![]()

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION: ENGINEERING AND THE ENGINEER

We recognize that we cannot survive on

meditation, poems, and sunsets.

We are restless.

We have an irresistible urge to dip our hands

into the stuff of the earth and do

something with it.

(Samuel C. Florman, engineer and author)

What do engineers and, by extension, many other technical professionals do? What roles and functions do they fulfill? This chapter uses several means to offer answers to those and similar questions and thus lay the foundation for the book’s treatment of the professional or non-technical aspects of engineering. First, the roles of engineers are presented in the context of their frequent, dynamic interaction with clients, owners, customers, and constructors-manufacturers and other implementers. Then the chapter presents several definitions of engineering as another means of suggesting what engineers do within the framework of various constraints. These definitions also introduce the engineer’s creative role. A discussion of leading, managing, and producing invites engineers to engage in all three roles early, beginning as college students. Included is a description of the seven qualities of effective leaders. Building, in the broadest sense, is discussed noting that this activity in its various forms is widely practiced across engineering. The wisdom of developing productive habits concludes the chapter.

THE PLAYING FIELD

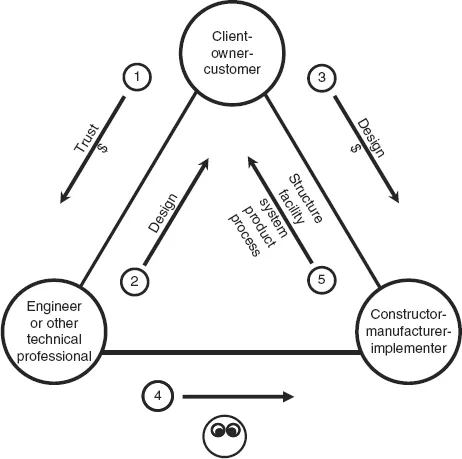

Engineers and other technical professionals interact dynamically among themselves and with clients, owners, customers, constructors, manufacturers, and other implementers. The interaction process, as illustrated in Figure 1.1, typically begins with a client, owner, or customer retaining a professional (e.g., engineer or architect) to conduct a study, perform preliminary designs, prepare a complete design, and deliver a contract package consisting of plans and specifications or other formal design. The client-owner-customer could be a private or public sector entity, such as a business or a municipality.

The client, owner, or customer then selects a constructor, manufacturer, or other implementer to produce the structure, facility, system, product, or process. The client, owner, or customer sometimes retains the professional to monitor the construction-manufacturing-implementation process so the final structure, facility, system, product, or process conforms to the original plans and specifications.

Design followed by manufacturing or construction can occur within a single organization. For a self-contained manufacturing organization, the bottom two vertices of the triangle shown in Figure 1.1 collapse into one point. Similarly the bottom two vertices become one in a design-build organization, that is, a single firm that both designs and builds structures, facilities, or systems.

Figure 1.1 is most likely to apply to engineers and other technical professionals who, at any time in their careers, might be at any one of the three vertices of the triangle. This book frequently refers to the triangular model and its variations. In one sense, managing and leading are the processes by which the various entities shown in Figure 1.1 interact with each other in the worlds of engineering and business.

DEFINITIONS OF ENGINEERING

Besides using the interactions shown in Figure 1.1 to show the role of engineers, we can also take a more fundamental approach to understanding “what engineers do,” that is, examine some time-tested definitions of engineering. Aeronautical engineer Theodore von Karman said “Scientists explore what is, engineers create what never has been” (ECPD 1974). This succinct statement suggests how science and engineering differ; that is, creativity is essential in the latter.

ABET, Inc. (ABET 2002) offers this definition of engineering which focuses on a mathematics and science base, judgment, economic considerations, and the goal of benefiting society: “Engineering is the profession in which a knowledge of the mathematical and natural sciences gained by study, experience, and practice is applied with judgment to develop ways to utilize, economically, the materials and forces of nature for the benefit of mankind.”

The creative and humanist dimensions of engineering were captured by Herbert Hoover, the 31st U.S. President, who had a long and distinguished engineering career. Stressing the thrill of creating and the satisfaction of enhancing the quality of life, he said (Fredrich 1989): “It is a great profession. There is the fascination of watching a figment of the imagination emerge, through the aid of science, to a plan on paper. Then it brings jobs and homes to men. Then it elevates the standards of living and adds to the comforts of life. That is the engineer’s high privilege.”

Finally, Professor Hardy Cross (1952), using direct, plain words, clearly captured the central, people-serving goal of engineering when he wrote: “It is not very important whether engineering is called a craft, a profession, or an art; under any name this study of man’s needs and of God’s gifts that they may be brought together is broad enough for a lifetime.”

Based in part on the preceding definitions, the following six essential features of engineering appear:

- Science-based

- Systematic—However, except for trivial problems, judgment and other qualitative considerations always enter in

- Creative and innovative

- Goal-oriented—Satisfy the requirements and get the job done on time and within budget

- Dynamic—Technology, laws, public values, clients, owners, customers, stakeholders, and the physical environment continuously change

- People-oriented—Both in doing and in results in that engineering is essential to the survival of human communities and to the quality of life

LEADING, MANAGING, AND PRODUCING: DECIDING, DIRECTING, AND DOING

Leading, Managing, and Producing Defined

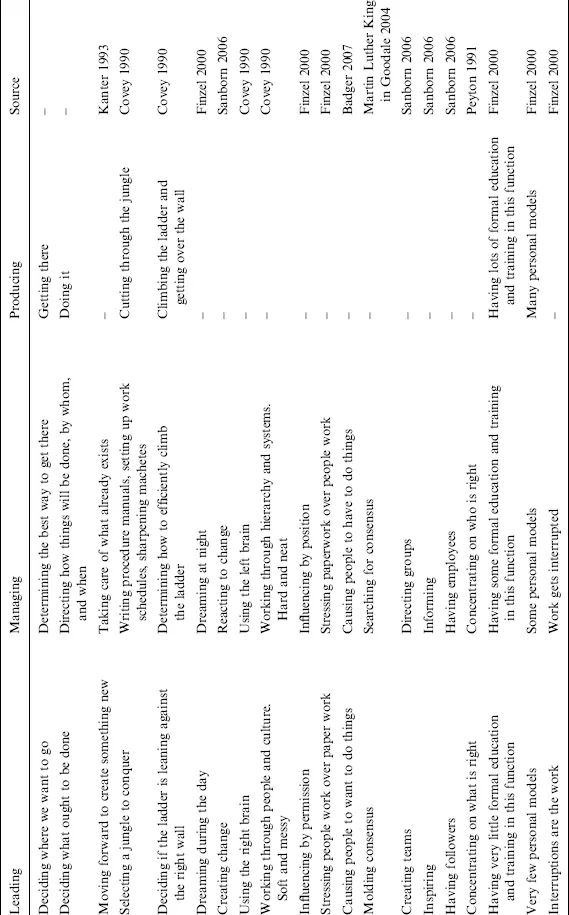

Another way of understanding what engineers and other technical personnel do, or could do, is examine their leading, managing, and producing roles. One paradigm for an organization, such as an engineering consulting firm, a manufacturing business, a government agency, an academic department, or a volunteer organization is that wholeness, vitality, and resiliency require attention to three different, but inextricably-related functions: leading, managing, and producing. The meaning of each of these terms is illustrated by the comparisons presented in Table 1.1. In a simplified sense, the leading, managing, and producing functions can also be represented by three Ds: deciding, directing, and doing.

Table 1.1 Although leading, managing, and producing form a continuum, distinctions are drawn among them.

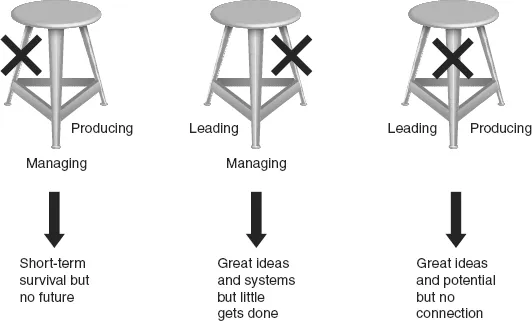

Figure 1.2 uses the metaphor of a three-legged stool to suggest how attention to the leading, managing, and producing functions produces a stable organization—one that cannot easily be “knocked over.” While an organization might temporarily survive balanced on two of the three legs, all three legs are needed for long-term survival. For example, an engineering consulting firm with only managing and producing legs may be precariously balanced. It believes that current success guarantees future success. It can be sailing along just fine. But, without leading, it fails to see the rocks versus the navigable waters ahead. Author Warren G. Bennis (1989) said, “Many an institution is very well-managed and very poorly-led. It may excel in the ability to handle each day all the routine inputs, yet may never ask whether the routine should be done at all.”

With only leading and managing functions, exciting visions and careful operating plans are left lying on the table. Little or nothing happens—or what does happen fails to meet expectations. Finally, when only leading and producing are present, the organization lacks translation between the vision and the producing functions. This is sometimes the last stage of an organization started by a talented entrepreneur who cannot give up control. He or she hires managers who are expected to be clones—and, therefore, for all practical purposes, they add very little value. The organization produces, but very poorly. The vision, admirable and wise as it may be, does not get translated into services or products.

The Traditional Pyramidal, Segregated Organizational Model

Assuming you agree that each organization has leading (deciding), managing (directing), and producing (doing) responsibilities, consider the manner in which these corporate responsibilities might be met. More specifically, consider the matter of individual responsibility in achieving the three corporate responsibilities.

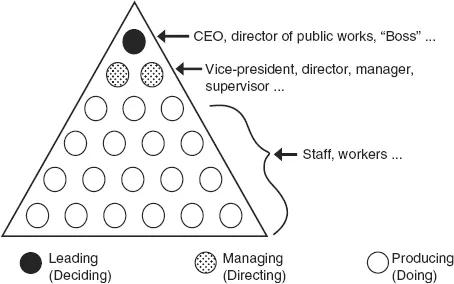

In what might be called the traditional pyramidal and segregated organizational model, as illustrated in Figure 1.3, the three functions reside in three separate groups of personnel. The vast majority of employees are the doers or producers, a distinctly different and much smaller group of managers are the directors, and one person, or perhaps a very small group, leads.

An aspiring and successful individual begins in a production mode and then passes serially or linearly maybe into managing and possibly into leading. Rather than being a trait that many can possess, albeit to different degrees, leading is considered the end of the line or ultimate destination for a very few. But is this the optimum way for an organization to meet its leading, managing, and producing possibilities? I don’t think so, although a command and control structure may be appropriate in certain situations.

The Shared Responsibility Organizational Model

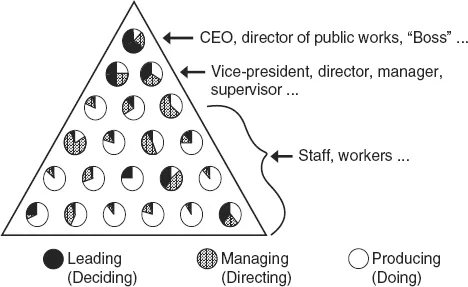

An organization will be stronger if what I previously referred to as the three organizational responsibilities now also become individual responsibilities. The goal should be to enable each member of the organization to be a decider, a director, and a doer as illustrated by Figure 1.4.

While the relative “amounts” of leading, managing, and producing will vary markedly among individuals in the organization, everyone should be enabled and expected to do all three in accordance with their individual characteristics. This shared responsibility organizational model, in contrast with the traditional segregated model, is much more likely to mine the organization’s gold, that is, extract and benefit from the diverse aspirations, talents, and KSAs that are typically present within an organization.

Because essentially all members are fully involved, the shared responsibility organization is more likely to synergistically build on internal strengths, cooperatively diminish internal weaknesses, and learn about and be prepared to respond to external threats and opportunities. Striving to enable everyone creates confidence, results, and pride. As noted by Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu, “But of a good leader, who talks little, when his work is done, his aim fulfilled, they will say, we did this ourselves.”

The Focus of This Book: Managing and Leading

The entry-level engineer or other technical person will, by definition, be well-prepared for and will spend a majority of his or her time producing, that is, carrying out the production function of the organization. An undergraduate education is typically a solid preparation for this function. The focus of this book is on managing and leading.

Your education may be preparing you, or may have prepared you, well for the managing and leading functions. For example, perhaps you are studying or have studied civil or environmental engineering in a department aligned with the Body of Knowledge (BOK) developed by the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE 2008), t...