eBook - ePub

Cultures and Traditions of Wordplay and Wordplay Research

Esme Winter-Froemel, Verena Thaler, Esme Winter-Froemel, Verena Thaler

This is a test

Share book

- 299 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Cultures and Traditions of Wordplay and Wordplay Research

Esme Winter-Froemel, Verena Thaler, Esme Winter-Froemel, Verena Thaler

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Cultures and Traditions of Wordplay and Wordplay Research an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Cultures and Traditions of Wordplay and Wordplay Research by Esme Winter-Froemel, Verena Thaler, Esme Winter-Froemel, Verena Thaler in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Langues et linguistique & Linguistique. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

IIITraditions of wordplay in different social and cultural settings

Eline Zenner and Dirk Geeraerts

One does not simply process memes: Image macros as multimodal constructions

Abstract: This paper presents a Cognitive Linguistic analysis of image macros, a subgenre of Internet memes. Internet memes encompass all kinds of online objects that are copied and imitated, altered and modified, propagated and diffused by participants on the web. Image macros are a specific example of such online content, consisting of text superimposed on an image. Whereas the image and discursive theme of image macros are typically fairly consistent in the replication process, the text is particularly open to the online “remix culture” that characterizes Internet memes. Given this pivotal role of variation and modification, it is not straightforward to define the ultimate set of characteristic features of an image macro. The first goal of this paper is to define image macros in a way that captures precisely this interplay between conventionality and creativity. To this end, we will combine insights from Construction Grammar and prototype theory, presenting image macros as multimodal constructions that share characteristics with jokes and traditional wordplay. Moreover, the verbal elements in the memes often also include such instances of traditional wordplay. A second goal of our paper is to explore the processing difficulties involved in these occurrences of traditional wordplay in image macros. Specifically, we present four dimensions that together indicate how the image macros vary along a typicality cline with regard to the degree of multimodality, multilingualism, intra-genre intertextuality and external referencing included in the construction. As such, we open up promising research avenues for the study of this often banalized, but highly popular subgenre of Internet memes.

Keywords: Construction Grammar, constructions, image macros, Internet memes, intertextuality, monolingualism, multilingualism, multimodality, processing wordplay, prototypes

1Introduction: Genes, memes and the worldwide web

In 1976 Richard Dawkins coined the term meme (a portmanteau of mimesis and gene), by analogy with the biological notion of a gene, to refer to any unit of cultural transmission (Dawkins 1976; and see Blackmore 1999 as important but disputed landmark). Although the memetic approach is often (justly) criticized for taking the biological analogy too far and for underestimating the role of the human being as agent in memetic evolution, several parallels between biological and cultural transmission are at the very least noteworthy: both genes and memes are characterized by (i) gradual propagation from individual to society; (ii) reproduction via copying and imitation; and (iii) diffusion through competition and selection. Leaving the debate on the precise nature of the link between genetics and memetics to one side, it is not very difficult to identify a wide variety of examples of cultural transmission that follow these three parameters, such as the spread of specific architectural styles (e.g. art deco, postmodern architecture), types of clothing (e.g. the advent of “hipsters”) and ways of teaching (e.g. naturalistic versus constructivist teaching). A less functional but famous example is “Kilroy was here”. This multimodal meme, consisting of a cartoon-like face peeping over a straight line representing a wall accompanied by the phrase “Kilroy was here”, finds its origin in World War II, and popped up in all sorts of places during and after the war. Bjarneskans, Gronnevik, and Sandberg (1999) describe several factors that have contributed to the success of “Kilroy was here”: the artefact is easy to reproduce, but it is at the same time sensitive to mutation and creative input; it lacks univocal meaning; it does not require direct host-to-host contact for reproduction, though users still experience a sense of “belonging to” when sharing the meme. Shifman (2014) considers precisely these characteristics as the pivotal elements in the rapid emergence of a new and highly popular subbranch of memes, namely Internet memes.

Indeed, the advent of the Internet, and of Web 2.0 and its social networks in particular, gave rise to a large number of artefacts that we can easily classify as memes in the Dawkins sense of the word (Milner 2013, 2016; Nooney and Port-wood-Stacer 2014). These so-called Internet memes encompass all kinds of online objects that are mixed and remixed, copied and imitated, propagated and diffused by participants on the web. The principle of imitation and selection is clearly visible in the online evaluation systems for these types of Internet content, such as the “like”-thumb on Facebook or the up- and downvoting system on Reddit. Additionally, Shifman (2014: 41) identifies three core elements that define Internet memes: they should be conceived of as

(a) a group of digital items sharing common characteristics of form, and / or stance, which

(b) where created with awareness of each other, and (c) were circulated, imitated, and / or transformed via the Internet by many users.

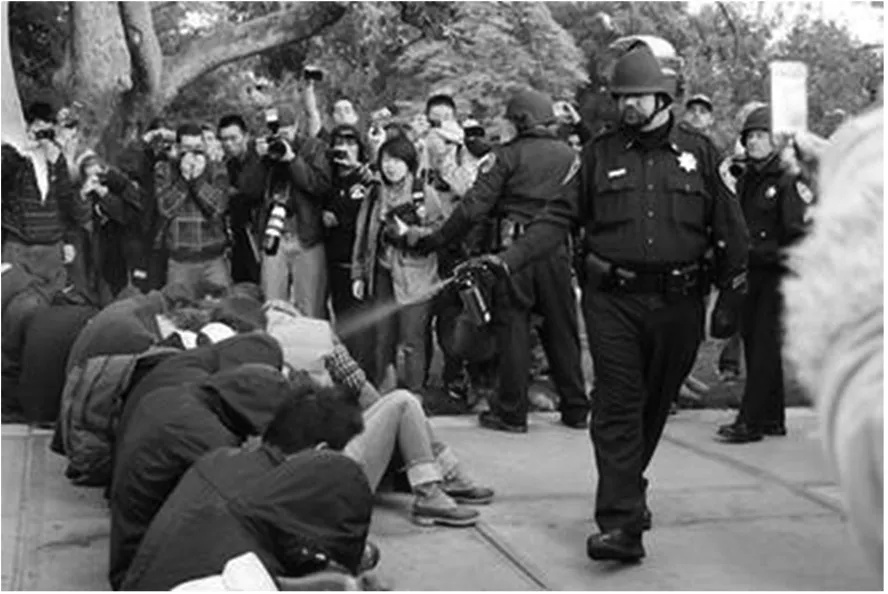

In practice, Internet memes can take the form of purely visual, purely verbal or explicitly multimodal items (Dagsson Moskopp and Heller 2013: 73–186). The Pepperspray Cop (Milner 2013; Huntington 2016) is a prime example of a purely visual meme. It concerns the spread of a central image from the Occupy Wall-street movement115, in which we see a campus police officer use pepper spray on protestors who were (at least in the image) peacefully sitting on the ground (Figure 1). The spraying action hence seemed uncalled for. The image itself went viral, but the truly memetic content only emerged as Internet users started remixing the original image with all sorts of other (both trivial and iconic) images: the Pepper Spray Cop was for instance photoshopped onto the original Beatles album cover, on Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel (Figure 2), on scenes from Star Wars and likewise on images of bathrooms and restaurants. Although we will not elaborate on ways to differentiate between virals and memes (see Shifman 2014), it is crucial to appreciate that whereas the former are characterized only by imitation, the latter always also include a component of alteration and modification. The video “Gangnam Style”, an example of a multimodal Internet meme, can help further illustrate this point. The original video of the Korean singer PSY reached a record number of views on Youtube within days and was shared all over the world. For a long time, it was the most viewed video on YouTube. As the video grew more popular, people started making their own versions of the song, altering the lyrics, the visuals or both: YouTube now also contains videos such as Kim Jong Style or videos with English translations of the original Korean text. A meme was born.

Often intertextuality plays a pivotal role in the modifications made to original posts. Not surprisingly then, this is one of the key topics studied so far in research on Internet memes (Huntington 2016). Other topics include the verbal and visual rhetorical techniques used in creating a meme (e.g. synecdoche, metaphor, pastiche, and so-called “irritating” juxtapositions; Stroupe 2004; Jenkins 2014; Lou 2017), (critical) discourse analysis of the socio-political messages they communicate (Milner 2013; Nakamura 2014; Vickery 2014), marketing opportunities presented in memes and virals (Woerndl 2008) and methodological explorations of algorithms that can trace the propagation, longevity and peak circulation of memes (Bauckhage 2011; Leskovec, Backstrom, and Kleinberg 2009; Paradowski and Jonak 2012).

In this paper, we want to complement these perspectives with a Cognitive Linguistic analysis of wordplay in image macros, a specific form of Internet memes. Below, we firstly lay the necessary groundwork: Section 2 provides a working definition of image macros and discusses the reasons why these image macros form a prime locus for (multimodal) wordplay and punning. Additionally, we present the main objectives of this paper, viz. to define image macros in a way that adequately captures their potential for creative modulation, and to analyze the specific role of wordplay in image macros. We then round off the section with a brief presentation of the data collected for this study. Section 3 turns to an introduction of the Cognitive Linguistic framework as a suitable tool for defining image macros (see also Brône, Feyaerts, and Veale 2006 on the general applicability of the Cognitive Linguistic framework for humor research): similar to but expanding on Dancygier and Vandelanotte (2017), we show how we can conceive of these digital items as multimodal constructions. Section 4 then focuses on instances of wordplay in these image macros, presenting four dimensions along which to place them in terms of processing and complexity. The final section distils the most pertinent – if preliminary – insights that can be derived from the proof of concept presented in this paper.

2Image macros and wordplay: A match made in heaven

This paper focuses on one notable subcategory of Internet memes, so-called image macros. An image macro consists of text superimposed on an image. Whereas the image and discursive theme are typically fairly consistent in the replication process, the text of image macros is particularly open to the online “remix culture” that characterizes Internet memes (see Vickery 2014: 312). Figure 3 provides a good illustration of this working definition of image macros116, presenting an instance of the meme known as Advice Dog. This meme, which shows an image of a dog against a rainbow-like background, rests on irony, presenting something that is quite obviously poor advice as good advice. After the first Advice Dog meme appeared online many more instances were shared on the Internet (see Davison 2012 and Vickery 2014 for the history of the meme), sometimes with a different dog (or occasionally even a different animal), but always with modifications of the text: Internet users shared their own bits of “good” advice through Advice Dog. The surge of online platforms that allow users to easily and quickly generate their own versions of popular image macros such as Advice Dog has rapidly increased the popularity of image macros, leaving us with a massive inventory of image macros to analyze (see below).

As the example illustrates, it is not straightforward to isolate the ultimate set of characteristic features of an image macro: each individual element of the meme is open to modification, with some elements being more stable than others. The first goal of this paper is to define image macros in a way that cap...