![]()

CHAPTER 1

Business Liability

Liability does apply with respect to the amount of the oil spill.

—Ken Salazar, U.S. Secretary of the Interior,

addressing the Gulf Oil Spill in 2010

Learning Objectives

- 1.Describe the concept and scope of business liability.

- 2.Summarize the effects of insurance and business organization on liability.

- 3.Explain the role of courts, mediation, and arbitration in addressing liability claims.

What Is Business Liability?

For business owners, opportunities to sell goods and services are exciting. But revenue and profit usually require significant resources, and many businesses incur liabilities—debts or other obligations owed to others—along the way. Liability includes loans borrowed to finance the business and other obligations spelled out in business contracts. If a business fails to meet its contractual obligations, a liability remains and those owed will seek compensation so long as it remains profitable to do so.

Sometimes the consequences of business liability are easy to predict and plan for; other times not. For a business loan backed by equity in the business, the lender goes after the equity if the loan goes unpaid—a predictable outcome. Actual debt recovery may take considerable time and expense, but this contingency is relatively easy to plan for. Many other standard business contracts entail liabilities that are fairly easy to foresee, but not all. Furthermore, the scope of business liability extends beyond contracts, and the great reach of potential liability makes it even harder to foresee. This book focuses on business liabilities whose consequences are relatively hard to predict, but can nevertheless be identified and prepared for in some way.

Business liability comes from many directions, so many that a detailed account of all possibilities is impossible. A business cannot foresee every form of liability, but its managers and owners should develop an intuitive understanding of liability by considering the business’s relationships with society. It is not just desired relationships that might be listed in a business plan, but actual ones.

To get a grip on the real scope of business liability, you have to think big, have a big picture in mind, a big idea. One big idea discussed in this book is the social contract. For a business owner or manager who wants to avoid a business liability mistake, it is useful to take the view that businesses have liability because they are bound by a social contract to avoid certain harms to others. The social contract does not take the form of a tidy 5-page or 10-page document that a business signs and sends to the government. It does not necessarily stay the same over time, and may or may not ultimately be fair. It does reflect and signify the body of laws and regulations that a business faces and is colored by the economic, social, and political institutions of the day. A social contract can serve as a theme or umbrella for myriad elements of business liability—and so can serve as a conceptual model to simplify some aspects of liability faced by business owners and managers. As a practical matter, for the purposes of this book a social contract is an idea or framework that serves to define and limit the rights and responsibilities of society’s members.

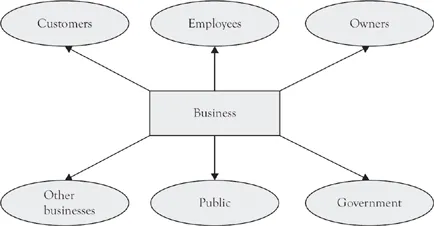

The scope of possible liabilities that a typical business faces is mind-boggling. It is key to have some hunch, or intuition, about where liability comes from and the impact it has on businesses. A good hunch about business liability can be formed by thinking about how a business stands in social contract with others. Each business has some implicit social contract with society, with liability for its actions (or inactions) that cause harm or loss to others. Relationships between a business and society are always sources of liability, as shown in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Sources of business liability

In the United States, a social contract is partly framed by the U.S. Constitution and its amendments, as well as other laws introduced by the federal government and upheld by the courts, treaties and agreements with other nations, the laws of state and local governments, and the opinions of the court on cases tried before it. Each of these foundational elements may create rights and duties that collectively frame the social contract. A business that breaches the contract causes a loss to society, a liability.

The American social contract, as a catchall for the various rights and responsibilities we bear to one another, is formidable and far-reaching. Our system of justice, our rule of law, acts to right imbalances and provide opportunity for wrongs to be righted. America’s legal system supports the social contract—or rather the rights and responsibilities it is intended to signify—with remarkable commitment and vigilance, despite the system’s imperfections. The same is not true in all countries. In the Philippines, a country in southeast Asia, I spent a year in high school in the 1980s and lived with a host family. My host father was a trained lawyer, but could not find work because the legal system had become weak and lawyers were of little use, so he ran a convenience store instead at the University of the Philippines. Matters have improved greatly since that time, but weak legal institutions and corruption continue to be problems for law in the developing world. In many countries, a business can bribe its way out of many obligations to society. In America the bribe is less reliable, in part because government officials are better paid and so less benefitted by bribes economically and also because a centuries-old tradition of government propriety still carries momentum—despite many lapses.

For a business manager pondering the scope of the company’s liability, it is useful to develop an intuitive and informed sense of what is owed to society, as if the company were bound by a social contract that could be spelled out, at least in principle. This sense of obligation does not require a knowledge of all U.S. laws—not even lawyers or judges have that. The relevant social contract includes a set of rights and limitations on behavior that protect people from harm, and a basic understanding of the legal scope of harm is a must. As noted in the Preface, the book you are reading is no form of legal advice, but the economics of business liability and damages is framed by the legal system, so a discussion of the legal landscape is inevitable.

A good starting point for assessing business liability is to briefly detail the six relationships shown in Figure 1.1. Loans and other business contracts create business-to-business liability, but each business has customers and—like it or not—potential liability in their customer relationships. Employees are owed paychecks but also owed fair and respectful treatment, a form of liability shaped by the social contract between the employer and the employee. For businesses big enough so that their actions are not one and the same as that of their owners, business owes its owners, and so is liable to them. All businesses know about taxes—one sort of debt owed to the government, and some end up with other ties to assets that lie in the government’s reach, and so more liability. Furthermore, general members of the public hold a potential relationship with a given business, by sharing the same road space on a given day, the same communication network, water supply, or other component of our common space. All of these relationships carry potential liability.

To illustrate, consider my business activity as the author of this book. I get paid royalties by my publisher, to whom I have sold the rights to this book. The publisher is my customer and our contract spells out my obligations, including publication deadlines, quality guidelines, and book length. I have no ghostwriter or other employees, nor other business owners, so no liability there. I do have liability to other businesses, as I am a university professor and my book counts as a scholarly contribution that my university takes credit for supporting. Shared credit implies some liability on my part to ensure quality and protect the university’s reputation. This book deal on my part is straightforward tax wise, and my liability to the government is otherwise transparent.

Where do you, dear reader, fit into my liability as book author? You are part of the public at large. I am obliged to avoid having boxes of my books fallout of the trunk of my car and smack your car’s fender on the roadway. The publisher owns the words you are reading, but I profit from book sales. Do I not also bear obligation to the reader, for the book itself? That is the hardest part of my liability puzzle. I have designed the book to improve your understanding of business liability and economic damages, with no intent to harm anyone. It is advertised as a book of ideas, not advice, so cannot be said to poorly advise. This book contains examples but omits names and identifying details of real people, so it cannot wrongly characterize anyone in the general public. For these reasons my legal duty to you is pretty limited.

Insurance

In this book we will be talking mostly about business liabilities that are hard to anticipate; for example, product defects, which unlike debts and interest payments, are hard to predict.

To deal with unexpected liabilities, an elegant solution is insurance—a contract in which one party meets the obligations of another, under specific conditions. Pay a premium and the nightmare of ruinous mistaken harm vanishes. Indeed, insurance markets have made possible much business activity that could not otherwise take place. But the insurance company is not your friend. It plays a risk game that it wins on average, but you are a risk, not a business partner.

Insurance makes the social contract more workable by lessening the burden on courts to enforce the contract’s obligations. Insurance companies can quickly assess damages and provide remedies, but courts cannot. Insurance works so well that it has been assigned a special place in the social contract, an institutional role alongside the courts. All drivers must buy automobile liability insurance; many businesses must buy workman’s compensation insurance, which presupposes the existence of insurance markets. Additionally, the government provides insurance to cover unemployment and disruptions in the market for insurance itself, such as insurance company bankruptcy.

Insurance is good, but insurance markets are like casinos. The insurer’s pursuit of profit is good for the social contract and business, but insurers know the contract better than most of their customers do. Big insurance companies have armies of lawyers. They know today’s law and anticipate its changes tomorrow.

Insurance companies cover some business liabilities, but not all. The insurance agent will sit down with a business owner and discuss a range of liabilities, touching on some or all of the points shown in Figure 1.1. But liability is a thing to be identified by the business itself, preferably with a lawyer’s input, before any meetings with insurance agents. Insurance helps to mitigate the business’s risk of liability, but insurers lack the exhaustive knowledge of any specific business that would be needed to fully address this risk. Mitigation is not absolution. The liability buck never gets fully passed from business to its insurer.

Businesses look to their insurance policies for peace of mind, but the insurer sees them as loaded guns. Every policy is written to cover some stated form of liability, but is otherwise designed to minimize liability’s scope. This scope is whittled down until it just meets the demands of the social contract. Anything extra would present more risk for the insurer, and less profit.

When a business causes harm, society comes after it and not after its insurer. I illustrate this in Figure 1.2. Business has an obligation to society, and its insurer has an obligation to the insurer. It is easy to suppose instead that the insurer assumes the business’s obligation. For example, in routine car accidents a claim is usually made against a driver...