![]()

Part 1

The Respiratory Pathway, Lungs, Thoracic Wall and Diaphragm

The mouth

The mouth is made up of the vestibule and the mouth cavity, the former communicating with the latter through the aperture of the mouth.

The vestibule is formed by the lips and cheeks without, and by the gums and teeth within. An important feature is the opening of the parotid duct on a small papilla opposite the 2nd upper molar tooth. Normally the walls of the vestibule are kept together by the tone of the facial muscles; a characteristic feature of a facial (VII) nerve paralysis is that the cheek falls away from the teeth and gums, enabling food and drink to collect in, and dribble out of, the now patulous vestibule.

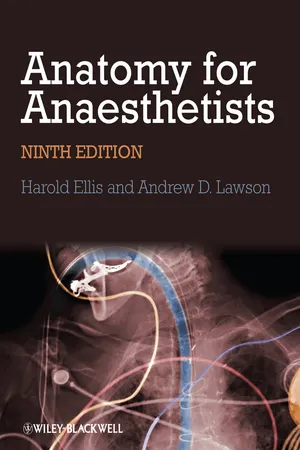

The mouth cavity (Fig. 1) is bounded by the alveolar arch of the maxilla and the mandible, and teeth in front, the hard and soft palate above, the anterior two-thirds of the tongue and the reflection of its mucosa forwards onto the mandible below, and the oropharyngeal isthmus behind.

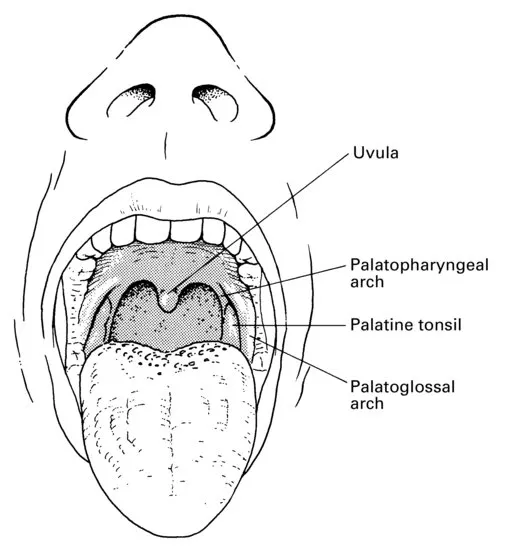

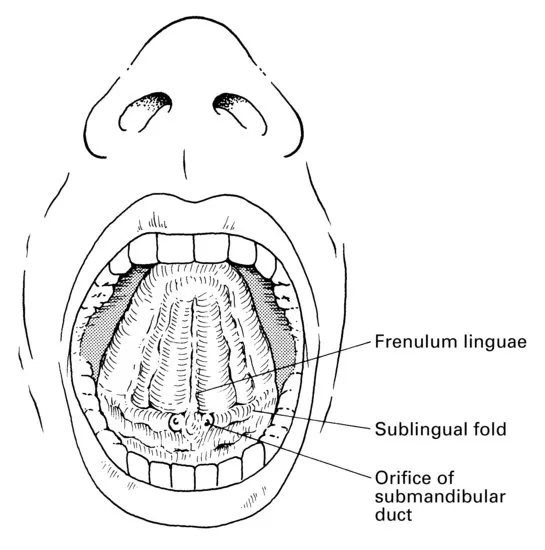

The mucosa of the floor of the mouth between the tongue and mandible bears the median frenulum linguae, on either side of which are the orifices of the submandibular salivary glands (Fig. 2). Backwards and outwards from these ducts extend the sublingual folds that cover the sublingual glands on each side (Fig. 3); the majority of the ducts of these glands open as a series of tiny orifices along the overlying fold, but some drain into the duct of the submandibular gland (Wharton's duct).

Inspect your mouth in a mirror. Elevate your tongue, then press on one or the other side onto your submandibular gland beneath the angle of the jaw. You will see a jet of saliva emerge from the orifice of the submandibular duct at the tip of the sublingual fold. While about it, pull your cheek laterally with a finger, press on your parotid gland on that side and observe a jet of saliva emerge from the parotid duct, which lies at the level of your 2nd upper molar tooth.

The palate

The hard palate is made up of the palatine processes of the maxillae and the horizontal plates of the palatine bones. The mucous membrane covering the hard palate is peculiar in that the stratified squamous mucosa is closely connected to the underlying periosteum, so that the two dissect away at operation as a single sheet termed the mucoperiosteum. This is thin in the midline, but thicker more laterally owing to the presence of numerous small palatine salivary glands, an uncommon but well-recognized site for the development of mixed salivary tumours.

The soft palate hangs like a curtain suspended from the posterior edge of the hard palate. Its free border bears the uvula centrally and blends on either side with the pharyngeal wall. The anterior aspect of this curtain faces the mouth cavity and is covered by a stratified squamous epithelium. The posterior aspect is part of the nasopharynx and is lined by a ciliated columnar epithelium under which is a thick stratum of mucous and serous glands embedded in lymphoid tissue.

The ‘skeleton’ of the soft palate is a tough fibrous sheet termed the palatine aponeurosis, which is attached to the posterior edge of the hard palate. The aponeurosis is continuous on each side with the tendon of tensor palati and may, in fact, represent an expansion of this tendon.

The muscles of the soft palate are five in number: the tensor palati, the levator palati, the palatoglossus, the palatopharyngeus and the musculus uvulae (see Fig. 13).

The tensor palati arises from the scaphoid fossa at the root of the medial pterygoid plate, from the lateral side of the Eustachian cartilage and the medial side of the spine of the sphenoid. Its fibres descend laterally to the superior constrictor and the medial pterygoid plate to end in a tendon that pierces the pharynx then loops medially around the hook of the hamulus to be inserted into the palatine aponeurosis. Its action is to tighten and flatten the soft palate.

The levator palati arises from the undersurface of the petrous temporal bone and from the medial side of the Eustachian tube, enters the upper surface of the soft palate and meets its fellow of the opposite side. It elevates the soft palate.

The palatoglossus arises in the soft palate, descends in the palatoglossal fold and blends with the side of the tongue. It approximates the palatoglossal folds.

The palatopharyngeus descends from the soft palate in the palatopharyngeal fold to merge into the side wall of the pharynx: some fibres become inserted along the posterior border of the thyroid cartilage. It approximates the palatopharyngeal folds.

The musculus uvulae takes origin from the palatine aponeurosis at the posterior nasal spine of the palatine bone and is inserted into the uvula. Injury to the cranial root of the accessory nerve, which supplies this muscle via the vagus nerve, results in the uvula becoming drawn across and upwards towards the opposite side.

The tensor palati is innervated by the mandibular branch of the trigeminal nerve via the otic ganglion (see page 274). The other palatine muscles are supplied by the pharyngeal plexus of the vagus nerve, which transmits cranial fibres of the accessory nerve via the vagus.

The palatine muscles help to close off the nasopharynx from the mouth in deglutition and phonation. In this, they are aided by contraction of the upper part of the superior constrictor, which produces a transverse ridge on the back and side walls of the pharynx at the level of the 2nd cervical vertebra termed the ridge of Passavant.

Paralysis of the palatine muscles results (just as surely as a severe degree of cleft palate deformity) in a typical nasal speech and in regurgitation of food through the nose.

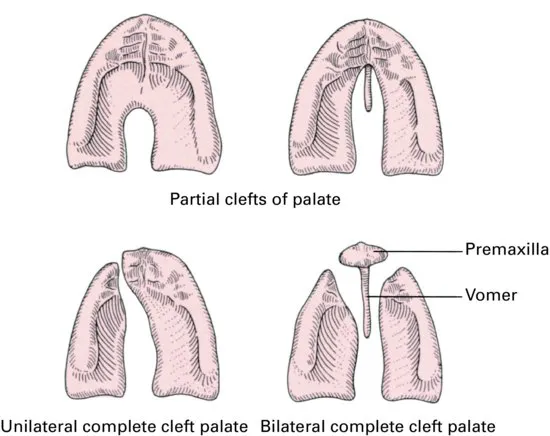

Cleft palate

The palate develops from a central premaxilla and a pair of lateral maxillary processes: the former usually bears all four (occasionally only two) of the incisor teeth. All degrees of failure of fusion of these three processes may take place. There may be a complete cleft, which passes to one or both sides of the premaxilla; in the latter case, the premaxilla prolapses forwards to produce a marked deformity. Partial clefts of the posterior palate may involve the uvula only (bifid uvula), involve the soft palate or encroach into the posterior part of the hard palate (Fig. 4).

The nose

The nose is divided anatomically into the external nose and the nasal cavity.

The external nose is formed by an upper framework of bone (made up of the nasal bones, the nasal part of the frontal bones and the frontal processes of the maxillae), a series of cartilages in the lower part, and a small zone of fibrofatty tissue that forms the lateral margin of the nostril (the ala). The cartilage of the nasal septum constitutes the central support of this framework.

The cavity of the nose is subdivided by the nasal septum into two quite separate compartments that open to the exterior by the nares and into the nasopharynx by the posterior nasal apertures or choanae. Immediately within the nares is a small dilatation, the vestibule, which is lined in its lower part by stiff straight hairs.

Each side of the nose presents a roof, a floor and a medial and lateral wall.

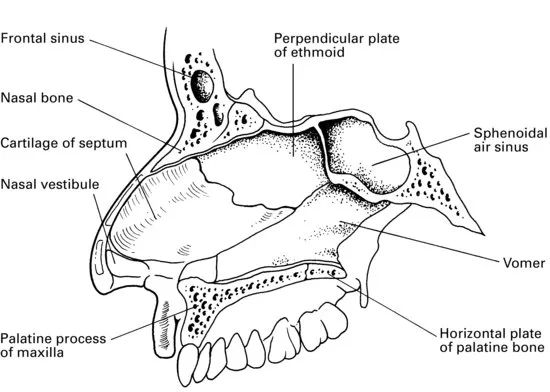

The roof first slopes upwards and backwards to form the bridge of the nose (the nasal and frontal bones), then has a horizontal part (the cribriform plate of the ethmoid), and finally a downward-sloping segment (the body of the sphenoid).

The floor is concave from side to side and slightly so from before backwards. It is formed by the palatine process of the maxilla and the horizontal plate of the palatine bone.

enlrg 12pt? The medial wall (Fig. 5) is the nasal septum, formed by the septal cartilage, the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid and the vomer. Deviations of the septum are very common; in fact, they are present to some degree in about 75% of the adult population. Probably nearly all are traumatic in origin, and result from quite minor injuries in childhood or even at birth. The deformity does not usually manifest itself until the second dentition appears, when rapid growth in the region produces deflections from what had been an unrecognized minor dislocation of the septal cartilage. Males are more commonly affected than females, a distribution which would favour this traumatic theory. Both nostrils may become blocked, either from a sigmoid deformity of the cartilage or from compensatory hypertrophy of the conchae on the opposite side. The deviation is nearly always confined to the anterior part of the septum.

The lateral wall (Fig. 6) has a bony framework made up principally of the nasal aspect of the ethmoidal labyrinth above, the nasal surface of the maxilla below and in front, and the pe...