![]()

Chapter 1

THE NATURE OF COGNITION

This book is intended to describe the subject of cognition; but since “cognition” is the name given to the whole of the foundations of normal human behaviour, it will be necessary to limit the breadth of the investigation.

In the first place, it is not intended to discuss animal cognition as such, although so much of the theory of cognition is based upon animal experiments, that examples drawn from work on animals will often be used, and some aspects of ethology will be discussed (Chapter 11). Secondly, we shall not be concerned with clinical or abnormal psychology, except in so far that discoveries in these fields have a suggestive value for those interested in normal cognition. Paranormal cognition, which is the technical name for work on telepathic and other obscure, but possible, forms of communication, is also quite outside the scope of the present book.

It would be nice to be able to add that the philosophy and physiology of cognition are also irrelevant, but they are not. A chapter (Chapter 7) is devoted to cognition and philosophy, and other references will certainly be made to the approach of philosophers and physiologists to our common interest, for their work is in some ways very close to that of the psychologist; but to enlarge on the detail of philosophical and physiological matters alone would involve far more space than the present volume affords.

By cognition, we shall mean the way human beings perceive and learn, how they reason and think, even how they remember and imagine; and how their “minds” work in the ordinary day-to-day activities of life. This means that we want to know how they learn a poem, or a part in a play; how they remember what they have learnt; how they perceive the relations and layout of a map, a scene, or a painting; how they recall certain events in their pasts, and how they imagine things that may never have occurred, or at least, things that they themselves did not see.

Perception may perhaps be usefully thought of as being connected with our input of information. “Perception” refers, of course, to all the special senses, but the eyes have been most extensively studied. Now we know only too well that we may be wrong about just what is happening around us. To use a simple example: we may be led into saying that we saw three men walking down the road, whereas actually there were two men and a woman. Often the difficulty is that we cannot stop our minds (or brains) from making inferences all the time about what the eyes see (even unconscious inferences), and this leads to many errors. Making unwarranted assumptions, taking things for granted, jumping to conclusions, all these affect our perceptual efficiency.

This, so far, seems reasonable enough, but we must recognize that there may be many complications. We shall find that we have to dwell upon our own actions, and take care to be aware of what we are doing: this is the process called “introspection” or, when it involves much that is in the past, “retrospection”.

Now most of us discover, rather to our surprise, that we are not very good at introspection. People often find that they are unaware, consciously, of many things that seem to have influenced their actions. They may solve problems of a logical kind, but be quite unable to say what steps they took to reach their solutions. It is not only that they cannot remember things well enough, but that, even while they are actually cogitating on a problem, they find it difficult to say exactly what it is they are doing. It is a well-known and well-validated fact that one may go to bed with an unsolved problem on the mind, and wake to find it solved. This seems to show that the cognitive operations do not stop during sleep, but we must be careful on this point, since many psychologists have defined cognition as that part of perceiving, learning and thinking that is conscious.

These problems become more complicated when we consider the findings of Sigmund Freud; in particular, that unconscious motives apparently influence the behaviour of man. Everyone has motives or reasons for learning things, and it is a reasonable guess that these motives are closely connected with the foundations of human survival. At the same time, answers to questions about our motives would need to be somewhat more mundane, in that we are usually asking about what immediately influenced our behaviour, and not about what is the ultimate driving force. In any case we surely cannot say what our unconscious motives are by introspection.

Our main difficulty here is that cognition could be regarded as referring to the unconscious processes as well as to the conscious; but if this is agreed, then we are going to be using the words “learning”, “perceiving”, “thinking”, and the other cognitive terms, in rather a special and unusual way. This way is sometimes called “behaviouristic”.

This last point raises a special problem of science: that of definitions. We must be prepared to say, and in a fairly definite and clear way, what it is that we are talking about, because many of the most important terms of ordinary, everyday language are ambiguous, and may mean many different things according to the context in which they are used; they have all sorts of shades of different meaning. This question we shall postpone till the next chapter, since defining terms can be a rather tiresome business – tiresome, but necessary, even if we still cannot make the definitions as precise as we should like.

Apart from the fact that the science of cognition must be in accord with common sense, and follow step by step in a clear, logical argument, the language used must be precise enough to allow experiments to be carried out in order to confirm the truth, or otherwise, of our cognitive theories. These are all points at which philosophy touches cognition.

To illustrate the relation between psychology and the biological sciences, it is convenient to think of a motor-car. If we merely observe its outward characteristics, check its speed and acceleration, and the action of the gears and brakes, then we are what we might facetiously call “car psychologists”. But if we open the bonnet and take up the floorboards, investigate the carburettor and ignition system, take the engine to pieces, and so on, then we are, by the same analogy, in the domain of “car physiology”. Mainly, this book is about the psychology of cognition – human cognition.

Out of these problems, dealt with in many ways over several hundreds of years, has emerged the method of psychological approach called “behaviourism”; this is the method of studying the human being objectively, and not relying on introspective evidence, at least, not directly. We must now trace out some of the main historical developments which brought about the present state of affairs.

Cognition and early Experimental Psychology

Psychology began to emerge as a scientific discipline slightly over a hundred years ago, and it has been evolving more and more as a separate discipline ever since. At the same time there has been an increasing awareness that it is only artificially separated from philosophy and sociology, as well as the biological sciences generally, and even the physical sciences.

This may appear to be something of a paradox, but it is a peculiar fact that, while sciences have become increasingly specialized and compartmentalized, there have been – perhaps for this very reason – movements to unify it; and there have been claims that science really represents a homogeneous mass of well-validated information.

The background of psychology is in philosophy, biology and, as far as method is concerned, physics. It is almost as if scientists had said that the methods of science, having worked so well in dealing with the physical world, could now be applied to the mental world.

Herbart’s Textbook of Psychology appeared in 1816, heralding the subject in its slender beginnings, but it was not until the work of Fechner, Helmholtz and Wundt, among many others, that the beginnings of the use of experimental methods could be seen.

Kant influenced the development of psychology, and was one of the first people to distinguish cognitive, or reasonable, from conative, or emotional, activities. After Kant, other philosophers – notably Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill – continued the development of psychological theories, though without using experimental methods.

The early work of Fechner, Muller and Weber, as well as Helmholtz and Wundt, was in experimentation on sensation and perception, especially hearing and vision. One well-known outcome of this was the famous Fechner-Weber law, which said that, “in observing the difference of two magnitudes, what we perceive is the ratio of the difference to the magnitudes compared”. Even now this law is thought to hold over the bulk of the range of normal sensory stimulation.

While these early beginnings were occurring, physiology had been developing in such a manner as to facilitate its inevitable link-up with behaviour.

The Bell-Magendie law, as it is sometimes called, named after the two physiologists who first propounded it, made the distinction which is now widely accepted between sensory and motor nerves. This anatomical distinction is between nerves running into the nerve pathways of the spinal cord, and carrying incoming messages from the various specialized receptors in the skin, and the outgoing nerves which carry messages to the output organs such as the muscles of the arms and legs. This is closely connected with our distinction between sensory and motor activity; the stimuli are sensory and the responses are motor.

Helmholtz, although perhaps primarily famous as a physicist, was also an eminent physiologist, and was one of the founders of what we tend, now, to call physiological psychology. His work in the latter field is closely connected with colour vision and hearing. Indeed, his theories in both these domains are now regarded as essentially correct, although they have naturally been considerably elaborated since the time of his original work. He is also especially well known for his theory of unconscious inference.

Helmholtz’s theory of unconscious inference has been used to explain the constancy effect that occurs in our perception of colours and shapes. We shall discuss this in Chapter 8, but it can be said now that Helmholtz adopted a characteristically empirical attitude in accounting for our ability to recognize coal as black even when seen in a very bright light. Helmholtz suggested that we remembered the real colour of coal (“real” here means its colour in white light) and made allowances for the illuminating conditions which changed its immediate appearance. The use of the memory in interpreting may not, of course, be a process of which we are conscious.

This empiricist interpretation of constancy was opposed by Hering, who suggested that the effect was due to the functioning of our peripheral visual system in the retina. This alternative view is sometimes called “Nativist”, and the two views are collectively referred to as the “Nativist-Empiricist Controversy” – a dispute which is still not finally settled.

Another noteworthy milestone in the development of early experimental psychology was the work by Flourens on localization of function in the highest level of the brain: the cerebral cortex. Flourens’ work, published in 1824 and 1825, was primarily based upon the removal of different areas of the brain, especially in the cerebral cortex. He found that relatively definite functions were affected by such removal. Perhaps the most significant of all his discoveries was that, with suitably chosen destruction of the nervous system, the subjects appeared to retain sensations in their eyes, and in the special senses generally, but lost the ability to make perceptions, i.e. to co-ordinate and utilize the information that was still being recorded by those special senses.

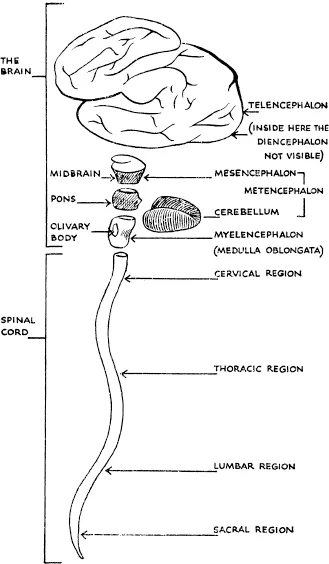

FIG. 1. THE BRAIN AND THE NERVOUS SYSTEM

A diagrammatic representation of the brain and the nervous system, showing the main parts which are separated for convenience of illustration. The Telencephalon includes the cerebral cortex, and the Diencephalon includes the thalamus and hypothalamus.

Even more important than this, Flourens showed that a large part of the brain, called the cerebellum, was concerned with motor coordination, a finding which modern neurophysiologists nave been able to confirm (injuries to the human cerebellum certainly interfere with the ability to co-ordinate muscular movements). The same techniques gave hints as to the function of other brain areas, and supported the doctrine of functional localization in the brain, although Flourens himself gave a somewhat different interpretation. The view that the cerebral cortex is localized in its function is still widely accepted, but with some modifications and reservations.

Of the many famous physiologists who have influenced our views on the relation between behaviour and the function of the nervous system, none has had a greater influence than Sir Charles Sherrington, who was able to develop a more complete picture of the nervous system and its function than anyone previously. He found that the cerebral cortex itself seemed to have an inhibiting effect upon some of the lower levels of the central nervous system and, indeed, that the idea of such levels, which was developed by Hughlings Jackson and Flourens, was consistent with the experimental evidence available.

From Sherrington’s work we have acquired the concept of inhibition. This is, essentially, an antagonism to excitation which takes place when a particular nerve or set of nerves is stimulated. The stimulated nerves connect with other nerves at the synapses, and these (the second) sets of nerves ramify to make a sort of network throughout the body. The synapses are the controlling centres as far as the distribution of local nervous activity is concerned, and they can be either in an excitatory or an inhibitory state, i.e. the state of the synapse decides whether, when an impulse arrives, it will pass through and fire the next nerve in the chain or not. The complicated co-ordination of this process leads eventually to nerves firing (or not firing) particular muscles, and thus activating bodily movements. This whole process is now thought to be under cerebral cortical control.

By removal of the higher levels of the nervous system – the cerebral cortex at the top, the basal ganglia beneath it, then the thalamus, hypothalamus, pons and medulla (see Figure 1), we can gradually reduce the animal to a spinal animal (i.e. having only the spinal cord intact), from which simple responses can yet be elicited. The seresponses were analysed in great detail by Sherrington and his many followers, and are still being analysed right up to the present day.

We shall have more to say later about Sherrington’s theory of nervous activity and its relation to cognition, and we should note that it represents perhaps the greatest single contribution to our present knowledge, although naturally it too is being modified as a result of a steady influx of knowledge.

In the meantime, and rather before Sherrington, we have the development by Fechner of psycho-physics, the first systematic attempt to measure sensation by appeal to strength and conditions of stimulation. This body of methods is closely bound up with the history of experimental psychology.

The psycho-physical methods will be discussed in Chapter 8, but we can say now that their importance lies in the fact that they represent a first attempt to link the objective, or publicly observable, world with the subjective, or private, world of our own feelings. Such a link is clearly necessary to allow the direct application of measurement to our subjective behaviour.

Perhaps even more directly relevant to cognition was the early work on thinking by Kulpe and the Wurzburg school of psychologists. This school was concerned – in rough distinction from the experimental work of Wundt, Fechner and others – with systematic introspection. The operations of judgment, feeling, association and will were all studied. An analysis was made of thinking, and although a great deal was learnt about our higher mental processes, it was often of a negative character, showing the limited usefulness of introspection as a source of information about the internal processes of thought, such as may be involved in finding the solutions to particular problems.

It should be understood that we have selected from the full breadth and depth of psychology, or cognition, but a few of the milestones in the last hundred years of its development, taking those especially which have led to the recent development of “schools” of psychology. These schools are now being replaced by one or two principal integrated theories, the discussion of which will be one of the main themes of this book.

Many of the schools were working on problems which seemed, to those concerned at that time, to differ radically one from another, and so appeared to be less comparable than they do now, from the present historical standpoint. Their differences, indeed, are now seen to have been more imaginary than real.

Psycho-analysis, under Freud, is widely known for its clinical interpretations of abnormal behaviour and its t...