, that social or legal context may add variety to the kinds of analyses those various disciplines offer but the conceptual and analytical frameworks within which the disciplines operate remain very similar. The same cannot be said for criminology. Criminology is inevitably a different creature since in some respects its focus is dependent upon how crime itself is brought into being in different social and legal contexts. So what might be understood as crime, and as criminal, in France may vary from how that is understood in the United States. Appreciating and understanding the importance of differences like these is the central challenge of a book of this kind for both the author and the reader. There is, however, another challenge. This lies within the potential influence of contemporary media images of crime. How the media represents crime, what constitutes crime and the criminal, and what the criminologist actually does can be, and frequently are, different. A key issue arises then around understanding the extent to which such media images gel with what we think we ‘know’ about crime and what criminologists ‘know’ about crime.

The subject matter of crime is a very popular source of entertainment. Indeed for many people what they see on the television or what they read in the newspapers is their only source of information about crime since, despite variable crime rates over the last 30 years or so, most people most of the time have no experience of their own about crime or the criminal justice process. This makes media images of crime potentially very powerful especially in equipping individuals with ideas about what it is that criminologists do. However, the presence of Sherlock Holmes, Inspector Poirot, crime scene investigators (“CSI”), other ‘detective’ stories, and the forensic psychologists, (“The Mentalist” and so on) popularised in the media notwithstanding, what these people claim to do, how crime is dealt with in ‘real’ life, and what criminologists actually spend their time doing are quite distinct activities. In particular, criminology is not concerned with ways of catching criminals. That is the work on the one hand of a good police officer and on the other a good supply of information from the general public. Criminology is much more concerned with explaining the cause(s) of crime. However, how it does so will very much depend on what kind of criminologist you are and what kind of theory you choose to work with. In Chapter 4 we shall discuss the role that theory plays in characterising different criminology.

Paul Rock (1986), a British sociologist, once described criminology as a ‘rendezvous’ subject. This is a way of trying to capture a sense of what, if anything, binds criminologists together. Put simply, it is the subject matter of crime. Why make an issue of what seems to be fairly obvious? Of course criminologists are interested in crime. However, exploring this obvious fact is what makes criminology as an area of investigation somewhat different than other areas of investigation. Psychologists, for example, explore how the mind works, sociologists are interested in social structures, economists in economic systems, historians are interested in how what happened in the past can help us better understand the present, and so on. Each of these different disciplines is characterised by the boundaries between them and how they go about their business in relation to what it is that they study: the past, society, the mind, the economy, etc. However, within these boundaries they can all be interested in crime. So what binds criminologists together is that they share an interest in the same subject matter, crime, but importantly they do not necessarily share the same way of thinking about how to study that subject matter. So criminology, as Rock said, is a meeting place for people with different ways of thinking about crime. It is multidisciplinary. So it is possible to find psychiatrists, historians, sociologists, psychologists, lawyers, and economists who all claim the label ‘criminologist’ but might be looking at the question of crime though very different lenses. Criminology, as a consequence, is characterised by debate. There are very few things that criminologists agree upon. One thing, however, that they may all share concerns about is what it is that we understand by crime. How is crime to be defined?

WHAT IS CRIME?

Again, this seems an obvious question to ask. We ‘all know’ that crime is behaviour that breaks the law. However, is it so straightforward? Even the Sage Dictionary of Criminology (2006) makes it clear that what we mean by ‘crime’ is highly contested. So what might that contest look like? If we take law breaking behaviour as the starting point for our understanding of what we mean by crime, and thereby what it is that criminologists study, then this raises at least three issues.

• First, if it is the law that defines what it is that is criminal this clearly separates what we mean by the criminal from the rather more emotional use of the term. This in some respects is a useful starting point though it is not without its problems. The term criminal can, on the one hand, prejudge the guilt or innocence of the offender, and on the other it can also tap into notions of ‘wickedness’ or ‘evil’ doing. In these respects, it may be more helpful to say that criminologists are interested in law breaking behaviour. However, this definition is in itself problematic because it gives a status to the law as though this were above social processes that lie behind the formation of the law, for example, levels of tolerance and acceptability of different behaviours. This is clearly not the case.

• So, second, making what is and is not legal the defining characteristic of what it is that criminologists study places the law at the centre of the criminological stage. The law defines what is and is not a crime. However, it must be remembered that over time laws change. Some behaviours are newly defined as criminal (law breaking) others are decriminalised (defined as non-law breaking). (Think, for example, about the changing legal status of ‘being gay’ over time and in different places). This being the case, the key question that follows is what processes produce such changes? Moreover, who influences such changes and how are they implemented? Is it an understanding of these processes that produces an understanding of crime? This is quite a different question than a psychologist interested in crime might ask. They might be much more interested in what kinds of personality types predispose some individuals to engage in criminal behaviour. Such behaviour might occur, of course, regardless of the actual content of the law but may nevertheless be problematic (this is what sociologists call ‘deviant’ behaviour).

• However, there is a third difficulty in taking the law as defining what is crime. If this is taken as the defining characteristic of the criminal, does that mean that criminologists then can only legitimately study those who have been found guilty of transgressing the law? For many criminologists, this kind of position would prove to be highly problematic given its inherently narrow focus on those individuals who have been caught and successfully prosecuted.

• Following on from this, a fourth problem might be the extent to which crime has a reality above and beyond the processes that bring crime into being: the law and the criminal justice process. This has led some criminologists to argue that because this is so variable in different social contexts crime has no real meaning outside of those contexts. For them, sometimes referred to as zemiologists, harm matters more than crime and we shall return to this later in this book.

So from this discussion it can be seen that what counts as crime and thereby what criminologists study is neither consistent nor uniform. Moreover, if the focus of criminology is law-breaking, then this will vary from country to country and over time. Putting all of this together with the different ways in which people think about what counts as crime, we can identify at least six different understandings of what crime is.

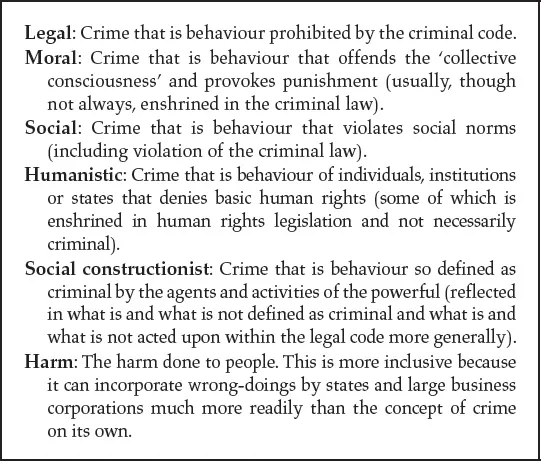

Figure 1.1 Different understandings of what crime is.

Figure 1.1 illustrates some of the different ways in which crime can be, and has been, defined by criminologists. As can be seen, they each in their different way take the law as a starting point for their understanding of crime but only the legal understanding takes the criminal code as the definitive start. Figure 1.1 also illustrates the way in which these different definitions harness different understandings of what Henry (2006: 78), a North American criminologist, has called the determining elements of crime. He suggests that there are three:

1. Harm (nature, severity, extent of the act committed, and/or the kind of victim the act has been committed against).

2. Social agreement or consensus (the extent to which there is social agreement that the victim has been harmed).

3. Official societal response (whether or not there is a law that specifies the act committed as a crime or not and how those laws are enforced).

So far from being straightforward, defining what crime is can be quite complex. This complexity arises as a result of a number of questions being muddled up; what crime is, who the criminal is, and what it is that criminologists study. (Moreover, Henry’s definition above introduces another dimension to what it is that criminologists study: the victim of crime, see also below.) Some of this complexity relates to the fact that this is a multidisciplinary area of concern and some of it reflects the historical focus that criminology has had in trying to formulate a general theory of crime. As a consequence, it is possible to define the subject matter of criminology in different ways. For example:

Coleman and Norris (2000: 13–14) identify the subject matter of criminology in the following way:

• An attempt to measure the extent of crime and offenders

• An analysis of the causes of crime

• Understanding how laws are formed

• Understanding how laws are applied

• Understanding issues around punishment

• Crime prevention

• Exploring the impact of crime on victims

• Exploring public attitudes and media presentations of crime

As can be seen, this is quite a wide-ranging list of topics. Newburn (2007: 6) focuses this list by defining criminology as:

• The study of crime

• The study of those who commit crime

• The study of the criminal justice and penal systems

On the other hand, Walklate (2007: 14) defines the key features of criminology in a different way. She states criminology as a discipline is:

• Held together by one substantive concern: crime.

• It is multidisciplinary so it is important to understand the conceptual apparatus with which a particular criminologist might be working.

• Criminologists disagree with each other especially over how to ‘solve’ the crime problem; they nevertheless are concerned to offer some advice on policy.

• What criminologists do sometimes resonates with common sense thinking about crime but often challenges that thinking.

• All of these features of criminology need to be situated within societies increasingly preoccupied with crime, risk and insecurity.

If we put these lists together, then it is clear to see that the discipline itself, if it has claims to such a title, is not only wide-ranging but also highly stimulating and frustrating in the debates that it generates.

In this book we shall be taking primarily a sociological orientation to understanding criminology and in so doing we will cover issues that include problems of measurement, understanding the victim of crime, and looking at the relationship between criminology and crime prevention amongst other issues. However, there is one over-riding concern that is implicit to all of the lists above and in much of criminology. That concern is with trying to identify and understand the causes of crime.

As Figure 1.1 implies, the importance of formulating a general theory of crime has led different versions of criminology to resolve the question of what is crime in different ways, pointing to not only its multidisciplinarity but also to its theoretical diversity. This emphasises the highly contested nature of the discipline and what it is that criminologists study. In an effort to unravel some of this complexity, we shall now consider the history of criminology in more detail. In order to do that, it is important to appreciate and understand a central feature that has underpinned much criminological work: positivism.

THE EMERGENCE OF CRIMINOLOGY AS A DISCIPLINE: THE EUROPEAN CONNECTION

Criminology, like many other academic disciplines, was driven by the concerns of the post-Enlightenment period. This was a time in history when the natural sciences were embraced as constituting a better knowledge base than religion for understanding and controlling nature (which Bacon, a philosopher of science, defined as female and a point to which we shall return in understanding criminology). In their wake, the social sciences followed suit in looking for ways to better manage (read: control) social problems. Post the French revolution and Industrial revolution, Auguste Comte, a French social theorist, was particularly influential in formulating an early version of sociology (that he called social physics) whose role he saw as exerting a positive influence on society. This is one way of understanding the term positivism that was to have so much of an influence on the emergence of criminology as a discipline.

In criminology positivism has been, and still is, very powerful in defining what it is that criminologists do and do not study. Criminology embraced Comte’s understanding of positivism and its historically significant links with policy in wanting to manage social problems. Criminology also embraced a more philosophical understanding of positivism in its efforts to model itself on the natural sciences. That understanding of positivism, a concern with measuring the appearance of things and on the basis of that measurement formulating universal explanations of them, was to provide criminology with the evidential base on which to assert its influence on the policy-making process. This gave early criminology three central characteristics: differentiation, pathology, and determinism.

• Differentiation refers to the desire to measure the differences between individuals and their behaviour.

• Pathology refers to the process of assigning abnormality to those differences.

• Determinism reflects a concern with understanding how factors beyond the control of human beings affect their behaviour.

These ideas underpin the work of one of the most famous and influential criminologists of the nineteenth century, the Italian prison psychiatrist, Cesare Lombroso.

Lombroso is probably best described as a criminal anthropologist whose work was very much influenced by the ideas of Charles Darwin. Darwin’s theory of evolution has one key law: the law of biogenetics. This law states that every organism revisits the development of its own species within its own developmental history. Hence, the human embryo goes through various stag...