![]()

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

This new edition of the Searching Skills Toolkit contains updated instructions and examples for searching a range of healthcare databases, highlighting new features which have evolved as a consequence of technological advances. The sections within some chapters have been reorganised in order to emphasise the steps of the search process and the hierarchy of evidence. There were many web sources included in the first edition, and these have been updated and added to. The chapter on reference management software now includes open source software, such as Mendeley and Zotero, and Appendix 2 on teaching resources contains a new training exercise, for trainers to use in their search skills sessions.

The details in this toolkit are correct at the time of going to press, but please be aware that the Internet is constantly evolving, and the features and appearance of some resources may change slightly as technology progresses. However, the principles and resources underpinning this toolkit are transferable and adaptable to any changes that might arise.

Additionally, this edition contains two new chapters. The first – Chapter 12: Quality improvement and value: sources – focuses on sources of information for health management, quality improvement and cost-effectiveness, to support evidence-based (EB) management decision-making. This chapter is particularly aimed at commissioners, policymakers and health managers. The second new chapter – Chapter 13: Patient information: sources – has been written to help health professionals find good quality health information for patients and their carers. Involvement in the treatment decision-making process is beneficial to the patient and the health service, and is high on government agendas, so it is important that patients have the right information to help them make informed choices that suit them.

Evidence-based medicine

The concept ‘evidence-based medicine’ was first used by David Sackett and colleagues at McMaster in Ontario, Canada in the early 1990s. It means

“… the integration of best research evidence with clinical expertise and patient values.”1

Thus the aim of evidence-based practice (EBP) is to improve the quality of information on which decisions are made.

EBP provides resources to help health professionals find the best quality information to answer their clinical questions. Without these resources, health professionals become overloaded with information, and don't have the time to appraise all the current material published.

In 1972, Archie Cochrane, a British epidemiologist, became concerned that most decisions about interventions were based on an unstructured selection of information, of varying quality.

When making choices at home, such as what car to buy, we usually do some background research, for example, ask friends, look at car magazines, television programmes about cars, etc. We don't have all the answers, not as professionals and not as human beings. We may have gut instincts to guide us, and these can be useful. But you cannot base your choice on gut instinct. Intuition based on professional expertise is part of the evidence-based practice concept, and can be applied to patient care, as long as it is supported by the best available research evidence.

Why search?

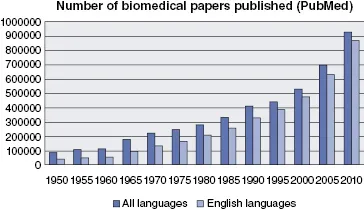

Searching skills are a necessity for all health professionals who want to stay up to date with best practice, particularly with the vast increase in research publication and the improved access to research via open access journals. Health professionals need to know how to find and appraise all this research. In 1865, the US National Library of Medicine began indexing medical literature, starting with 1600 references, and reaching 10 million by 2006.2 In 1999 there was an estimated 32 000 medical journals around the world;3 the medical literature expands at a rate of 7% per year, doubling approximately every 10–15 years.4 Currently 400 000 articles are added to the biomedical literature each year.5

Open access resources, such as Biomed Central (www.biomedcentral.com), provide access to 256 peer-reviewed journals covering a range of health-related specialities.

Reading and reviewing all the literature is not feasible for anyone, let alone busy health professionals. There are a range of resources available to help health professionals find the relevant information they require, but some sources contain better quality information and should be targeted first.

Evidence-based practice requires time and a resource investment, as there is so much research to read to inform practice. The aim of this Searching Skills Toolkit is to provide you with tools to find the best available evidence faster and more efficiently.

The toolkit has been divided up into chapters covering the basic skills and information you need to know to be an effective searcher. You may wish to work through the chapters in order, but for a quick overview we recommend starting with Chapter 2. This chapter outlines where to go to conduct a health information search depending on how much time you have, what type of publication you require or the specific topic area. A flow chart is included that directs you to search the higher quality evidence first. Where appropriate, references are given pointing you to the essential chapters you need to read, when you see this symbol:

How do you keep up to date

You can meet your current information needs by a variety of strategies:

- Toss a coin! – May be useful if there are only two options and you already know both.

- Guess – fine if you have the confidence, but what if you're asked to justify your decision?

- ‘Do no harm’ – don't try anything dangerously innovative!

- Training – remember what you learned during your professional training, which was considered optimum treatment 10 years ago.

- Ask colleagues – but if you ask three people, you may well get three opinions, so who is correct?

- Textbooks – how old are your textbooks and how decayed was the material in them when you bought them?

- Browse journals … getting better, but which ones do you choose?

- Literature searching – do you have access to, and the skills to search, bibliographic databases?

Apparently doctors use some 2 million pieces of information to manage patients6. Textbooks, journals and other existing information tools are not adequate for answering the questions that arise: textbooks are out of date, and ‘the signal-to-noise’ ratio of journals is too low for them to be useful in daily practice. When you see a patient, you usually generate at least one question; more questions arise than a doctor seems to recognise. Most questions concern treatment, some are highly complex. Many questions go unanswered, the main reason being lack of time. Some doctors rarely consider the merits of doing a formal electronic search (or of asking a librarian to do a search for them!).

- Write down one healthcare-related problem you recently encountered.

- What was the critical question?

- Did you answer it? If so, how?

Reflect on how you learn and keep up to date. How much time do you spend on each process? Activities usually identified include: attending lectures, conferences or tutorials, reading journals, textbooks or guidelines, clinical practice, small group learning, study groups, searching electronic resources, and speaking to colleagues and specialists. There is no right or wrong way to learn, but it is impossible to keep up to date with all the latest advances. One way to overcome the information overload is to use a push and pull strategy.

The ‘push’ method is the information we gather from the variety of sources that we receive across a wide spectrum of topics. This could be lectures, seminars, reading journals or magazines. To improve on this technique you should consider reading some pre-appraised source material. An example is the

EBM journal or

Clinical Evidence; this will cut down the time you spend reading.

The second method is the ‘pull’ technique, whereby you keep a record of the questions you formulate using the PIC...