![]()

Setting the Scene

FAMILY CHANGES, FAMILY CONTINUITIES

Families have always been changing.

Sometimes fast and at other times slowly, U.S. marriages, relationships to relatives, number of children, and other family matters have been transformed since Colonial days. In addition, history and anthropology tell us that family change has been a world reality. But there have been continuities, too. Family forms may have changed, but there has been a constant commitment to some form of family living.

Let us look at same-sex marriages. Since the late 1980s, some European nations have recognized a modified form of marriage for same-sex couples. They enjoy many, but not all of the legal rights and responsibilities of heterosexual married couples. During the first three years of this century, same-sex marriage became legal in the Netherlands and Belgium. Heterosexual and same-sex couples enjoy all the same rights and responsibilities. (For more details, see ch. 4.)

Meanwhile, in the U.S., it seemed during the 1990s that Hawaii would legalize same-sex marriage, but citizens voted against it in 1998. In 2000, Vermont became the first state to create “civil unions” for same-sex couples, which, like their European predecessors, grant them some, but not all, rights of heterosexual marriages. In late 2003, it seems that it’s only a matter of time before same-sex marriage becomes a reality in the United States. In April, a Massachusetts poll showed that 50 percent of respondents favored it; 44 percent did not, 6 percent were unsure. Each time I take anonymous polls in my sociology classes, 90 percent or more of the students say they approve of it.

The impending arrival of same-sex marriage seems only fair and just to many people. Others, however, are filled with fear and dread. They think it will undermine and destroy traditional marriage. When a state or federal court, or state or national legislative body, approves same-sex marriage, the debate and the conflict over its meaning and consequences will be with us for decades. Few of us would have predicted, even ten years ago, that two men or two women would be granted the same social recognition and legal rights that a man and a woman have enjoyed for thousands of years. No doubt, millions of people are profoundly bewildered; others celebrate; and still others shudder at the coming of same-sex marriage.

But however we feel, let us remember that same-sex couples are seeking to enjoy the rights and responsibilities of marriage, one of the oldest human institutions. They value, honor, and long for marriage. They do not seek to abolish it. What could be more conventional than wanting to create a family, to have a home and children? Same-sex marriage shows both sweeping change in families and profound continuity.

But gay and lesbian families are already with us, even if not yet legally recognized. They have homes and some are raising children. They celebrate, have fun, and worry about their lives, just as traditional families do. In Provincetown, Massachusetts, family weeks for same-sex couples and their children have been celebrated for some years (Capps, 2002; Stacey, 2003).

Family changes are many. Some are problematic, others beneficial. We’ll explore them throughout this book. For example, people are marrying later, and a few are not marrying at all; but most people marry at least once in their life, and many others cohabit for long periods. Women are having fewer children, and they are having them later, but about 90 percent of women do bear at least one child in their lives, and some others are adopting.

Those of us who are older (I was born in 1941) sometimes regret the loss of traditions and practices that were comfortable and enjoyable. But at least to some of us, other changes are welcome. For example, we would not to return to the days when abused women suffered in silence, because we ignored their existence and their plight.

SEVEN FAMILY SCENES

At this point, you may ask, what is a family if we come to define same-sex couples as families. If you know some history and anthropology, you may wonder what the many different groupings people have called families in history share in common. Before we define family directly, we may benefit by looking at a few historical examples of families. I chose them because they cover a wide geographical and historical range. Reading them may enable us to appreciate the nature and variety of families. After you read these seven descriptions, I will make a few summary comments. But I hope that you read, appreciate, and reflect about them on your own first.

Plymouth Colony, 1680s

In A Little Commonwealth: Family Life in Plymouth Colony (1970), John Demos presents a detailed and rich portrait of families and family living in that colony during the 1680s.

Let us begin by dispelling the common belief that in the past the United States was populated by large, three-generation families, “a large assemblage of persons spanning several generations and a variety of kinship connections, all gathered under one roof.” In fact, “small and essentially nuclear families” were the norm in Plymouth, and probably throughout the United States for all its history (Demos, 1970, p. 62). In Bristol in 1689, households averaged six people.

But in many other ways Plymouth families did differ from contemporary ones. Couples had many children; “eight to nine children apiece was pretty standard.” These children were born over many years; for example, “the household of a man forty-five years old might well contain a full-grown son about to marry and begin his own farm, and an infant still at the breast, not to mention all of the children in-between” (Demos, 1970, pp. 68–69).

These households were often augmented for periods of time by non-family members living with the family. For example, men were hired to help with some tasks for a given period; children and adults from other families lived with a family while they learned a trade from the man of the house; and petty criminals “were obliged to become servants [to a family] as an act of discipline initiated by the community at large” (Demos, 1970, p. 70).

Some households decreased in size, while others increased, when illiterate parents would send their children to live with other families who taught them to read and write. Some poor families would send their young children to live as servants with wealthier ones. Family and household size was affected in other ways still. When they were old and unable to care for themselves, aged parents would go stay with their grown children. Adult single men and women would live with their parents or siblings. And finally, sick or homeless people without families were placed by the community to live with families.

All these people lived in fairly small homes, by contemporary standards, the equivalent of two to three room houses. The “hall,” the main room, was the scene of many activities: “Cooking, eating, spinning, sewing, carpentry, prayer, schooling, entertaining, and even sleeping …; and each [activity] demanded its own props” (Demos, 1970, p. 39). (We shall return to Plymouth Colony in later chapters.)

A Kentucky Mountain Family, 1887–1946

In What My Heart Wants to Tell (1979), Verna Mae Slone tells the story of her family. Her parents were married in 1887 and had twelve children. Verna Mae, the youngest, was born in 1914.

They led a simple life. They worked hard, raising and making almost all they ate and used. But work was also fun, talking with family and friends while they worked, or with people as they passed by. Dinners were enjoyable occasions, often including passing neighbors; “when anyone passed the house he was asked to come in…. This was a very strict code of the hills….” Storytelling by family and friends was the major entertainment. “There were many great storytellers. We had few books and listening to these stories was our only entertainment of this kind” (Slone, 1979, pp. 47, 95).

Men and women had many skills, learning them from parents, siblings, and neighbors. They built their own homes; made their furniture and tools; knew much about many plants and herbs; could tell time by the sun and the weather by the chimney smoke; and possessed much other knowledge they needed to survive, which they acquired in their families and communities.

In her loving tribute to her parents and family, Slone also presents conflicts, contradictions, and difficulties. But she primarily describes large families that worked together and cooperated with their neighbors; had fun in their work and socializing; shared memories of their times together; and were close to family, community, and nature.

An Italian Family, 1910s–1930s

In Mount Allegro (1942), Jerre Mangione presents a warm and loving account of his childhood years with his family in Rochester, New York.

His parents, Sicilian immigrants who spoke little English, had four children. But their family extended to uncles, aunts, cousins, other relatives, and some friends. They saw each other often, for long and large Sunday dinners and many weekday gatherings of cards and socializing.

Any excuse sufficed for a large family gathering. Parties, celebrations, and other occasions brought many relatives together for talk, food, and singing. His relatives had “a magnificent talent for gregariousness and a pathetic dread of being alone.” They “seemed happiest when they were crowded in a stuffy room noisy with chatter and children” (Mangione, 1942, p. 23).

When Mangione decided to go away to college, his relatives were shocked. “When I broke the news that I was going to an out-of-town university—Syracuse—my relatives were plainly horrified. Could it be that I was becoming a calloused American? The idea that I could bear to leave them behind offended some of them. They began to regard me as a heretic. A good Sicilian son stuck near his family; the only time he left it was to marry, and even then he lived close by so that he could see his relatives often. Life, after all, was being with each other. You never left your flesh and blood of your own free will. You left only when it was impossible to earn a living near them, or when you died” (Mangione, 1942, p. 227).

On some Sunday nights, after his aunts and uncles had left following a big Sunday gathering and dinner cooked by his father, they would return late at night and serenade the Mangione household. “They stood under our bedroom windows and sang gently until some member of the household awoke; and when they saw a light go on, their singing became louder and more joyous, breaking into an uproarious crescendo as the door was opened to them” (Mangione, 1942, p. 21).

On one occasion, his parents gave a banquet for some relatives who were leaving for California. When they changed their minds and they stayed in Rochester, his parents gave another banquet to celebrate their staying.

Like Slone, Mangione remembers hours of telling long and elaborate stories, most of them by his uncle Nino.

The intense closeness and socializing sometimes led to angry family squabbles. For example, not all relatives could fit in at any one social gathering, and those who were not invited sometimes vocalized their discontent. The arguments would be bitter and people would not speak to each other for months and even years. Other relatives would set in motion elaborate plans to reconcile the disputing parties. And the frequent gatherings and intense socializing seemed suffocating and oppressive to some people.

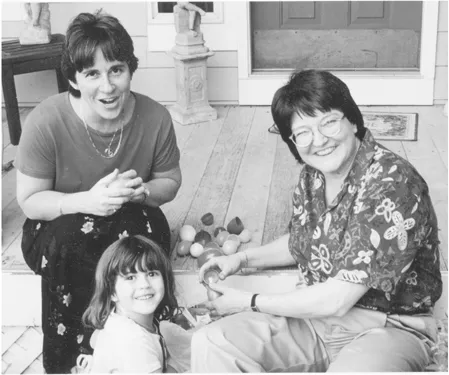

A Lesbian Family, 1990s

In Family Values: A Lesbian Mother’s Fight for Her Son (1993), Phyllis Burke tells the story of her partner Cheryl and their son Jesse. Burke had been unsure about bringing a child into a world unkind to gays and lesbians. “I was afraid. If I loved the baby as much as I might, I wouldn’t be able to stand the pain if the world treated him cruelly” (pp. 7–8).

Cheryl, however, was absolutely certain she wanted a child because “I want the meaning in my life that only a child can give.” In time Cheryl convinced Burke, and Cheryl became pregnant through “assisted conception, which is what donor insemination has come to be called.” Burke continued to struggle with her feelings. How should she relate to the child? She would not be its mother or father. “I decided, Yes, I will help Cheryl raise the baby, but I would be his aunt. He would call me Aunt Phyllis…” (Burke, 1993, pp. 5–8).

This young girl has two legal mothers—her biological mother and her adopted mother. Although not identical, the story of this family is similar to that of Cheryl and Phyllis.

They attended Lamaze classes together, where the straight couples assumed Burke was Cheryl’s friend, even though Cheryl introduced her as “my partner.” Jesse was born and they instantly fell in love with him and raised him together. Jesse sabotaged Burke’s plan to be “Aunt Phyllis” by calling her “Mama.”

“Jesse looked at me and smiled.

“‘Mama,’ he said.

“I looked at him…. He smiled with satisfaction. He had never said this word. It sounded so sweet and alien to me.

“‘No dear,’ I corrected him.‘Auntie, Auntie….’

“He tossed his head back and laughed.‘Mama. Mama’” (Burke, 1993, p. 33).

In time, Jesse called them “Mama Cher” and “Mama Phyllis.”

As Burke realized she had no parental rights to Jesse, they launched a campaign for Burke to adopt him. After a long investigation the California Department of Social Services recommended against adoption. “A normal, affectionate, parental relationship is well established between petitioner [Burke] and child. However, the State Department of Social Services does not believe that this adoption is in the best interests of this minor….” At the adoption hearing, however, the judge disagreed and allowed the adoption. “Each respectively shall have all the rights and be subject to all the duties of natural parent and child” (Burke, 1993, p. 229). They became a family. (As of 2003, a number of states allow the non-biological parent of a child in a lesbian or gay family to adopt the child.)

African American Families Returning South

In Call to Home: African Americans Reclaim the Rural South (1996), Carol Stack tells the stories of southern African American families whose members migrated north for work in the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s, but who began to return home in the 1970s. They did so despite the persistent poverty and discrimination in the small southern towns where their families lived.

They came home primarily for family reasons, but also to escape the violence in northern cities. “People feel an obligation to help their kin or even a sense of mission, to redeem a lost community, … ailing grandparents, a dream of running a restaurant, a passion for the land, … homesickness, missionary vision, community redemption, fate, romance, politics, sex, religion” (Stack, 1996, pp, xv, 6).

Pearl and Samuel Bishop’s family is one of the families whose story Stack narrates. Pearl was fourteen and Samuel twenty-two when they married in 1944...