![]()

1

Valuing Public Goods Using the Contingent Valuation Method Contingent

Our national commitment to a cleaner and safer environment has persisted in the face of oil embargos, stagflation, concerns about economic competitiveness, and competing budgetary claims. But as we progress toward the goal of a cleaner environment, each successive improvement becomes more costly to accomplish than its predecessor. Given finite public resources and restless taxpayers, this inevitably raises some difficult policy questions. How clean should we make the air? Should we attempt to make the lower Mississippi River as pure as the lakes in Wisconsin? Just how high a level of impurity should we tolerate in our drinking water? Is a further expansion of a state's park system justified in the face of the legitimate needs of industrial developers? Do we buy another B1 bomber? How much more do Medicare recipients value access to their traditional doctor than being enrolled in a health maintenance organization? Economists believe that questions like these can be addressed with empirical research in the form of benefit-cost analysis. By balancing the costs of public goods against their benefits, decision makers can arrive at more informed choices, or so the logic goes. In recent years the demand for such an accounting has found increasing favor among federal and state policy makers.

Unfortunately, few endeavors are more difficult than assigning a dollar value to something as elusive as increases in air visibility, or keeping the option of paddling a canoe in a wilderness preserve. Economists have long measured the value of goods that are routinely bought and sold in the marketplace. But ordinary markets do not exist for "public" goods such as national defense, the Apollo program to send man to the moon, and many environmental amenities.1 Sometimes, as in the case of recreation sites, this is because under public policy there is no charge for the good or service, or there is an arbitrarily determined charge (which does not reflect the full cost of providing the service or its true market value). In other cases, such as air and water quality improvements, which are public goods in the truest sense of the word, a charge would not be feasible because once the amenities are provided, people cannot be excluded from enjoying them.

For decades economists have grappled with the challenge of valuing public goods. The contingent valuation (CV) method is one of a number of ingenious ways they have developed to accomplish this demanding and important task. For reasons to be presented throughout this book, we argue that as things now stand, contingent valuation represents the most promising approach yet developed for determining the public's willingness to pay for public goods. Generally speaking, it appears as accurate as other available methods, it requires the researcher to make fewer assumptions, and it is capable of measuring types of benefits that other methods can measure only with difficulty, if at all. Our message is one of optimism tempered with realism. Like all sophisticated methodologies, contingent valuation presents challenges, and an important focus of the book is on the pitfalls of using the method. Contingent valuation's use of surveys to obtain consumer responses to hypothetical situations makes it vulnerable to various types of error, which we consider in detail so the researcher can take steps to avoid them and so the policy maker can evaluate and use CV findings with confidence.

The Contingent Valuation Method

The CV method uses survey questions to elicit people's preferences for public goods by finding out what they would be willing to pay for specified improvements in them. The method is thus aimed at eliciting their willingness to pay (WTP) in dollar amounts.2 It circumvents the absence of markets for public goods by presenting consumers with hypothetical markets in which they have the opportunity to buy the good in question. The hypothetical market may be modeled after either a private goods market or a political market. Because the elicited WTP values are contingent upon the particular hypothetical market described to the respondent, this approach came to be called the contingent valuation method (Brookshire and Eubanks, 1978; Brookshire and Randall, 1978; Schulze and d'Arge, 1978).3 Respondents are presented with material, often in the course of a personal interview conducted face to face, which consists of three parts:

- A detailed description of the good(s) being valued and the hypothetical circumstance under which it is made available to the respondent. The researcher constructs a model market in considerable detail, which is communicated to the respondent in the form of a scenario that is read by the interviewer during the course of the interview. The market is designed to be as plausible as possible. It describes the good to be valued, the baseline level of provision, the structure under which the good is to be provided, the range of available substitutes, and the method of payment. In order to trace out a demand curve for the good, respondents are usually asked to value several levels of provision.

- Questions which elicit the respondents' willingness to pay for the good(s) being valued. These questions are designed to facilitate the valuation process without themselves biasing the respondent's WTP amounts.

- Questions about respondents' characteristics (for example, age, income), their preferences relevant to the good(s) being valued, and their use of the good(s). This information, some of which is usually elicited preceding and some following reading of the scenario, is used in regression equations to estimate a valuation function for the good. Successful estimations using variables which theory identifies as predictive of people's willingness to pay are partial evidence for reliability and validity.

If the study is well designed and carefully pretested, the respondents' answers to the valuation questions should represent valid WTP responses. The next step is to use these amounts to develop a benefit estimate. If the sample is meticulously selected by means of random sampling procedures, if the response rate is high enough, and if the appropriate adjustments are made to compensate for participants who fail to respond (nonrespondents) and for those who give "poor"-quality data, the results can be generalized with a known margin of error to the population from which the respondents were sampled. The capability of generalization is a powerful feature of the sample survey method. In this way the responses given by, say, eight hundred people can be used to represent the responses that everyone in a river basin, a state or region of the country, or even the entire country would give if they were all queried.

Illustrative Scenarios

The particular form a CV study takes varies according to the nature of the good being valued, the methodological and theoretical constraints imposed by CV practice, the population being surveyed, and the researcher's imagination and ingenuity. The following brief descriptions of how four CV researchers approached the task of designing their scenarios illustrate this diversity. They offer a glimpse of how researchers have attempted to use the method to measure four different benefits: improvement of visibility impairments affecting a recreational area, improvement of national water quality, reductions of risk from motor vehicle accidents, and the level of services (reductions in services) provided by a local senior citizens' program.

Aesthetic Benefits

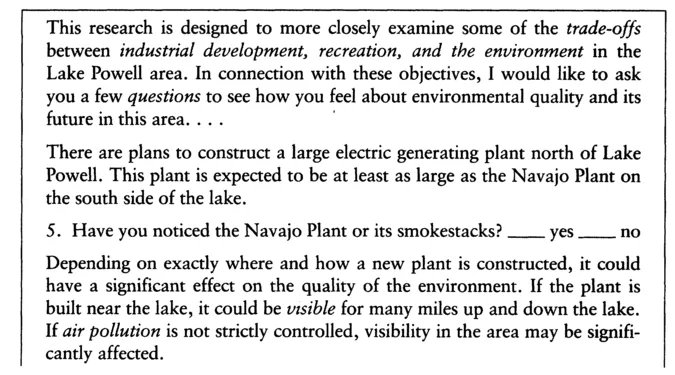

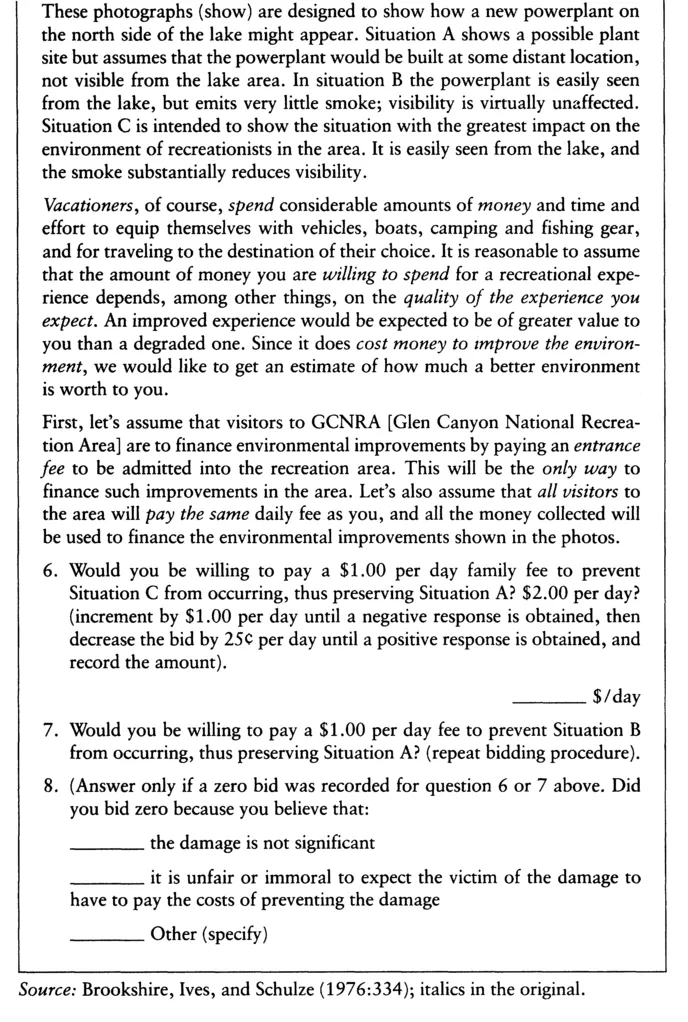

Figure 1-1 contains the scenario which was used in in-person interviews for a study (Brookshire, Ives, and Schulze, 1976) which sought to value

Figure 1-1. Wording of an early contingent vaulation scenario used in the Lake Powell visibility study

the aesthetic impact of a proposed power plant on the north shore of the Lake Powell recreational area in Utah. The amenity the respondents were asked to value was the aesthetic benefit of having their view of Lake Powell unobstructed by the visible presence of a power plant and the smoke from the plant. The researchers used sets of specially created photographs to depict the baseline view and two levels of impairment. Situation A represented the view without the power plant. The photographs for situation B showed only some smoke from the hypothetical power plant, which itself was not in view. The photographs for C showed the plant, in addition to a greater amount of smoke. The respondents were asked to say how much they were willing to pay to preserve situation A, first from the degradation represented in B, then from situation C. The elicitation method used in this study is known as the bidding game, an iterative technique illustrated in question 6 in figure 1-1. The payment vehicle was a hypothetical entrance fee to the recreation area.

National Freshwater Quality

When Congress passed the Clean Water Act of 1972, it mandated the attainment of a national goal to make every freshwater body in the country clean enough to be used for boating, fishing, and swimming. A national water quality study conducted by the present authors used the CV method to measure this program's overall benefits (Mitchell and Carson, 1981, 1984; Carson and Mitchell, 1986) (hereafter referred to as the water quality study; for the survey instrument used in this study, see appendix B). A preliminary study was conducted in 1980 to test a draft instrument and the feasibility of using the CV method in a national survey. In 1984 a revised instrument was administered by professional interviewers to a national sample.

The scenario for the water quality study was much longer than the one used for the Lake Powell study, requiring interviews which lasted an average of 45 minutes. A central design issue was how to describe the amenity to the respondents. The description had to be understandable, so that the respondents could clearly grasp what they were valuing, and policy-relevant, so that the results could be of use to policy makers. The baseline from which the respondents were asked to measure the changes to be valued was described as a minimum level of water quality in the nation's lakes, rivers, and streams—that is, a level below "boatable" quality.4 A total of three improvements in minimum national water quality were valued; from below boatable to the boatable level, from boatable to "fishable," and from fishable to "swimmable" water quality.5 These levels were described in words and shown on a water quality ladder which was used as a key visual aid throughout the scenario. The payment vehicle, annual taxes and higher product prices, was chosen to correspond with the way citizens actually pay for improvements in water quality.

A good example of the kind of methodological problem which a CV study has to overcome was our difficulty in finding an unbiased way to elicit the WTP amounts from the respondents. We initially tried to use a bidding game method similar to the one used in the Lake Powell study, but our preliminary tests found that the initial amount suggested by the interviewer often influenced respondents' answers because they tended to base their answers on this amount instead of making an independent determination of what the water quality improvements were worth to them.6 Our solution to this "starting point bias" was to use a payment card which showed a large number of dollar amounts ranging from $0 to high figures. In order to provide a meaningful context for the valuation exercise, five of these dollar figures (the "benchmarks") were identified as the amounts households in the respondents' income groups were currently paying in taxes and in higher prices for nonenvironmental public goods such as defense and police and fire protection.

The water quality study also illustrates the use of the split-sample (split-ballot) technique to examine the influence of scenario components on the respondents' WTP amounts. This ability to conduct experiments within surveys is regularly exploited by CV researchers for that purpose. If the sample is big enough, survey samples can be divided by a random procedure into equivalent subsamples which value the good under different conditions. In our preliminary 1980 study and a large 1983 pretest, we administered different versions of the payment cards to subsamples to see if the amounts we told respondents they were paying for the other public goods biased the WTP amounts they gave for water quality in some fashion.7

Transportation Safety

Because of the growing need to make choices about which risk reduction programs are the most worthwhile, there is considerable interest in valuing safety improvements. The real-market-based revealed preference techniques (see Blomquist, 1982) attempt to identify and observe choices in situations in which people actually trade off income against physical risk. The limited applicability of this approach to many types of risks led Jones-Lee and his colleagues (Jones-Lee, Hammerton, and Philips, 1985) to attempt to use the CV method to measure the value of risk reductions.8 Their survey consisted of lengthy personal interviews with a sample of people in England, Scotland, and Wales. The centerpiece of the study was a series of questions designed to provide estimates of the sample's willingness to pay for certain types of transportation risk reductions.9

The primary challenge faced by these researchers was to accurately convey risk levels and risk reductions to the respondents. The solution found by Jones-Lee and his colleagues for this "far from straightforward" problem was to describe the risks in verbal terms as probabilities of "x in 100,000," and in visual terms as a piece of graph paper with 100,000 squares, x of which were blacked out. Altogether, they obtained WTP amounts for three different risk change situations. Two of the situations involved hypothetical private markets; the other described a hypothetical public goods market. The following is one of their private good scenarios:

Imagine that you have to make a long coach (bus) trip in a foreign country. You have been given £200 for your travelling expenses, and given the name of a coach service which will take you for exactly £200. The risk of being killed on the journey with this coach firm is 8 in 100,000. You can choose to travel with a safer coach service if you want to, but the fare will be higher, and you will have to pay the extra cost yourself.

- How much extra, if anything, would you be prepared to pay to use a coach service with a risk of being killed of 4 in 100,000—that is half the risk of the one at £200?

- How much extra, if anything, would you be prepared to pay to use a coach service with a risk of being killed of 1 in 100,000—one eighth the risk of the one at £200? (Jones-Lee, Hammerton, and Philips, 1985:56)

The researchers used still another type of elicitation method in their study. All respondents were ask...