![]()

Chapter One

Sequence

Time is nature's way of keeping everything from happening at once.

—John Wheeler1

Picture yourself pouring water through a funnel. If all the water tried to escape the small end of the funnel at the same time, the result would be chaos, like a crush of people trying to exit a movie theater after someone yells “Fire!” A funnel works because gravity and other forces gently encourage the water molecules to get in line, a line that becomes a fast-moving spiral. When we look at a funnel we see its shape, and we understand its function. What we don't think about is the underlying, and often invisible, timing mechanism that makes it work: sequence.

In business, as in life more generally, we control and manipulate most easily what we can see and touch: we replace one technology with another; we redesign the packaging of our products. Sequences, in contrast, are abstract and intangible, and they are therefore easy to miss. But it is important to find them. Modify a sequence—produce a product before the demand is apparent, as opposed to after—and your risk and opportunity profile looks very different. Modify or redescribe a sequence, and it can change how a product is perceived, which can affect its sales. Is the secondhand Jaguar you are about to buy “pre-owned”—owned by someone else before you purchased it, or “used”—purchased after someone else has driven it?

Finding or noting the presence of a sequence can be the key to deciding when to act. For example, knowing the steps a country needs to go through to produce a nuclear weapon is critical in determining when, if ever, you should take steps to prevent it. That's why we need to train our eyes to look for the sequences in our environment; they provide clues about timing. They can also help us understand why something is delayed. For example, if there is no clear sequence of steps allowing a country to exit the EU without putting itself (and the remaining countries) at risk, then expect a decision to start down that path to be postponed—perhaps indefinitely.

The Characteristics of Sequences

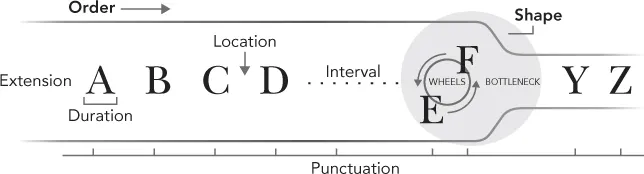

When you find a series of events that form a sequence, like the water molecules exiting a funnel, zoom in and look more closely. Sequences are not just about what follows what. Sequences have a number of important characteristics, which I describe in this section.

1. Order. What follows what, and why? Is there some reason why A is followed by B, and B by C? Is this order required? Would it be better to do something in a different order?

2. Punctuation. Are there recognizable steps or stages? Can one be skipped, and can you come (loop) back and finish it later?

3. Interval and duration. How long will each step or stage take, and how much time will elapse between steps?

4. Shape. Will there be bottlenecks or other shapes (I'll describe one in a moment) that will make progress slow or difficult?

5. Location. A sequence defines a series of locations. Does an event occur early in a sequence, in the middle, or perhaps at the end, and does its location matter?

6. Extension. How long is the sequence? When does it begin and end?

Take a moment to find some of these characteristics, illustrated in Figure 1.1, a close-up view of a sequence.

Let's move on and consider each characteristic in more detail.

Order

The order in which an event or action occurs is the primary property of any sequence. A is followed by B, B by C, and so on.

In creating a new flavor of coffee, you would take certain steps before announcing the product: agree on the formula, name the flavor, market-test the taste, iterate the ingredients to adjust the taste, market-test again, and so on. Once you observe or identify a particular order in your activities, such as the one in this coffee example, the next question to ask is whether it can be changed. Could one step come before another, or could two steps be inverted? And would a change in order benefit your business? Suppose you waited to name the coffee flavor until after the market test, for example—would that change how customers react? Or could a step be omitted? What if you omitted the second market test—how might that impact your budget? Everything we do has a particular order. Sometimes it is useful to pause and consider alternatives, particularly if you have been doing things in the same order for years.

When the order of a sequence can't be changed (one step must follow another, and no step can be skipped), it can cause problems. Let's use the launch of Dean Kamen's Segway as an example that illustrates what I call strict serial constraints.

You may have seen someone riding the original Segway PT (personal transporter) when the machine was first introduced in 2001. At the time, it probably looked like it would tip over, passenger and all. But that didn't happen because the Segway is self-balancing—that's what makes it breakthrough. Still, you would be skeptical about safety and ease until you rode one for yourself. So, with that in mind, when would you buy one? Probably not until you had a test ride. And when is that? Not until distributors carried it. But distributors didn't carry it for quite some time because laws in most states prohibited the use of Segways on sidewalks. Therefore, you wouldn't have been able to purchase a Segway until state laws were changed. The company lost five-plus years of sales because it introduced the product before it could be widely used.

Segway found itself caught in a vicious cycle: distributors wouldn't carry its product until they knew there was a market, but they couldn't know about the market until customers tried the product, and customers couldn't try it because distributors didn't carry it. Due to its revolutionary nature, the Segway was developed in secret, which meant that work on downstream tasks, such as lobbying municipalities to allow the device to be used on sidewalks, could not start until the product was unveiled. Did the Segway's developers identify possible routes to faster state approval or decide on a later launch? Did they anticipate the vicious cycle involving distributors? I don't know the answers to these questions, but in a certain sense, for our purposes, they are immaterial. What matters is that you learn to ask sequence-related questions in your own business so that you can better anticipate the difficulties you might encounter.

Notice in the case of the Segway that all of the timing risks related to order could have been identified at the outset if someone had been looking. But the company's timing strategy appears to have been typical: the focus was on speed, getting the product to market as soon as possible. The theme of this book is that there is a lot more you can see if you know how and where to look.

Like Dean Kamen, Saul Griffith needed to recognize the steps needed to make his invention successful. In 2004, when Griffith was a PhD student at MIT, he invented a way to custom manufacture low-cost eyeglasses for people in the developing world.2 The problem, as he understood it then, was manufacturing lenses without having to build an expensive factory, which poor countries couldn't afford. Griffith's solution was a technology to shape a fast-drying liquid into any lens.

Technically, his invention was a great success. He received a $30,000 award from MIT and a $500,000 “genius grant” from the MacArthur Foundation. Unfortunately, Griffith didn't have a timing lens in his tool kit, one that would help him see the sequence on which the success of his invention depended.

As Griffith put it, “The real problem with eyeglasses in the developing world isn't making lenses . . . it's testing eyes and writing prescriptions for people with little or no access to medical care—a matter of politics and economics rather than technology.”3 He missed the steps individuals needed to take before they could use his technology; as a result, his invention never found a market. But Griffith also misdiagnosed the problem. He saw it as one of politics and economics, which it undoubtedly was. But it was also a sequence problem.

Sequences, of course, have other characteristics besides order that are relevant in business. I'll mention them briefly, as they will be covered in greater detail in later chapters.

Punctuation

Sequences use steps and stages as a way to break a continuous process into parts in the same way commas and semicolons divide a sentence, and additional white space separates paragraphs. Usually, we think of condensing a process and eliminating steps as a time-saving perk for customers using products. But eliminating steps and inserting a period sooner is not always the answer. For instance, a freeze-dried egg could have easily been included as part of the ingredients in pancake mix. All a consumer would have to do, then, was add water, mix, and cook. But manufacturers believed that women at the time would feel guilty about a process so simple and devoid of fresh ingredients—so they added the extra step of asking women to add the egg themselves.

It is not always possible to skip to the end without inserting a pause or another punctuation mark. In the first Gulf War, for example, allied troops rushed to Baghdad, detouring around a number of smaller cities on route. This allowed them to reach the capital sooner, but it meant that they had to go back later to deal with security issues that had grown more serious in the interim. When there is an emphasis on speed, be prepared for skipped steps and the timing issues they raise. Ask yourself: When will a return be possible, and what will I find when I get there?

Skipping ahead can even be illegal, as in “front-running” in finance. Front-running occurs when a trader receives an order from an investor to buy a stock and the trader steps in ahead of that order, which he knows will raise the price of the stock, to buy it for the house account. He then sells what he has bought to the investor at the higher price and locks in a profit.

If you don't take all the steps in a sequence into account, you can make an error. As an example, let's take something that is fundamental to any business: the price of a commodity on which the business depends. Increase the supply of this commodity, and the price should fall. Increase demand, and the price should rise. But things are not so simple in the real world. The price of natural gas, for example, will not to rise or fall based on how much is produced and the overall level of demand, because natural gas does not go directly from well to consumer. There is an intermediate step. Natural gas can be stored. When storage capacity rises, excess supply can be kept off the market until prices recover. If you forget about this step in the sequence, like the omission of a comma or period that makes a sentence difficult to read, you will not understand why an abundance of natural gas (what is coming out of the well) does not always result in lower prices for consumers.

Interval and Duration

When we look at a sequence, we need to notice how much time elapses between steps (interval) and how long each step or stage takes (duration).

After a start-up company receives financing, for example, investors prefer profitability to happen sooner rather than later—they want the shortest possible time between these two steps. There are many instances when a short interval between steps or stages is preferable. In fall 2010, for example, European regulators met to consider reducing the time between when a transaction is completed and when securities are exchanged for cash. A shorter interval would reduce the risk that an unexpected event, like a default, might occur in the interim.

We customarily divide the week...