![]()

Chapter 1

Are humans the pinnacle of evolution?

We like to think we’re at the top of the evolutionary tree – but are we? Is there even a tree to climb to the top of?

Ladder, chain or tree?

More than two thousand years ago, the Greek philosopher Aristotle wrote about the scala naturae, or ‘ladder of Nature.’ He ranked organisms (living things) in a hierarchical order, from the lowliest – simple plants – to the most advanced – human beings. This wasn’t based just on feeling superior to mushrooms or flatfish. He proposed that organisms have different types of souls according to their nature and needs. The soul, he claimed, gives the physical matter of the body its capabilities.

According to Aristotle, a plant has a soul capable only of growth and sustaining life, but an animal has a soul capable of growth, sustaining life, and moving around. A human is better still, as it can do all those and is also capable of reason. For the Ancient Greeks, the rational soul placed humans at the top of the ladder.

Aristotle distinguished within the broad categories of plant/animal/human, too. He considered trees to be superior to smaller plants, and blooded animals (such as wolves) to be superior to bloodless animals (such as spiders). The blooded/unblooded distinction coincides with the modern division of vertebrate/invertebrate (animals with or without a backbone).

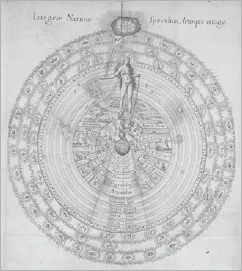

In the 3rd century AD, the Egyptian-Roman philosopher Plotinus added a new rung at the top of the ladder for the gods to stand on. With the coming of Christianity, Ancient Greek theories were assimilated into Christian thinking where possible. The ladder of nature became the ‘Great Chain of Being’. The pagan gods were replaced at the top by different classes of angel and archangel, with the Christian God at the very top. Just as Aristotle’s model had organisms on distinct rungs, ascending from lowest to highest, so the chain had discrete links. And although a chain could lie in a tangled heap on the floor, this one didn’t. It was extended vertically, with angels at the top and the lowest organisms – algae, perhaps – at the bottom.

Far more organisms were known in the Middle Ages than had been familiar to Aristotle, and more were constantly being discovered over the following centuries as European adventurers, explorers and conquerors travelled further afield. The Americas, Asia, the Pacific Islands and Australasia all yielded new beings that had to be fitted into the chain, and they were. The prevalent belief was that Creation was full – God had created a perfect world, with an organism to occupy every niche, leaving no gap unfilled, even if people had not yet found all the organisms.

In a chain, everything is linked. Instead of taking a step up from plants to animals, as on a ladder, the chain model proposed intermediate links. These could be represented by organisms that were thought to share aspects of both – so shellfish or sponges that don’t move are on the border between plants and animals. But some odd hybrids were also described, such as barnacle geese, which were thought to grow on trees.

No change

The models of a ladder and of a chain both describe a static order. The Abrahamic religions make the fixity of nature explicit. The account of Creation given in Genesis is of God creating the plants, then the animals and, finally, humans. The other organisms were created purely to serve humankind and so humankind is clearly their superior. Just as important as humans’ superiority is the idea that all organisms have existed from the start. Creation was both perfect and complete: the world did not change and had not changed. How could it, if God had created a perfect world?

BARNACLE GEESE – HATCHED FROM BARNACLES, GROWN ON TREES

How could a society with no notion of migratory birds account for the fact that they never saw barnacle goslings or saw the parents sitting on a nest? They concluded that the geese hatched from barnacles. Barnacles are often found on timber in the sea. Clearly the wood had fallen into the sea with the goose-pods growing. Perhaps they were produced from the sap in the wood. The barnacles hung down from timbers in their hundreds and – when no one was looking – grew to maturity and the geese flew away or dropped into the sea to swim off. Now we know that barnacle goslings hatch from eggs, like any other bird.

Oh, but look . . .

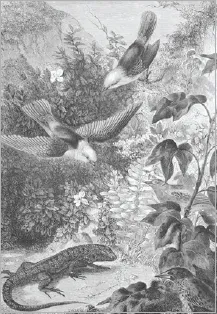

The discovery of fossils challenged that notion. The fossils of sea creatures were found far inland, even on hills and mountains. And then, starting in earnest at the beginning of the 19th century, people began to uncover fossils of animals very unlike those that were alive at the time. First the fossil remains of plesiosaurs and ichthyosaurs were discovered, then Iguanodon and Hadrosaurus followed. The conclusion that large, unfamiliar animals had once walked (and swum) the Earth became irresistible for many scientists, though others clung to the Creation narrative and tried to explain away the discoveries. In the second half of the 19th century and the first years of the 20th, the great dinosaurs were discovered – Apatosaurus, Tyrannosaurus, Stegosaurus, Triceratops – and the human view of the past changed forever.

Evolution evolving

The theory of evolution did not spring fully formed from nowhere (or from Darwin’s brain) in the mid-19th century. It had been a long time brewing.

Even before Aristotle, some of the Greeks had protoevolutionary ideas.

Anaximander (C.611–547BC) proposed that the first animals were formed from bubbling mud. They had lived in the water at first, but as the land and water separated over time, some of them adapted to living on land. He believed that even humans had developed from earlier, fish-like animals. After a promising start, though, western thought became bogged down in the no-change theory of Creation. Evolutionary ideas did not reemerge in the West for around 2,000 years.

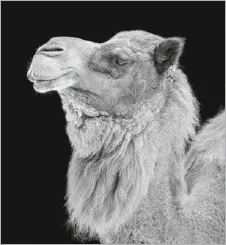

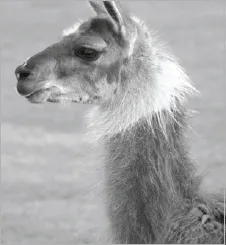

From the 18th century, evidence that organisms do change was piling up. Greater interest in taxonomy, especially after the work of the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707–78), showed there were clear similarities between some species widely separated by geography. Camels and llamas are similar, as are jaguars and leopards, yet there is an ocean between their territories. Scientists attempted to explain these puzzles first within the framework of traditional Christian thinking. Perhaps organisms had started off perfect but degenerated over time. Or, if they all started out in the far north and moved southwards, that would explain how animals in the New World and Old World could resemble one another – both the llama and the camel could have degenerated from some ur-camelid as they travelled through time and terrain. Genesis made allowance for degeneration, in a way, since the Fall of Man had sullied Creation. Humankind could still be the top of the heap of non-angelic beings, even if the lower rungs or links shifted a little.

Species similarities: camels are an Old World animal, living in North Africa, the Middle East and across Mongolia. Llamas are the related New World version, found in South America.

The French naturalist Jean-Baptiste Lamarck (1744–1829) suggested that rather than degenerating, organisms underwent improvement, or at least adaptation. Change came about, in his view, as animals strove to survive. So, for example, an animal such as a giraffe that was constantly reaching its head up to get at the juiciest leaves high up in a tree would stretch its neck in the process, making its neck slightly longer. The results of this stretching were passed on to the next generation, so over time the animal’s descendants would have a longer and longer neck. In this way, striving was piled upon inheritance in a continuous sequence.

Erasmus Darwin (1731–1802), a contemporary of Lamarck, shared this view. He put forward the idea that all life had evolved from a common ancestor over a very long period of time. The history of life could be seen as a ‘single filament’ joining past and present, He also suggested the notion of sexual selection. Many animals compete for mates and so: ‘The final course of this contest among males seems to be, that the strongest and most active animal should propagate the species which should thus be improved.’

Evolution to the fore

In 1831, Erasmus’s grandson, Charles Darwin (1809–82), was just 22 years old when he set off on a journey around the world on the surveying ship HMS Beagle. He held the position of official naturalist for the voyage, and over the next four years and nine months he would collect samples of plants, animals and fossils, make copious notes, observe animals and plants in their natural habitats, and wonder at both the diversity and the remarkable similarities he witnessed in the natural world. Whenever he arrived at port his latest discoveries would be boxed up and sent back to be studied and marvelled at by the scientific community back in England. By the time he returned, he had become a renowned scientist. But he did not turn with any great resolve to the question of how that diversity and alikeness had developed until 1838, and only began writing in earnest in 1842. It took him until 1859 to finish and publish what became a world-changing book, On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection.

Darwin not only set out to assert that species change over time but als...