Chapter 1 Studying and Practicing Intercultural Communication

Kathryn Sorrells

Sachi Sekimoto

Gordon Nakagawa

The study and practice of intercultural communication in the context of globalization is complex, contested, and often contradictory. Thus, as students and practitioners of intercultural communication, it is important to develop conceptual models, practical skills, and effective strategies to grapple with and make sense of the multifaceted challenges and opportunities that confront us in the global age.

Understanding how cultures differ from each other in terms of values, norms, histories, and worldviews is central to the study of intercultural communication. Equally critical is an awareness of how cultural differences coexist, collide, and are contested within relationships of power. Culture, cultural differences, and the field of intercultural communication, itself, are understood and constructed within contexts of power—historical, political, economic, and social relations of power—that tend to normalize certain perspectives, histories, values, and norms, and devalue as “strange” and “other” those beliefs, practices, knowledges, and points of view that veer from or challenge dominant views.

Guided by the intercultural praxis model, the entries in this chapter illustrate the central roles power and history play in our understanding of culture, cultural differences, and the construction of knowledge. The case study by Kathryn Sorrells and Sachi Sekimoto offers a critical perspective on the history and future trajectories of the intercultural communication field, highlighting moments of contestation and rupture that challenge dominant paradigms and create alternative approaches. Gordon Nakagawa’s poetic personal narrative illustrates how his experience of negotiating racial and cultural identities—the ways he has been targeted by and complicit with stereotypical representations—has led to a sense of agency and responsibility to engage everyday events and interactions as opportunities for social justice. Both entries offer insight into critical forms of analysis, reflection, and action that can create a more socially just and humane world.

Globalizing Intercultural Communication: Traces and Trajectories

Kathryn Sorrells

California State University, Northridge

Sachi Sekimoto

Minnesota State University, Mankato

People from different cultures have come in contact and communicated with one another for many millennia. The Silk Road, for example, was a cultural exchange and trade route that covered more than 4,000 miles from China to Europe and extended westward during the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE) for military and administrative purposes. Aiding political, economic, and cultural interchange, the Silk Road played a central role in the development of European, Chinese, Persian, Arabian, and Indian civilizations (Elisseeff, 2000). In another instance, from the 9th century to the 12th century, ancestors of the Pueblo and Hopi people inhabited Chaco Canyon in northwest New Mexico—a ceremonial, economic, and cultural center for indigenous peoples from distant regions who gathered periodically in the canyon. In its time, Chaco Canyon was an intercultural university and cross-cultural marketplace where ideas, technologies, beliefs, and practices were shared and exchanged (Frazier, 2005).

During the colonial period from the 16th to 20th century, intercultural exchange occurred on a worldwide scale. Sea and land routes brought people, goods, ideas, and beliefs into contact with one another in unprecedented ways. As with the Silk Road and Chaco Canyon, the exchange was not always positive. Much of the intercultural encounter during the colonial period was framed by conquest, religious decree (the Papal Bull issued in 1493), and imperial power justifying the subjugation of people, destruction of cultures, and extraction of wealth from much of the world. The contours of our current era of globalization are shaped by the worldviews and relationships of power forged during the European colonial period.

Today, we inhabit worlds that are far more complex, interconnected, and paradoxical than ever before. Thousands of Silk Roads, both real and virtual, wrap the globe; yet cultural, ethnic, racial, religious, national, and class differences segregate and isolate us. Myriad centers of intercultural exchange like Chaco Canyon bring people into proximity with one another in physical and cyberspace more rapidly and frequently than ever before; yet we tend, often, to gravitate toward what is similar, known, and familiar, minimizing or excluding those who are different. Through scientific and technological advances, we have the capacity to feed all the people of the world; yet 1 in 8 people (870 million of the 7.1 billion world population in 2012) suffer from chronic undernourishment (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2012). Food deserts, where nutritious food is beyond the reach or budget of average consumers, disproportionately affect low-income people and communities of color in the United States (Winn, 2008).

Communication among diverse groups—intercultural communication—has been occurring, as the examples above suggest, for many millennia. Motivated by commerce, conquest, conversion, and community, intercultural interaction can produce innovation and growth as well as exploitation and destruction. The challenges and possibilities of the complicated, increasingly interconnected and inequitable world we live in call out for intercultural communication and exchange. Any one cultural group’s knowledge is partial. We need the varied approaches, alternative perspectives, and unique wisdom that all cultural groups bring—because of their differences, not in spite of them. Understanding the dynamics of intercultural communication is critical for the survival and actualization of humanity in the 21st century.

In this essay, we use the model of intercultural praxis (Sorrells, 2013; Sorrells & Nakagawa, 2008) to critically reflect on significant historical moments in the development of the intercultural communication field. The intercultural praxis model is used to guide our metatheoretical analysis, which reveals the politics of knowledge inherent in the production of disciplinary narratives and explicates our approach to globalizing intercultural communication. As we reflect on the history of the field, we also describe three major paradigms that characterize scholarship in intercultural communication, as well as point to recent scholarly trends. We conclude the essay by sketching out future trajectories impacting students, teachers, and practitioners of intercultural communication.

Historicizing the Field Through Intercultural Praxis

As the title of this reader indicates, we—the editors and contributors of the book—are committed to “globalizing” the way we engage in intercultural communication in everyday practice and as a scholarly pursuit (Sorrells, 2010). The phrase “globalizing intercultural communication” is used here to draw attention to the opportunities and challenges of intercultural communication in an increasingly complex, interconnected, contested, and inequitable world shaped by advanced technologies, global capitalism, and neoliberal policies. Rather than normalizing hegemonic assumptions of neoliberal globalization, “globalizing intercultural communication” means we examine intercultural communication within the context of historical and contemporary relations of power, highlight linkages between the local and global, and uplift critical social justice approaches. To move forward toward the future, however, we must first reflect on how we, as an academic field, have come to be where we are today.

In this section, we use the model of intercultural praxis to examine key historical developments in the field of intercultural communication. The intercultural praxis model provides an analytical framework and epistemological lens that both illuminates and complicates our ways of thinking about the historical development of the academic field. The purpose is not to provide the overarching history of the field but to use the intercultural praxis model to reflect on the politics of knowledge inherent in the formation of an academic field. Thus, our goal is to demonstrate a process of engaging in critical praxis for global consciousness as we trace and reflect on the historical development and theoretical foundations of the field.

What Is Intercultural Praxis?

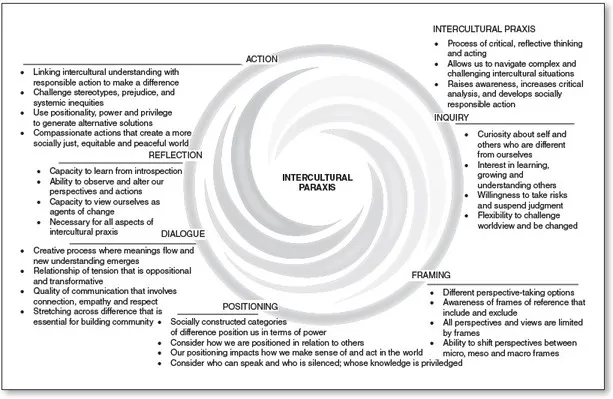

Consisting of six dimensions (inquiry, framing, positioning, dialogue, reflection, and action), intercultural praxis encourages us to approach intercultural communication not as an “object” of study but, rather, as a way of being, thinking, and acting (Sorrells, 2013; Sorrells & Nakagawa, 2008). Intercultural praxis entails (a) being willing to ask questions and suspend judgment (inquiry); (b) clarifying cultural frames of reference and shifting frames from micro to meso to macro levels (framing); (c) examining who/where you are in relation to others in terms of power relations (positioning); (d) engaging in open exchange of ideas (dialogue); (e) looking back and accessing your thoughts and action (reflection); and (f) taking informed and ethical actions toward a more just and equitable society. (See Figure 1.1.)

Engaging in intercultural praxis means we open ourselves to the possibility of becoming more conscious, aware, and socially responsible individuals. It also means we develop self-reflexivity and agency within unequal relations of power that shape intercultural interactions. It can be both exciting and frightening to think that every intercultural encounter is a moment of learning, growth, and transformation. As the world is becoming more complex and diverse, a predetermined set of skills or techniques does not guarantee effective and ethical communication. Using intercultural praxis cultivates our analytical and observational skills, develops ethical and affective orientations, and encourages responsible action as we relate with one another across cultural differences.

A central intention of the intercultural praxis model is to understand and address the intersection of cultural differences and hierarchies of power in intercultural interactions and scholarly pursuits. When people from diverse backgrounds come together, differences are there. Cultural, ethnic, and racial differences that manifest in language, dress, behaviors, attitudes, values, histories, and worldviews are real. Yet the challenge in intercultural communication is not only about differences; racial, ethnic, cultural, gender, and national differences are always and inevitably situated within relations of power. Our exploration of the confluence of cultural differences with power differences is facilitated by keeping the following questions in mind:

- Who/what is considered different and why?

- What/who is considered the norm?

- Who/what is diminished or dehumanized when dominant cultural perspectives and practices are normalized?

- What institutions, rhetoric, and discourses are used to normalize, justify, and perpetuate hierarchies of difference? Who benefits?

- How am I personally—and the cultural groups to which I belong—advantaged/disadvantaged by maintaining hierarchies of cultural difference (race, gender, etc.)?

- How can our individual and collective cultural resources be used to envision and enact alternative paradigms that elevate and uplift the human community?

Framing the Past

Figure 1.1 Intercultural Praxis Model

In intercultural praxis, framing is a process by which you zoom in and out through your analytical lens to evaluate a situation from micro, meso, and macro perspectives. In using intercultural praxis to review the history of the field, it is important to note that any act of remembering is always partial and incomplete (including this essay). Moreover, the frame of reference we use can radically change the nature of “history” that we accept as true. For example, if you were to write a book on your country’s history, what would you include? Would you write about the major wars and histories of conquest from the victor’s point of view? Would you focus on famous historical figures and powerful political leaders? Or would you focus on the lives of ordinary people who, collectively, shaped the history of your country? Shifting from a macrolevel to a microlevel framework, you see how different narratives and perspectives emerge. Thus, historicizing the field of intercultural communication requires being mindful of the frame of reference we use to define what constitutes the history of the field. Consider o...