eBook - ePub

Health Psychology

Anthony Curtis

This is a test

Share book

- 190 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Health Psychology

Anthony Curtis

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This simple and concise introduction to the psychology of health is the perfect text for students new to the area. Topics covered include health policy and epidemiology, genetic factors in disease, the experience of illness as a patient, beliefs and attitudes, stress, pain and healthy lifestyles.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Health Psychology an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Health Psychology by Anthony Curtis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction to Health Psychology

Defining health psychology

Historical perspective on health and illness

The biomedical model

The biopsychosocial model

Psychology and health

Models of behaviour change

Summary

Welcome to the fascinating area of health psychology! This text aims to provide an insight into the many fields that make up health psychology. You may be a student, nurse or other practitioner in the health field, or just seeking to find out more about your health and the role that psychology can play in understanding health states and health status. I hope that this book is of interest to you and relevant to your needs.

Defining Health Psychology

In trying to define health psychology, one must first try and define what is meant by ‘health’ as a concept. The most commonly quoted definition of health is provided in the Constitution of the World Health Organization (WHO, 1946):

Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being, and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.

This definition is considered to have positive and negative attributes by Downie et al. (1996). In the first part of the definition, they argue that health is seen in positive terms (i.e. the presence of a positive quality: well-being). In the second part of the definition, health is viewed (in a negative sense) as involving the absence of disease or infirmity (themselves negative in connotation). Taken together, the definition implies that true health involves both a prevention of ill-health (e.g. disease, injury, illness) and the promotion of positive health, the latter of which has been largely neglected.

Banyard (1996) has criticised the above definition on the grounds that a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being is very difficult to achieve in reality and that the definition ignores wider social, political and economic factors which may contribute to this state. It further implies that people who are not fulfilled are also not healthy!

Historical Perspective on Health and Illness

From the seventeenth century to the beginning of the twentieth century, most people in Western society considered that ill-health was something that just ‘happened to someone’ and that there was very little that could be done in terms of protecting against it. Once they were ill, it was argued, people simply expected to seek medical care in order to be cured. Unfortunately, medicine was not always able to help them. In fact, the leading causes of death during this period were the acute (i.e. sudden-onset) infectious diseases such as influenza, pneumonia and tuberculosis. Once contracted, the duration of such illnesses was relatively short: a person either died or got well within a matter of weeks. People also felt little responsibility for contracting these illnesses because they believed that it was impossible to avoid them. Some believed that their illness was the work of evil forces or divine intervention.

Today, the major causes of disease and illness are very different. They are the chronic (i.e. slow-onset, long-term) ‘diseases of living’, especially heart disease, cancer and diabetes. These are the main contributors to disability and death and usually cannot be ‘cured’ (unlike the traditional infectious diseases) but rather must be managed by patients and their doctors. This dramatic shift in the causes (and consequences) of illness, disease and mortality reflects not only our increased understanding of medicine but also demands new methods of treatment. Also, as patterns of illness have changed over time, so has our need for new models of health.

The generally held view is that, with rapid developments in medical technology and interventions, infectious diseases such as tuberculosis, measles and chicken pox have dramatically declined as a consequence of the introduction of chemotherapy and vaccinations. Similarly, the use of antibiotics was believed to be responsible for the dramatic decline in the incidence and prevalence of pneumonia and flu. There appears therefore to be a clear relationship between a specific pathogen (disease-causing organism) and a physical illness. This is the view held by the biomedical model which has dominated medicine and health psychology until recently.

The Biomedical Model

The biomedical model (or ‘medical model’ as it is also known) takes the view that there are known and knowable physical causes for disorders. Specifically, germs, genes and chemicals may all contribute in different ways to the causes of disorders. Subsequent treatments are usually also based on physical interventions (e.g. medicines, surgery, etc.). The roots of this approach date back to the seventeenth century and Cartesian dualism, when Western science made a clear distinction between mind and body. The famous French philosopher René Descartes proposed that mind and body are separate entities, rather like a ghost and a biological machine. Different versions of dualism since Descartes have sought to explain the relationship between mind and body, some seeing one as influencing the other and vice versa. According to Descartes, the seat of the soul was in the pineal gland located in the brain and he also believed that animals did not possess such a soul. Modern Western medicine, however, is not dualist and instead is firmly rooted in a monist (materialist) philosophy.

Historically, philosophers have vacillated between the view that the mind and the body are part of the same system and the idea that they are two separate ones. The Greeks developed a humoral theory of illness that was first proposed by Hippocrates in the fourth century BC and expanded by Galen over 500 years later. According to the Greeks, disease arises when the four creating fluids of the body (blood, black bile, yellow bile and phlegm) are out of balance. Treatment involved restoring this balance among the humours and a predominance of one humour was associated with specific bodily temperaments. The important notion here is that disease states were linked to bodily factors (i.e. the later medical model) although these factors could also influence the mind (i.e. the later biopsychosocial model). The Middle Ages saw a swing back to mental explanations of illness (e.g. mysticism and demonology dominated concepts of disease) and this was seen as God’s punishment for wrongdoing. Cure or relief was sought through driving out the evil by torturing the body. Penance and good works thankfully replaced this ‘therapy’! Even today, the links between mind and body, and between religion and healing, remain very close.

Evaluation of the Biomedical Model

- This approach has been criticised for being reductionist in approach (e.g. reducing explanations of illness to explanations involving germs, genes and/or chemicals when wider social and economic factors may also be responsible). One of the main features of holistic medicine is to consider the whole person in treatment and not simply the diseased part of their body.

- Another criticism of the biomedical model is that it often assumes physical causes for disorders. Many ‘modern’ disorders described above (e.g. heart disease, cancer, diabetes, etc.) are considered to be ‘multi-factorial’ disorders; that is, they have many potential causes which may often interact with one another. For example, heart disease may be a product of genetic factors, diet and lifestyle/ behaviour factors, each playing a role in terms of susceptibility to illness, management and treatment success. We have at last acknowledged that humans are not simply machines operating in a social and economic vacuum but rather we are dynamic individuals with many thoughts, feelings and emotions. The extent to which these are merely activities of the brain is still heavily debated.

- Finally, the biomedical model is criticised for placing too much emphasis on ‘body’ at the expense of ‘mind’ as distinguished above. The problem here is that a growing body of research evidence, and indeed our own experiences of health and illness, suggests that our mind influences our body and vice versa. We constantly read of a cancer patient’s ‘will’ in managing cancer and the role of cognitive-behaviour therapy in treating a whole range of disorders. Although the mechanisms linking mind and body are not well understood, many health professionals now believe there is a link and that the absence of evidence should not be taken as evidence of absence.

The Biopsychosocial Model

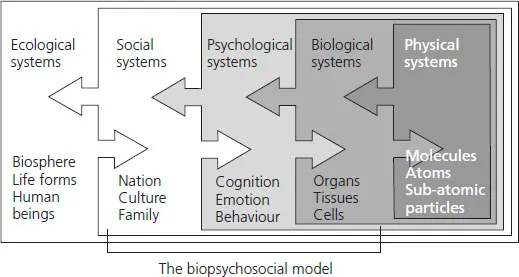

During the last quarter of the twentieth century, physicians, psychologists and medical sociologists have seriously questioned the usefulness of the medical model in explaining health and illness. The biopsychosocial model (see Figure 1.1) is based on a systems approach. At one end of this scale, as Banyard (1996) states, we exist within an ecological system that includes the planet we live on, the life we have developed from and the species we are part of. At the other end of the scale, we are made up of the basic units of the universe (molecules, atoms, etc.). There are no single causes in explaining phenomena here. Instead, many factors influence each other on different levels.

Figure 1.1 The Biopsychosocial Model

Source: Originally titled ‘Systems’ in P. Banyard (1996, p. 6) with permission from Hodder & Stoughton Educational.

In applying this model to health psychology, there has been an increasing need to recognise these additional and wider factors that may affect our health. Engel (1977) proposed a biopsychosocial model of health, which considered that a person’s health was the result of an interaction of biological (i.e. biomedical), psychological and social factors. In other words, biological factors (e.g. viruses, bacteria and lesions) interact with psychological factors (e.g. attitudes, beliefs, behaviours) and social factors (e.g. class, employment, ethnicity) to determine one’s health (see Chapter 2). Similarly, psychological interventions have been effective in the treatment of pain (Chapter 4); cancer, coronary heart disease (CHD) and HIV/AIDS (Chapter 6); and stress (Chapter 8).

Progress Exercise

Think back to the last time that you were unwell or ill. Can you think of biological, psychological and social factors that may have contributed to this? List them in a table using these three categories:

Biological factors | Psychological factors | Social factors |

Social and Environmental Factors

We have now widened up the topic of health and illness to consider other factors that affect our health status. The view that social and environmental factors impact on our health was also supported by Thomas McKeown (1979) in his book The Role of Medicine. McKeown examined the impact of medicine on health from the seventeenth century onwards and found, quite remarkably, that the reduction in infectious diseases such as tuberculosis, pneumonia and influenza was already under way before the development of medical interventions. Further, he argued that these reductions would have taken place anyway because of improvements in social and environmental factors. He argued that:

The influences which led to [the] predominance [of infectious diseases] from the time of the first agricultural revolution 10,000 years ago were insufficient food, environmental hazards and excessive numbers and the measures which led to their decline from the time of the modern Agricultural and Industrial revolutions were predictably improved nutrition, better hygiene and contraception.

(McKeown, 1979, p. 17, cited in Ogden, 1...