Section Editors Paul D. Miller and Socrates E. Papapoulos

In March 2000, a National Institutes Consensus Development Conference redefined osteoporosis as “a skeletal disorder characterized by compromised bone strength predisposing to an increased risk of fracture. Bone strength reflects the integration of two main features: bone density and bone quality. Bone density is expressed as grams of mineral per area or volume and in any given individual is determined by peak bone mass and amount of bone loss. Bone quality refers to architecture, turnover, damage accumulation (e.g., microfractures), and mineralization. A fracture occurs when a failure-inducing force (e.g., trauma) is applied to osteoporotic bone. Thus, osteoporosis is a significant risk factor for fracture, and a distinction between risk factors that affect bone metabolism and risk factors for fracture must be made.”

In the intervening decade much has been learned about this very common disease, and the next 27 chapters provide details of all aspects of osteoporosis—etiology, diagnosis, management. A synopsis of those chapters is provided here.

Understanding of the epidemiology and pathogenesis of osteoporosis as detailed in Chapters 40 and 41 have advanced beyond the age-related decline in bone mass assessed by dual energy X-ray densitometry (DXA) and an assessment of fracture risk determined by the WHO-developed FRAX model to include invasive (bone biopsy) and noninvasive (high-resolution computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging) documentation of bone microarchitecture. It is now more clear that risk of fracture is heavily dependent on bone quality, possibly even more so than bone mass. Not to be forgotten in this emerging science is the contribution of falls to the likelihood of fracture occurrence. An osteoporosis-related fragility fracture is best defined as a fracture resulting from a fall from a standing height or less. The less bone mass, the more disrupted the bone microarchitecture, the greater the likelihood of sustaining a fracture (Chapter 40).

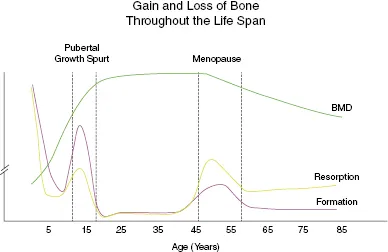

Not all fall-related fractures reflect osteoporosis, particularly in children. Figure 39.1 is a schematic of gain and loss of bone throughout life. Bone mass is low at birth and increases for the next 2 or 3 decades (it varies with the skeletal site being evaluated) before peak bone mass is acquired. Both bone formation and bone resorption are highest at birth, declining rapidly over the first few years of life. This is an age group where falls are not uncommon, either as the toddler is learning to stand and walk or as they grow and become involved in sporting activities. Advancing from a tricycle to a bicycle is a common cause of falls and fracture, but the high bone remodeling rate promotes rapid and complete healing in most children. The pubertal growth spurt results from a second surge of remodeling activity, but fractures are less common until engagement in more rigorous contact sports. In healthy people, peak bone mass and bone remodeling are stable unless a secondary cause of bone loss is present. In women, the decline in estrogen and/or the increase in gonadotropins at menopause (Chapters 43) result in a reversal of bone remodeling such that resorption now exceeds formation and bone mass decreases. Coincident with this is remodeling induced disruption of bone microarchitecture and most likely other as yet incompletely identified disturbances in skeletal integrity.

While osteoporosis is more prevalent after menopause, there are many factors that contribute to bone loss and osteoporosis with increased fracture risk in premenopausal women. In particular, anorexia, bulimia, and athletic amenorrhea interfere with the cyclical production of estrogen and progesterone (Chapter 43). Paradoxically, the alterations in menstrual function in patients with polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) do not have an adverse effect on bone mass. Bone mass may even be higher in patients with PCOS than in age-matched controls with normal menses—presumably related to the increased levels of androgens.

Age-related bone loss occurs in men but the mechanisms are not as well documented as they are in women. Age-related decline in testosterone and likely the change in diurnal excursion of testosterone as men age are important determinants of bone loss in men. There is also increasing data that links changes in fat mass (increase) and muscle mass (decrease) as major contributors to bone loss in women and men. The contributions of the sex hormones, sex-hormone binding proteins, gonadotrophins, and growth factors to gain and loss of bone in both men are elegantly described and detailed in Chapter 43.

Nutrition and lifestyle are critical factors in the development and maintenance of bone health (Chapters 42 and 47). Key nutritional factors are adequate intake of calcium and vitamin D. Guidelines for the optimal amount of calcium and vitamin D intake have recently been published by several major organizations but there is limited consistency in these guidelines. At issue is just “how much” or “how little” is regarded as adequate intake of calcium and vitamin D at different stages of life. It is possible to have inadequate intake of calcium, but dietary calcium overload is much less likely. Patients with calcium-containing kidney stones are often ill-advised to lower their calcium intake or do so of their own volition. Lowering dietary calcium is more likely to increase kidney stone risk as well as jeopardize skeletal health. Most recently, controversy has arisen about a possible link between excess calcium intake and the risk of coronary artery disease, but this issue remains unresolved. The issues regarding vitamin D are more complex. In particular there is a trend, at least in the United States, to measure 25- hydroxyvitamin D (25OHD) at annual physical examinations. Compared to the cost of the laboratory procedure, the cost of taking 1,000–2,000 units of vitamin D daily is substantially lower, with very limited likelihood of developing vitamin D toxicity. Patients with a history of malabsorption or overt malnutrition will benefit from regular monitoring of 25OHD, but this is a small fraction of the general population. As calcium intake has been linked to cardiovascular disease, there is a burgeoning literature linking 25OHD levels to diseases in seemingly every organ system and disease state. Hypothetically, this makes sense since the vitamin D receptor is present in many, perhaps most, tissues. However, to date the published data are inconsistent and inconclusive. In the 90 days before this chapter was written, there were 129 peer-reviewed publications listed in PubMed on the topic “diseases associated with vitamin D.” The chapters “Premenopausal Osteoporosis” (Chapter 63) and “Prevention of Falls” (Chapter 45) provide additional critical information about maintenance of skeletal health and integrity throughout life.

The bulk of the synopsis presented above relates to “primary” osteoporosis in which bone loss can be attributed to aging per se or the known hormonal consequences of aging such as the decline in estrogen and testosterone. “Secondary” osteoporosis refers to those conditions that do not start as a skeletal issue but reflect adverse consequences of the primary disease itself (e.g., celiac disease with associated malabsorption) and/or as a result of therapy (e.g., glucocorticoid) for many diseases. Diseases and therapies that adversely affect bone remodeling and bone mass or are associated with an increased risk of falling are detailed in Chapter 45.

Much has already been learned about the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying both primary and secondary osteoporosis and exciting new science is unraveling potential new factors in this scenario. This has resulted in the development of pharmacologic approaches to minimize further bone loss and to a great extent reverse the bone loss and decrease the likelihood of fracture. Chapters 48–53 describe the mechanism of action and the clinical use of therapies that have been documented to improve bone mineral density and reduce fracture risk and provide guidance into the appropriate use of these therapies for the several clinical scenarios described above. Each of these has demonstrated anti-fracture effec...