![]()

1

CITIZENS UNITED

Corporate Money Talks

Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission1 is the Roberts Court’s most important First Amendment decision. It is also the most misunderstood (partly because the opinions in the case run to 176 pages, and few people have read them). It freed corporations to spend without limit to support or oppose candidates for political office.

The Citizens United decision is in many ways the best example of what the Roberts Court has been doing with the First Amendment:

•It was a 5–4 decision, with the justices divided along familiar conservative-liberal lines according to the party of the president who appointed them.

•The majority opinion was written by Justice Anthony Kennedy, the court’s most enthusiastic First Amendment supporter and the author of several of its most important free speech decisions.

•The result strongly advanced corporate and conservative political interests.

•Abandoning any commitment to judicial restraint, the court converted a narrow dispute into a major change in American law, overruled a long-standing precedent to arrive at the desired result, and delivered the broadest ruling imaginable.

•The court aggressively employed merciless, unforgiving scrutiny to the justifications offered by the government for restricting corporate spending.

•The decision had significant real-world consequences, greatly increasing the amount of money spent on political campaigns and creating new sources for campaign funding. Its reasoning led almost immediately to the creation of super PACs (political action committees). Although the court did not actually say, “money is speech,” it held that “independent expenditures”—spending on elections not coordinated with a candidate—are incapable of causing corruption, are treated as “speech,” and are therefore protected by the First Amendment. Today, more money goes into elections from independent expenditures than from contributions to candidates.

The decision was not a surprise.

The foundation for the decision was laid by the 1971 Powell memo; the result was engineered forty years later by the Roberts Court.

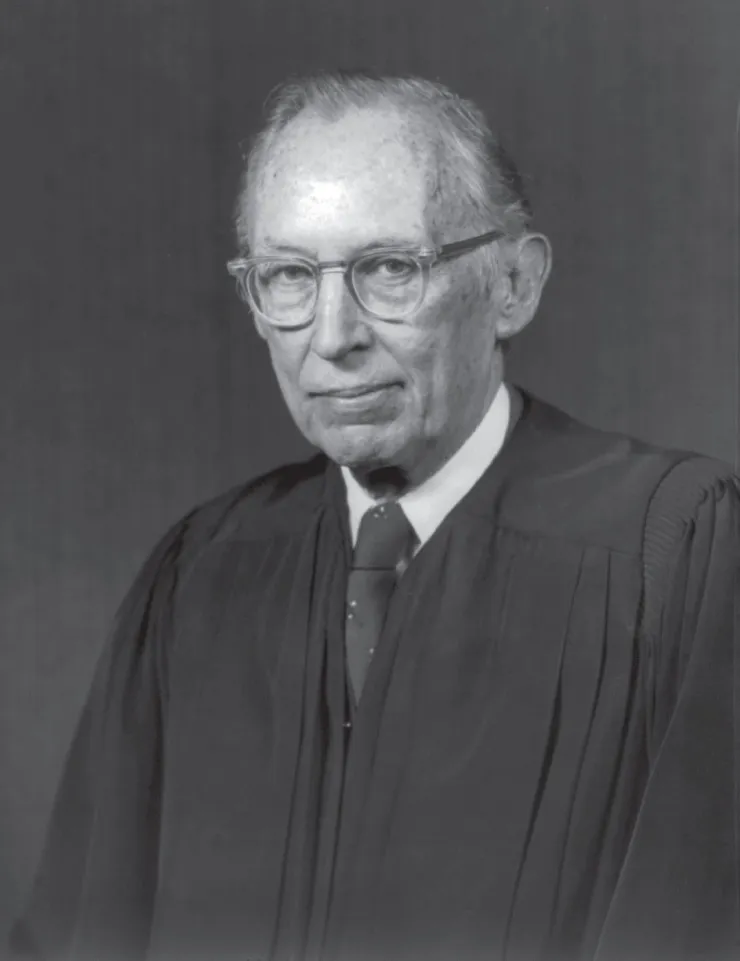

Beyond the memo’s call for conservative activism, Lewis Powell contributed more directly to the ultimate Citizens United ruling when he became a justice of the Supreme Court. He authored the majority opinion in a 1978 case called First National Bank of Boston v. Bellotti.2 A Massachusetts law prohibited corporations from spending to oppose a ballot proposition that would establish a state income tax. A group of corporations challenged the law as a violation of their First Amendment right of free speech. This presented a major undecided issue: Do corporations have First Amendment rights? Justice Powell artfully dodged it, saying the question was not whether corporations “have” First Amendment rights, but whether the law “abridges expression that the First Amendment was meant to protect.” The corporations proposed to engage in core political speech about an election, and this was speech “at the heart of the First Amendment protection.” The question, therefore, was “whether the corporate identity of the speaker deprives this proposed speech of what would otherwise be its clear entitlement to protection.” Powell’s answer was no. In other words, the First Amendment protects the speech regardless of the corporate identity of the speaker. This became one of the major themes of the Citizens United decision.

Justice Lewis Powell, 1976.

So, What Was the Citizens United Case About?

Back when bipartisan congressional action was possible, Republican John McCain and Democrat Russ Feingold collaborated on a bill called the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002. Known as the McCain-Feingold law, it contained a provision that prohibited both corporations and unions from using their funds on communications—mainly television advertising—that support or oppose a candidate for federal office. The law covered all corporations, small and large, nonprofit as well as for profit; it did exempt media corporations.

In 1990, in Austin v. Michigan Chamber of Commerce,3 the court had upheld a very similar provision against constitutional attack. Michigan law barred corporations from making independent expenditures supporting or opposing candidates for state office. The Michigan Chamber of Commerce, itself a nonprofit corporation, challenged the law as a violation of its First Amendment rights. Justice Thurgood Marshall wrote the opinion for the 6–3 majority, upholding the law as serving the state’s interest in preventing corruption or the appearance of corruption. Justices Antonin Scalia and Anthony Kennedy filed spirited dissents.

Austin was the law when McCain-Feingold passed and until the court handed down Citizens United.

Citizens United is a nonprofit corporation that engages in conservative advocacy. During the 2008 presidential primary campaign, it produced a ninety-minute documentary film called Hillary: The Movie. It was an attack on Hillary Clinton. As characterized by the court, the film was “a feature-length negative advertisement that urges viewers to vote against Senator Clinton for President.” (Citizens United’s president and producer of the film, David Bossie, later earned a position as Donald Trump’s deputy campaign manager.) Citizens United released the film in some theaters and on DVD but wanted to increase distribution by putting it on cable television using video on demand (VOD). Fearing that doing so might violate the McCain-Feingold law, Citizens United sued the Federal Election Commission (FEC), seeking a determination that showing its film was not illegal.

Citizens United argued that the McCain-Feingold provision on electioneering by corporations did not apply to its movie. The provision was targeted at television political ads, not feature length films or VOD. And Citizens United contended the law did not apply to it, a nonprofit whose donors were mostly individuals. In the trial court, Citizens United formally stipulated that it was challenging the law only as applied to it and its film; it was not challenging the constitutionality of the law “on its face”—that is, as it might restrict any corporation and any ad. The trial court ruled against Citizens United, finding that the law applied and did not violate the First Amendment. Citizens United appealed.

The Supreme Court heard arguments twice, first on March 24, 2009. The experienced practitioner representing Citizens United, Theodore Olson, tried to win by persuading the justices to decide the case narrowly. His position stuck to the modest contentions made by Citizens United in the trial court: the provision of the McCain-Feinberg law did not apply to a full-length feature or VOD, as opposed to television commercials, and it did not apply to a nonprofit advocacy group like Citizens United. He did not suggest overruling the Austin decision or any other precedent.

When the justices met to deliberate after the argument, they voted 5–4 in the corporation’s favor, and Chief Justice John Roberts assigned the writing of the majority opinion to himself. (The court’s practice is that, when the chief justice is in the majority, he designates who will write the majority opinion. This is a significant power of the chief justice, as he or she may be able to influence how the case will be decided, and what kind of precedent it will set, by choosing one or another justice as the author.)

Roberts circulated to the justices a draft that decided the case on narrow grounds. But Justice Kennedy, supported by the other conservatives, then circulated a concurring opinion that broadly condemned the law on its face (in all its possible applications), rejected any narrow approach to deciding the case, and called for overruling Austin and any other precedents in the way. Apparently persuaded, Roberts then agreed to sign on and make the Kennedy version the majority opinion. That caused Justice David Souter, in his last term on the court before his retirement, to draft an uncharacteristically scathing dissent claiming the court was violating its own rules by deciding the case on grounds not raised by any party. In response, the majority justices decided to withhold any decision and set the case for reargument at a special session on September 9, 2009, after Souter’s departure. The court ordered the parties to submit briefs on whether the court should overrule the 1990 Austin case. The writing was on the wall.4

As President Obama's solicitor general, Elena Kagan presented the second argument for the government. It was her first appellate argument in any court. She performed valiantly, in damage-control mode, but how the justices would rule was a foregone conclusion. On January 21, 2010, the court handed down its decision, holding that the McCain-Feingold law violated the First Amendment.

The Majority Decision

In order to find the McCain-Feingold law unconstitutional, Justice Kennedy’s majority opinion had to jump over several analytical hurdles. Here are the steps in the court’s logic.

The Case Should Not Be Decided Narrowly

First, the Kennedy opinion disposed of the contentions that would have allowed the court to decide the case narrowly and without invalidating the law on its face. The majority refused to read the law as not applying to the Hillary film, or to VOD, or to a nonprofit’s political speech funded mostly by individuals. Any of these contentions would have allowed Citizens United to win without having the law held unconstitutional across the board. Justice Kennedy also brushed off the fact that Citizens United had stipulated in the trial court to forego its challenge to the law on its face and rely only on its arguments about how the law applied to it. Kennedy asserted, without acknowledging the irony, that the court must, “in an exercise of its judicial responsibility,” determine whether the law was unconstitutional on its face. Otherwise, Kennedy said, “the substantial, nationwide chilling effect” of the prohibition would be prolonged.5

The court has often struck down laws that it says create a “chilling effect” on speech, causing people to self-censor and refrain from saying what they want to say. The laws are usually broad and uncertain and often treat the forbidden speech as a criminal offense, deterring would-be speakers from taking the risk of saying what they want to say. The majority in Citizens United found a chilling effect in the uncertainty about exactly what communications the government would say were prohibited. The campaign finance regulations were exceedingly complex, and the FEC had adopted 568 pages of regulations, 1,278 pages of explanations and 1,771 advisory opinions. Kennedy said, “If parties want to avoid litigation and the possibility of civil and criminal penalties, they must either refrain from speaking or ask the FEC to issue an advisory opinion approving of the speech in question. . . . This is an unprecedented governmental intervention into the realm of speech.”

The Law’s Criminal Penalties Are Serious

The law covered all the millions of American corporations, including mom-and-pop operations, small single-shareholder companies, and nonprofits. Spending to support or oppose a candidate would subject all these kinds of corporations to criminal liability, accentuating the law’s chilling effect. Kennedy observed that the law “makes it a felony for all corporations—including nonprofit advocacy corporations—either to expressly advocate the election or defeat of candidates or to broadcast electioneering communications within 30 days of a primary election and 60 days of a general election.” Thus, organizations like the Sierra Club, the National Rifle Association, and the American Civil Liberties Union—all corporations—would commit felonies if they supported or opposed candidates whose positions they favored or abhorred.

(Raising troubling but hypothetical applications is apt...