![]()

1

Applying psychology

In this chapter you will learn:

- the difference between applied and academic psychology

- about the historical beginnings of applied psychology

- to identify different areas and approaches of applied psychology.

Psychology is the study of people – how they think, what they experience, why they act as they do and what motivates them. It’s a fascinating subject, and a massive one.

We spend most of our conscious lives making sense of people, in one way or another. In fact, we begin from the moment we are tiny babies. Even the smallest infants arrive ‘pre-tuned’ to other people – ready to respond to human voices, faces and touch. A lot of our infancy and childhood is spent learning how to deal with social life, beginning with how to communicate effectively, and moving on to dealing with other family members, friends, school or work colleagues and eventually lovers and partners.

So we are all ‘natural’ psychologists in some ways, and lots of the time we are very good at it. But not always. People are enormously complicated, and even when we think we know someone really well they can still surprise us. We all have a lot of potential which doesn’t show on the surface. So don’t be fooled by anyone who tells you that people are easy to understand – they are not. There’s much more to everyone than meets the eye.

And that’s where psychology comes in. Psychologists look below the surface, to understand the underlying processes and mechanisms which produce human behaviour. They study how people interact, both in groups and in pairs, and what sorts of communication are likely to become effective. And they look at the different areas and functions of the human mind.

We looked at the main areas of psychology in the companion volume to this book: Understand Psychology. If you’ve read that, you’ll have a pretty fair idea of what those are, and some of the kinds of knowledge which psychologists have developed. Or you might have read some other psychology books, which have also given you some knowledge of the discipline. There’s quite a lot around. But you don’t need to have read Understand Psychology to understand this book. They go together and complement one another, but they don’t depend on each other.

Applying psychology

In this book, we are going to look at psychology from a slightly different angle – from the point of view of how psychology has been applied to some human questions and issues. Psychology has been used in many areas of life, ranging from how we bring up our children to how astronauts deal with weightlessness. Obviously, we won’t be able to look at all of them. But we can take a look at some of the main areas of applied psychology, and that should give us a better understanding of some of the ways that psychology can contribute to our everyday lives.

Insight

Trying to define where psychology has been applied is a bit like catching water in a net. People are always finding new ways to apply psychology, because who we are and how we think affects just about everything we do.

Different sections of this book will be dealing with different aspects of applied psychology. We’ll begin by looking at how knowledge obtained from traditional ‘pure’ psychological research has been applied. There have been quite a few spin-offs from academic research areas, so in the next four chapters we’ll look at some of the applications of knowledge from social psychology, cognitive psychology, bio-psychology and developmental psychology.

Then we’ll look at some of the areas which relate particularly to how psychologists work in the community as a whole. We’ll begin with clinical psychology, since that is one of the oldest and most well-established areas of applied psychology. Then we’ll go on to look at several other areas: health psychology, forensic psychology, educational psychology, and the applied psychology of teaching and learning.

The next group of chapters is concerned with how psychology has been applied to working life, or to particular vocations. They deal with occupational psychology, which has to do with working out the right types of work for different people; with organizational psychology, which is concerned with the human aspects of management; with engineering and design psychology, which is concerned with how people interact with objects and machines; and with space psychology, which as its name suggests is concerned with the psychological dimensions of space exploration.

This final group of chapters deals with some of the broader aspects of social living. We begin with sport psychology, an area of applied psychology which has existed for a long time and is becoming more and more important as our knowledge grows. The increasing professionalization of sport means that we could, of course, make a case for putting it with the previous set of chapters, but it can equally well link with the rest of the chapters in this set. We go on to look at consumer psychology, which includes the psychology of advertising and consumer behaviour – something that affects all of our lives. Then we look at environmental psychology, and how the environment we live in influences our experience, and then finally we will look at the increasingly important area of political psychology.

Naturally, that doesn’t cover all of the areas of applied psychology. Psychology has relevance anywhere human beings are active and that, almost by definition, covers just about all aspects of social life. But this book ought to give you an idea of the range and scope of applied psychology – and perhaps some ideas for other areas where psychology could usefully contribute to our everyday lives.

Applied psychology – some history

Applied psychology is much older than a lot of people think. In fact, psychology has been applied from the moment that psychology became developed enough to make predictions. Those theories were brought into action to address small everyday problems, in much the same way that modern psychologists are often called on to help in the solving of small everyday issues. But that type of applied psychology is very informal, and doesn’t tend to stay in the records.

Insight

Some (applied) psychologists have argued that actually, applied psychology came first and ‘pure’ psychology came later. Although academic psychology traces its academic roots in experimental philosophy, it has equally strong roots in clinical medicine and in the explanations of crowd psychology which were developed in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries to explain social riots.

The applied psychology which has gone down in the history of the discipline began at the beginning of the last century, some say with the work of the French psychologist Alfred Binet. Binet had been observing children, and had particularly been looking at how they become able to tackle different problems at different ages. He was also mulling over a particular educational challenge. The French government was setting up special schooling to help those children who were what we would now call educationally challenged. These special schools were very advanced, and also provided full boarding for their children, so they were quite attractive to many poor families.

Binet needed to sort out a way of distinguishing between children who were genuinely ‘slow’, and children who were just pretending to be slow in order to get into the new schools. With a problem like this, you can’t just judge it on how those children speak or what they look like (despite what some people think) because some very bright children speak quite slowly, and some children who find it hard to grasp new ideas seem perfectly ordinary on the surface.

Binet had observed that it wasn’t a matter of such children being unable to learn. Instead, they just learned a bit more slowly than others. For example: a seven-year-old who fell into this category might be learning the kinds of things that an ordinary five-year-old would normally be tackling. So what Binet did was to use his research on children’s problem-solving to put together the very first intelligence test. He assembled a series of puzzles of different kinds – some practical, some paper-and-pencil, and tried them out on a lot of children. The results let him see what ordinary children might be expected to do at different ages. That meant that he could use the test to form an idea of a child’s mental age.

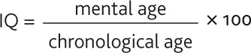

The idea of ‘mental age’ led on to a concept which has become everyday knowledge in our society – IQ, or the intelligence quotient. It’s been through a lot of adjusting, but it originally came from Binet’s formula:

The way the formula works out is that someone whose mental age is lower than their chronological age – their actual age in years – will have an IQ below 100. The lower it is, the further behind they will be. Someone whose mental age is exactly the same as their chronological age – in other words, someone who is completely ‘normal’ in that respect – will end up with an IQ of 100. Someone whose mental age is higher than their chronological age – a precocious or advanced child – will end up with an IQ above 100. The higher it is, the further ahead of other children of their age they will be.

This gave the French government a system for selecting children for special schooling – something which was very advanced social policy for its time. It meant that these children, rather than being rejected by society as a whole, could get the education they needed. It also meant that they could learn to become independent, participating members of society, because their education was paced at a speed that they could cope with. That was one of the very first systematic uses of applied psychology.

Like any other science, though, psychology can be abused, or used for negative purposes. Binet’s work on intelligence testing was seized on and transformed by other psychologists (and by politicians in other societies), until it became completely different from the system which Binet had developed. In fact, it ended up being used in ways which were completely opposite to the ones which he had recommended. Eventually, those ideas were used (on the basis of some very dodgy science) to rationalize racist immigration policies and compulsory sterilization of imbeciles in the USA. Those policies in their turn were much admired by the German Nazis, and used as the basis for their social segregation of Jews, and ultimately as part of their rationalization of the Holocaust. (If you’re interested, you can find out more about this in Steven Jay Gould’s excellent book The Mismeasure of Man.)

Insight

The misuse of intelligence test results for ideological aims continued right through the twentieth century, and is sometimes used as the basis for racist propaganda even today. But it has no foundation in real science.

Any knowledge which works can be used for good or for evil. That’s the nature of effective knowledge. Applied psychology isn’t often abused so dramatically today, but any knowledge which has the potential to enrich people’s lives also has the potential for abuse. A good understanding of non-verbal communication, for example, can be applied to help people to communicate with one another more effectively and to break down social prejudices. But it can also be applied to manipulate others so that they are more likely to act in ways that the manipulator wants them to act. Understanding how psychology can be, and has been, applied helps us to distinguish between manipulative and positive uses of that knowledge more effectively.

Academic and applied psychology

Academic psychology is largely concerned with developing psychological knowledge – exploring our understanding of human beings, mental processes, developing better ways of looking at human experience, and observing how physiological and developmental factors influence people. That knowledge, for the most part, is gathered for its own sake – it all helps us to understand more about people and what makes them ‘tick’.

That knowledge often has implications for our everyday lives. Psychologists studying memory, for example, did so because it was an intrinsically interesting area of study. But the knowledge that they gathered can tell us a great deal about how we can improve our memories, or how we should go about preparing for exams if we want to remember the material effectively. It wasn’t collected for applied reasons, but once it is there, it can be used.

A great deal of applied psychology is like that. Psychologists have brought together knowledge and insights that have been gleaned from academic psychology, and applied them to everyday life. For the most part, that works very well. But there are still some tensions between the two.

PROBABILITY AND CERTAINTY

One of the most important tensions relates to the question of certainty. If you look carefully at psychological reports – or indeed, at the research reports of any scientist – you will discover that their findings are always expressed tentatively, leaving room for alternative possibilities. Research scientists know that nothing can ever be definitively proven – there is always room for error or uncertainty even in the most promising of research findings.

An applied psychologist is interested in using knowledge in practice, though. So in applied psychology, a finding which implies a relationship between a cause and an effect is taken and used as if that relationship were fairly well established. It’s a reasonable thing to do, partly because the ways that professional psychologists use knowledge always allows for alternative possibilities, and partly because academic knowledge is always expressed like that anyway. A scientist may express uncertainty about a finding even when they are 99 per cent, or 95 per cent confident of their results. In everyday living, we treat that as strong enough to act on, even though it isn’t absolutely definite.

Applied psychologists have all been ...