![]()

PART I

MATHEMATICS IN HISTORY

![]()

CHAPTER 1

THE ANCIENT ROOTS OF MATHEMATICS

Mathematics—the unshaken Foundation of Sciences, and the plentiful Fountain of Advantage to human affairs.

Isaac Barrow (1630-1677)

1.1 Introduction

Mathematics is a human enterprise, which means that it is part of history. It has been shaped by that history, and in turn has helped to shape it. In this chapter we will trace these connections.

Many societies have contributed to mathematics, but a main historical thread is discernible, one that has led directly to today’s mathematics. That thread began in the ancient Mediterranean world, swelled mightily in ancient Greece, dwindled at the time of the Roman empire, was kept alive and augmented in the Muslim world, re-entered Western Europe in the Renaissance, developed in Europe for several centuries, then spread throughout the world in the 20th century. We will spend most of our time on this thread, in part because so much is known about it, with a few excursions into other cultures.

Eurasia and Africa.1

Fingers, Knots, and Tally Sticks

Experiments have shown that humans, and other animals, are bom with innate mathematical abilities. They regularly distinguish between, say, one tree and two trees. The next logical step is counting, that is, establishing a one-to-one correspondence between sets of objects. This is no doubt also an ancient ability.

Once we can count objects, how do we communicate numbers to others? Most of what follows in this chapter is based on the historical, i.e., written record. But writing is a fairly recent invention. Before the written word, people used a variety of methods to represent numbers. Surely one of the first, and still important, methods was the use of various parts of the body. Some quite elaborate systems have been developed. The Torres Strait islanders, an indigenous Australian people, used fingers, toes, elbows, shoulders, knees, hips, wrists, and sternum to represent different numbers. Many languages preserve the remnants of such systems: the word for “five,” for example, is “hand” in Persian, Russian, and Sanskrit. And it is no coincidence that our number system is based on ten, the number of fingers.

Perhaps the most popular numbering system used notches on sticks or bones, so-called tally sticks, from the French word tailler, to cut. These date back at least 35,000 years, and must rank as one of the most successful technologies ever. As recently as 1826, tally sticks were used in official English tax records.

Another popular counting device was the stone. Our word “calculation” derives from the Latin calculus, which is a small stone. Early versions of the abacus were stones on the ground; “abacus” likely derives from the Hebrew abhaq, dust.

Knotted strings were a popular accounting tool throughout the world. The most notable examples of these were the amazing Incan quipu, which consisted of multiple knotted cords (up to 2000 of them) joined together.

A leading theory of the origin of writing in Mesopotamia, proposed by Denise Schmandt-Besserat, relates to a different method of recording numbers. It starts with the use of small clay tokens, found in archaeological sites, beginning circa 8000 BCE1. These tokens, in various standard shapes, were used for accounting: one shape might represent one sheep, for example, another one goat, or ten sheep. Imagine you are a merchant, and have hired someone to deliver a herd of 27 sheep to a neighboring city. The buyer needs to have some way to verify that the number of sheep that arrive is the same number sent. The solution was to encase tokens representing 27 sheep in a clay “envelope,” a hollow ball. The ball could be broken open at the destination, and the number of sheep verified.

Now imagine that the sheep’s journey has two legs; person A delivers them to person B, who in turn delivers them to the buyer. If B breaks open the ball to verify the count, what is the buyer to do? The solution found was to make impressions on the ball, using the tokens, before they were placed inside. After the clay ball hardened, these impressions could serve as a record as well as the tokens. Eventually, it was realized that the tokens were unnecessary. The “writing” on the ball sufficed.

Agriculture and Civilizations

Some time around 10,000 years ago, humans began developing agriculture, inaugurating the Neolithic, the “new stone age.” The first important crops were grains—large-seeded grasses—including wheat, sorghum, millet, and rice. Gradually, various animals were domesticated, notably cattle, sheep, oxen, pigs, and goats. This whole set of developments dramatically changed the way people lived. Instead of living in relatively small nomadic bands of “hunter-gatherers,” they started settling into villages. This allowed a larger population density.

In some areas of the world, usually in the flood plains of great river valleys, the agricultural settlements developed civilizations. Among these areas were Mesopotamia, the Nile in Egypt, the Yellow River in China, the Indus River in Pakistan, and the Ganges in India. Civilizations were characterized by more central organization, often including irrigation, granaries to store surplus grain, and cities.

The civilizations were based on the existence of agricultural surplus, which freed people to work on other things. This led to the development of many new technologies. Among these were the plow, wheeled vehicles, and, most notably, writing and metallurgy.

Civilizations required different, more sophisticated, types of mathematics. Geometry was needed for surveying land, building canals, dikes, and ditches, and constructing larger buildings like granaries and palaces. Administering the new city-states, apportioning taxes, and paying workers made increasing demands on arithmetic and algebra, as did the expanded commercial activity.

With the rise of civilization came new class structures. Most people were farmers, but some became blacksmiths, leather workers, engineers, architects, merchants, priests, scribes, surveyors, and of course kings. Some of the new, specialized professions (such as surveyors) nurtured their own mathematical techniques, handing them down through the generations. In some societies, small groups inside the new classes turned their collective attention to developing mathematics generally. Society provided practical inspiration for the new mathematics, but some mathematicians pursued knowledge for its own sake.

EXERCISES

1.1 What mathematics would a pre-agricultural (hunter-gatherer) society need?

1.2 What mathematics would an agricultural village need that a hunter-gatherer society would not?

1.3 What mathematics would a city need that a agricultural village would not?

1.4 Look up Incan quipus in your favorite Internet search engine. What did they look like? How were they used?

1.2 Ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt

The Middle East.1

Two of the earliest civilizations arose in the Near East.

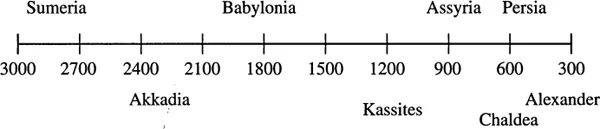

Ancient Mesopotamian history. All dates are BCE.

Mesopotamia (from the Greek, literally “between the rivers”) is the plain between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, about 600 miles long, in modern-day Iraq. Mesopotamia was home to the earliest known agriculture. The major crops were wheat and barley, but there were also fruits, including dates, grapes, figs, melons, and apples; vegetables, including eggplant, onions, radishes, beans, and lettuce; and sheep, cattle, goats, and pigs.

Figure 1.1 The Tigris and Euphrates rivers are above and to the left of center; the Nile is on the left.1

Between the Rivers

The farmers relied on the flooding of the Tigris and Euphrates. These floods, which could be violent and destructive, nonetheless left behind very fertile silt. Mesopotamia doesn’t get much rain, so the other important ingredient to agriculture was irrigation. One of the critical functions of the government was the construction and maintenance of irrigation systems. The first Mesopotamian civilization was the Sumerian, named after the city-state of Sumer in southern Mesopotamia. It arose circa 3500–3000 BCE. Politically, the early Sumerians did not have an empire; empires came later. Instead, they were organized into city-states, ruled by priest-kings. These city-states built up bureaucracies to manage the irrigation systems and the surplus grains. They even had postal systems. The Sumeria...